For centuries, Catholics have flocked to the Italian city of Turin to be in the presence of its famous Shroud.

The venerated piece of linen, measuring 14 feet 5 inches by 3 feet 7 inches, has a faint image of the front and back of a man, interpreted by many as Jesus Christ.

Believers say it was used to wrap the body of Christ after his crucifixion, leaving its bloody imprint, like a photographic snapshot.

Despite repeated claims of a “hoax”, a scientist is now convinced the object actually engulfed Jesus and says there is an “enormous amount of evidence” to prove it.

Professor Liberato De Caro, a committed Catholic and deacon in his local church, debunked claims that it occurred in medieval times with his recent study.

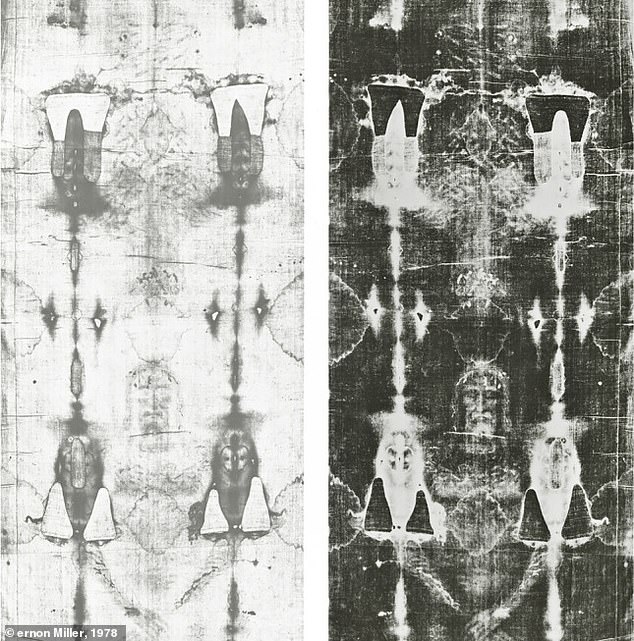

The Shroud of Turin presents the image of a man with sunken eyes, which experts have analyzed under different filters to study it (in the photo)

Professor De Caro told the Telegraph: ‘If I had to be a judge in a trial, weighing all the evidence that says the Shroud is authentic and the little evidence that says it is not, I could not calmly declare that the Shroud of Turin is medieval.

“It would not be correct, given the enormous amount of evidence in its favor.”

Professor De Caro recent radiological study The finds of the Shroud of Turin date back to 2,000 years ago, approximately when Christ lived and died.

We also know from the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP) in the 1970s and 1980s that the holy cloth was indeed stained with blood.

STURP found that the spots have traces of hemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells that supplies oxygen.

The stains also tested positive for serum albumin, the most abundant protein in human blood plasma.

In 1981, in its final report, the STURP wrote: ‘We can conclude for now that the image on the Shroud is that of a real human form of a scourged and crucified man.

“It’s not the product of an artist.”

So until their new study, “the only missing piece of the puzzle was the citations,” Professor De Caro told MailOnline.

He said everything that appears on the Shroud is “highly correlated with what the Gospels tell about Jesus Christ” and his death.

The cloth appears to display faint brown images on the front and back, depicting an emaciated man with sunken eyes who stood between 5 feet 7 and 6 feet tall.

The marks on the body also correspond to Jesus’ crucifixion wounds mentioned in the Bible, including thorn marks on the head, lacerations on the back, and bruises on the shoulders.

Historians have suggested that the cross he carried on his shoulders weighed around 300 pounds, which would have left bruises.

The Bible states that Jesus was scourged by the Romans, matching the lacerations on his back, who also placed a crown of thorns on his head before the crucifixion.

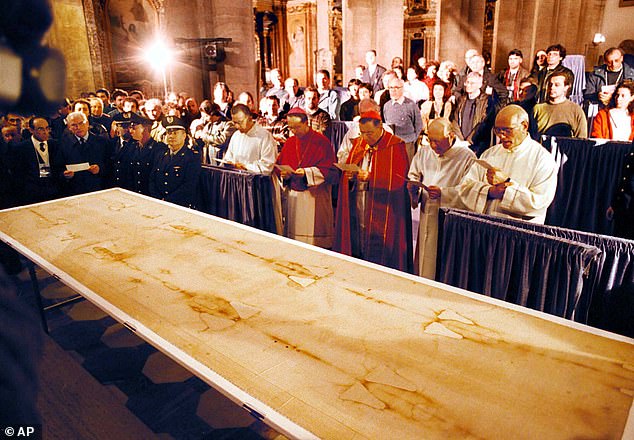

The Shroud first appeared in 1354 in France. After initially denouncing it as fake, the Catholic Church has now accepted the shroud as genuine. In the photo, Pope Francis visits the Shroud of Tourin in 2015

The Shroud of Turin (pictured) is believed by many to be the cloth in which Jesus’ body was wrapped after his death, but not all experts are convinced it is genuine.

Research in the 1980s appeared to debunk the idea that it was real after dating it to the Middle Ages, hundreds of years after the death of Christ, suggesting it was an elaborate medieval hoax.

But Italian academics used a new technique involving X-rays to date the material and confirmed that it was made in the time of Jesus, about 2,000 years ago.

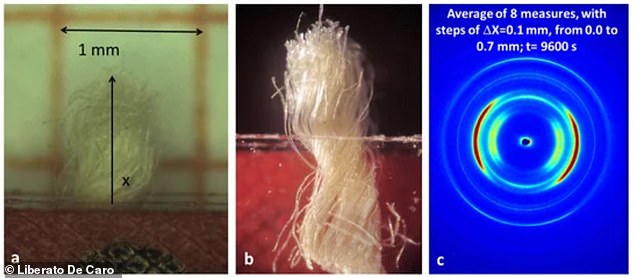

Professor De Caro and his team at the Institute of Crystallography in Bari, Italy, used a technique called wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) on a small sample of the shroud, smaller than a grain of rice.

WAXS can date ancient linen threads by “inspecting their structural degradation” at a microscopic level.

The Bible says that Joseph of Arimathea wrapped Jesus’ body in a linen shroud and placed it in a tomb.

Scientists obtained small samples of the Shroud of Turin (left) and exposed them to wide-angle X-ray radiation to create an image of the linen sample (right) that was used for dating.

Part of the analysis examined the flax’s cellulose patterns, the long chains of sugar molecules linked together.

These sugar molecules break down over time, showing how long a garment or fabric has been around.

Based on the amount of breakage, the team determined that the shroud was kept at temperatures of about 72.5°F and a relative humidity of about 55 percent for 13 centuries before reaching Europe.

If it had been preserved in different conditions, the aging would be different.

The researchers then compared the decomposition of cellulose in the Shroud to other linens found in Israel dating back to the 1st century.

They concluded that the structural degradations were “fully compatible” with those of the other linen sample, dated, according to historical records, between 55 and 74 AD.

The team also compared the Shroud to samples of bedding made between 1260 and 1390 AD and found no matches.

Some suggest that the blood stains on the shroud (shown in this negative image) are clear evidence that the cloth was used to wrap a wounded person.

The new findings lend credence to the idea that Jesus’ corpse left the faint, blood-stained pattern of a man with his arms crossed in front.

They also contradict findings from the 1980s that the shroud does not date anywhere near the time of Jesus.

At that time, researchers analyzed a small piece of the shroud using carbon dating and determined that the cloth appeared to have been made sometime between 1260 and 1390, during the medieval period.

However, the authors of the new study say that carbon dating would not have been reliable because the fabric has been exposed over the centuries to contamination that cannot be removed.

Furthermore, there is no way to explain how it could have been forged with medieval technology.

“Although authenticity cannot be established, it should be fairly easy to determine whether it is a medieval forgery,” said Tim Andersen, a research scientist at the Georgia Institute of Technology who was not involved in the new study.

‘However, despite decades of scientific evidence and peer-reviewed articles on the matter, that conclusion has never been proven.

“Rather, testing has continually led us away from any known forging techniques.”