Josh Hammer is the syndicated host of ‘The Josh Hammer Show’ and senior editor at large for Newsweek.

Democrats’ worst fears have finally come true.

They are being forced to win the 2024 elections at the polls, not in the courts.

Oh how horrible!

“Ultimately, it will be up to American voters to save our democracy in November,” Colorado Democratic Secretary of State Jena Griswold despaired Monday, just hours after the Supreme Court unanimously rejected her wild plan to oust Trump. from the state ballot.

“I believe that under our Constitution, states should be able to prohibit insurrectionists from breaking their oaths,” he complained.

Too bad nine judges – appointed by Republicans and Democrats – did not agree. They concluded that a ‘mosaic’ system of 50 political appointees unilaterally choosing who Americans can and cannot vote for would be an undemocratic abomination.

But the Democrats and their anti-Trump cronies were never going to let common sense get in the way of a good time.

Remember when conservative lawyer turned CNN green room squatter George Conway confidently predicted that Trump had no chance at the Supreme Court?

“He lost, it’s over,” Conway huffed at a panel of experts in December.

Or how about former J. Michael Luttig, the once-respected Fourth Circuit judge who recently developed a debilitating case of Trump derangement syndrome?

“Ultimately, it will be up to American voters to save our democracy in November,” Colorado Democratic Secretary of State Jena Griswold despaired Monday, just hours after the Supreme Court unanimously rejected her wild plan to oust Trump. of the state vote. .

Democrats’ worst fears have finally come true. They are being forced to win the 2024 elections at the polls, not in the courts. Oh how horrible!

‘(The) decision of the Colorado Supreme Court was masterful. “It was brilliant and it is an unquestionable interpretation of the 14th Amendment,” he growled in defense of Griswold’s plot.

So “impregnable” that it failed to obtain a single vote in the Supreme Court?

Your Honor, let the record show that you are more legally deranged than Judge Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson.

Take a bow!

Today, listening to the lunatic left was like watching the liberal body politic struggle through five abbreviated stages of grief.

There was denial.

Democrat Jamie Raskin has vowed to “revive legislation” to ban Trump from office. (Didn’t you already try it once?)

There was anger.

Keith Olbermann, always unhinged, opined that the High Court “betrayed democracy” and should be “dissolved.” (You have to destroy democracy to save it!)

There was acceptance.

“I know it’s probably the right decision,” Whoopi Goldberg admitted on ‘The View,’ “but I don’t like that we’ve normalized this man.”

Of course, that’s what this is all about. The left believes that only they can defeat Trump, and by any means necessary, whether through the courts, state governments, Russian collusion investigations, or Pink Pussy Hat marches.

But to date, all efforts, whether legally justified or not, have completely and utterly failed.

Trump’s federal prosecution for alleged mishandling of classified documents at Mar-A-Lago is stalled.

A special counsel investigation into the former president’s behavior on Jan. 6 was delayed beyond the November election.

“I believe that under our Constitution, states should be able to prohibit insurrectionists from breaking their oaths,” complained Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold (above). She is sorry that nine judges – appointed by Republicans and Democrats – did not agree.

Remember when conservative lawyer turned CNN green room squatter George Conway confidently predicted that Trump had no chance at the Supreme Court? “He Lost, it’s over,” Conway huffed at a panel of experts in December.

And in Fulton County, Georgia, the blatant corruption of far-left District Attorney Fani Willis has derailed her election interference case.

Other lawsuits may have hurt Trump financially, but politically they have only helped him by providing rocket fuel to his campaign.

Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg’s indictment of Trump for alleged hush money payments to Stormy Daniels coincides perfectly with the date when Trump’s popularity in the Republican primaries began to skyrocket.

Now, with these ballot ban tricks in Colorado, Maine, Illinois and other places declared dead on arrival, Democrats must accept the fact that they will have to win a real election. And for them, that’s a terrifying prospect.

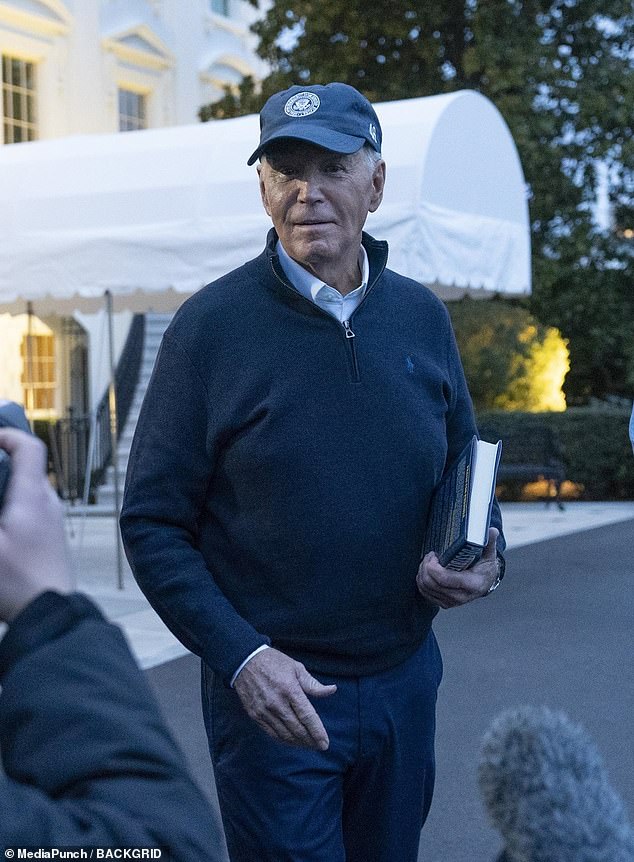

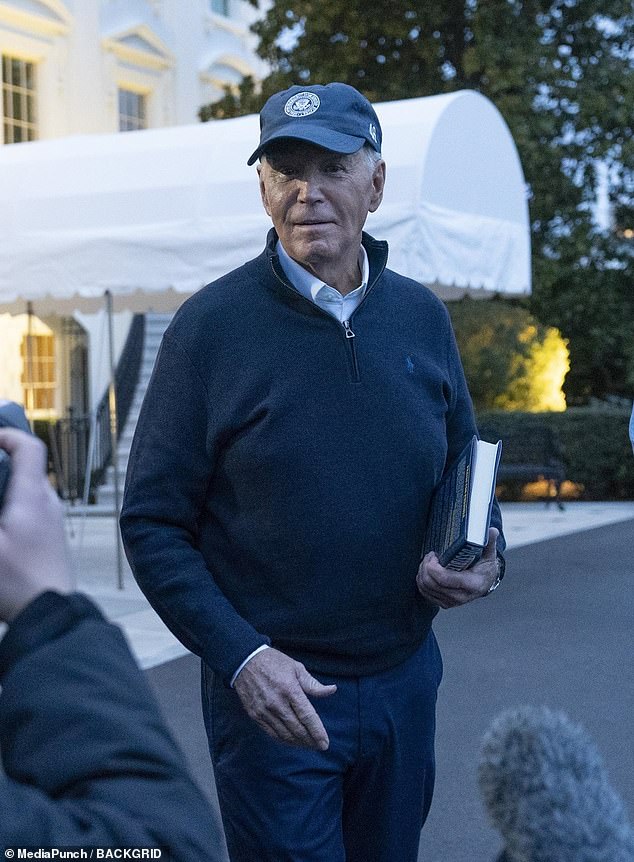

Currently, their octogenarian candidate is losing badly to Trump.

A new Bloomberg/Morning Consult poll showed that Trump is now beating Uncle Joe in all the major swing states: Pennsylvania, Nevada, Wisconsin, Georgia, Arizona, North Carolina and Michigan.

This week’s New York Times/Siena College poll gave Trump a five-point lead over the president Orthopedic Shoes. Three out of four voters think the country is headed in the wrong direction. And more than twice as many people say Biden’s policies have hurt them than believe they have helped them.

Perhaps most surprising of all, a whopping 73 percent of registered voters say Biden is “simply too old to be an effective president.”

I’m no ‘George Conway’, but this seems wrong to you.

Keith Olbermann, always unhinged, opined that the High Court “betrayed democracy” and should be “dissolved.” (You have to destroy democracy to save it!)

In the Democratic primary held in Michigan last week, 100,000 voters voted for “uncommitted” instead of their party’s incumbent president. Meanwhile, Nikki Haley scored her first victory in the Washington DC Republican primary this week.

Only 2,000 people showed up to vote. That tells you everything you need to know.

The Trump train is moving towards the Republican nomination… and Biden is limping.

Yes, the Democrats are in full crisis.

Therefore, they and their media can be expected to continue to undermine democracy.

Joe, who bravely left the White House hospice to give a softball interview to The New Yorker, now claims that Trump will not accept the results of the 2024 election.

It is a threat to democracy!

Well, what else do they have?

Biden can barely complete a sentence, let alone work the stump. Americans can expect another basement housing campaign, just like the one we had in the dark days of the 2020 COVID election.

There is nothing more “undemocratic” than that.