The true face of an ancient Egyptian mummy who died screaming in agony will be seen for the first time in 3,500 years after scientists reconstructed its image.

Known as the Screaming Woman, the mummy was found in 1935 in Deir Elbahari, Egypt, in the family tomb of royal architect Senmut.

Unusually for a mummy, her organs were left inside her, leading to a long belief that her mouth was left open by careless embalmers.

But after a recent study revealed that an agonizing death was to blame for his deformed expression, scientists decided to reconstruct his face in life.

Cicero Moraes, the Brazilian graphics expert responsible for the reconstruction, said the end result was a “pleasant face” achieved by combining several approaches.

The true face of an ancient Egyptian mummy who died screaming in agony can be seen for the first time in 3,500 years, after scientists reconstructed its image.

The mummy was found in 1935 at Deir Elbahari, Egypt, in the family tomb of the royal architect, Senmut.

He said: ‘I used a technique that combines elements of traditional schools of facial reconstruction with new approaches based on data from CT scans of living people.

‘These projections allow us to discover the spatial limits of structures such as the ear, eyes, nose, mouth and the like.

‘In addition, some structures are also drawn in profile, such as the nose and the lateral face.

‘The data is complemented by the anatomical deformation technique, where the head of a virtual digital donor is adjusted to the skull to be approximated.

‘There is usually compatibility between all the data, with minor differences, so the final face is an interpolation of all the information.’

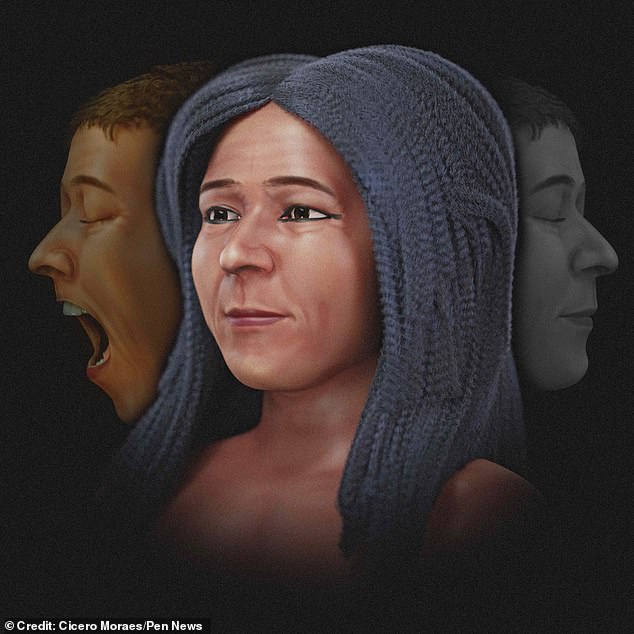

Mr. Moraes created several versions of the face.

One is objective, with eyes closed and in grayscale to avoid making judgments about skin tone or eye color.

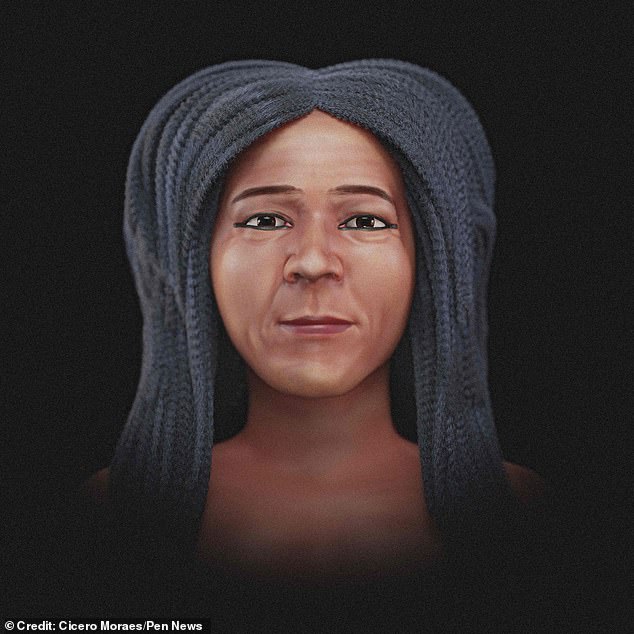

Another is more subjective and shows the woman as she might have looked in life, in color and with the wig she was buried in.

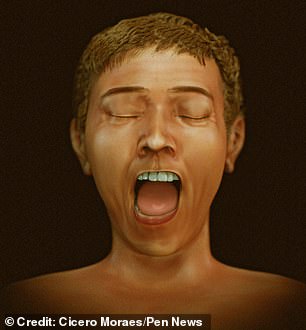

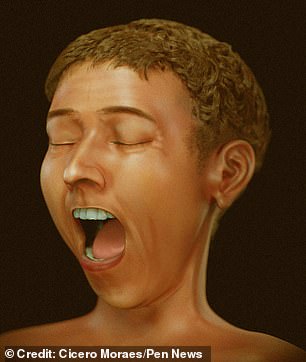

Moraes created several versions of the face. One is objective, with eyes closed and in grayscale to avoid making judgments about skin tone or eye color (right). Another is more subjective, showing the woman as she might have looked in life, in color, with the wig she was buried in (center). And a third captures her scream, revealing what she might have looked like when she was first buried (left).

CT scans estimated that he was approximately 48 years old at the time of his death and had suffered from mild arthritis in his spine.

And a third captures her scream, revealing what she might have looked like when she was first buried.

Mr Moraes knows his choice of skin tone could prove controversial in later performances.

He said: ‘The question of the skin colour of the ancient Egyptian people is a source of much controversy, and the debate moves from the scientific to the cultural and political realm.

‘To avoid these problems, I have sought an approach based on publications on the subject, data collected from studies of local groups and ancient Egyptian art.’

Sahar Saleem of Cairo University, lead author of the recent Screaming Woman study, attributed the mummy’s expression of pain to a cadaveric spasm.

“She was embalmed with expensive imported embalming material,” said Dr. Saleem.

‘This, and the well-preserved appearance of the mummy, contradicts the traditional belief that the failure to remove its internal organs meant poor mummification.’

He continued: ‘The screaming facial expression of the mummy in this study could be read as a cadaveric spasm, implying that the woman died screaming in agony or pain.

Cicero Moraes, the Brazilian graphics expert behind the reconstruction, said the end result was a “pleasant face” achieved by combining several approaches.

Mr Moraes said: “I used a technique that combines elements of traditional schools of facial reconstruction with new approaches based on CT scan data from living people.”

‘This mummified Screaming Woman is a true ‘time capsule’ of the way she died, revealing some of the secrets of mummification.’

However, the cause of his painful death has been lost to history.

Using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy on the remains, Dr. Saleem and her colleagues revealed that the body was embalmed with juniper and frankincense.

These were expensive, the former being imported from the eastern Mediterranean and the latter from East Africa or southern Arabia.

The mummy also wore a wig made from date palm fibers, which were treated with quartz, magnetite and albite crystals.

This was probably to stiffen the locks and turn them black, a colour the ancient Egyptians believed represented youth, Dr Saleem said.

His remains were discovered in the tomb of Senmut in Deir Elbahari, alongside the remains of his parents.

The woman’s coffin did not identify her by name, but her burial site near the mortuary temple of the great pharaoh Hatshepsut offers a clue.

He added: ‘The excavation notes mentioned that she was wearing two rings with jasper scarabs set in gold and silver respectively.

‘The material used for these amulets and jewelry denotes the wealth and socioeconomic status of the person.’

The woman’s coffin does not identify her by name, but her burial place near the mortuary temple of the great pharaoh Hatshepsut offers a clue.

She was buried next to the parents of Senmut, supervisor of royal works and architect of the temple, who is said to have been the pharaoh’s lover.

“She was likely a close relative of Senmut and shared the final resting place of his parents,” said Dr Saleem.

Mr Moraes praised Dr Saleem and her co-author, Samia El-Merghani, of Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, for their “inspiring” work.

He said: ‘I really enjoy two things: reading scientific papers and writing them.

‘I had the opportunity to read the article published by Saleem & El-Merghani, who provided the detailed data of the discovery, under a Creative Commons license.

‘I decided to do my part by putting a face to the discovery.’

Mr. Moraes published his study in the magazine OrtogOnLineMag.