As I walked to the station in the rain yesterday morning, a young woman approached me on the sidewalk, clutching an umbrella in one hand and looking at the smartphone she was holding in the other.

Not looking where he was going, he hit mine with his umbrella and almost knocked it out of my hand. I blurted out the word that most naturally comes to the lips of many of us in circumstances like these.

‘I’m sorry!’ I said.

After getting my apologies for his carelessness, he gave me a dirty look and continued walking.

Ah, well, one gets used to this kind of treatment after spending one’s life apologizing for sins one hasn’t committed. Stepping on my foot on the subway? “I’m sorry,” I say, wincing. Elbowing me aside in line for the bus? “I’m sorry,” again.

Look at Tony Blair, who was happy to apologise for Britain’s failure to alleviate the Irish potato famine, 150 years after the event.

When a young woman accidentally hit me with her umbrella while she was glued to her phone, I might have expressed my feelings more honestly by saying, “Watch where you’re walking, you idiot!”

‘I’m so sorry, but we ordered our food 50 minutes ago and there’s still no sign of it’; ‘I’m sorry, but you said you’d come yesterday to fix our leaky pipe’.

I apologize to the dog when I bump into him, and I have even been known to apologize to inanimate objects when I bump into them on the street.

This week, a survey of 1,000 adults confirms that many others simply believe it is untrue that the hardest word to say is “I’m sorry”. Researchers, commissioned by Honor for the launch of its new mobile phone, found that the average Briton apologises around three times a week (or around 150 times a year), while 38 per cent of us admit to saying sorry when we don’t really mean it.

Of course, some people apologize for others’ mistakes as a sarcastic expression of passive aggression. In my experience, this is particularly true during marital fights.

—Oh, I’m so sorry, honey. I should have reminded you that I wouldn’t be here for dinner tonight. I only warned you three times yesterday.

Not surprisingly, nearly half of those interviewed said their biggest problem was someone who apologized unintentionally.

But I think most of the time we ask for forgiveness simply to show goodwill and avoid confrontation.

For example, when that young woman accidentally hit me with her umbrella while she was glued to her phone, I might have expressed my feelings more honestly if I had said, “Watch where you’re walking, you idiot!”

But this could well have led to a torrent of abuse, or in these violent times, perhaps something worse.

By muttering “I’m sorry,” she was instead saying, “Okay, we both know you’re the one to blame, but I’m a reasonable person, I know it wasn’t intentional, and I’m not going to make a big deal out of it.”

Call it shyness if you like. I prefer to think of it as politeness. But I have to admit that it is much easier to ask for forgiveness when we are clearly innocent than when we are actually guilty.

Indeed, nowhere is this truer than in the Westminster bubble, where politicians do not hesitate to slavishly apologise for the mistakes and shortcomings of others, whilst displaying the deepest reluctance to ask forgiveness for those for which they themselves are responsible.

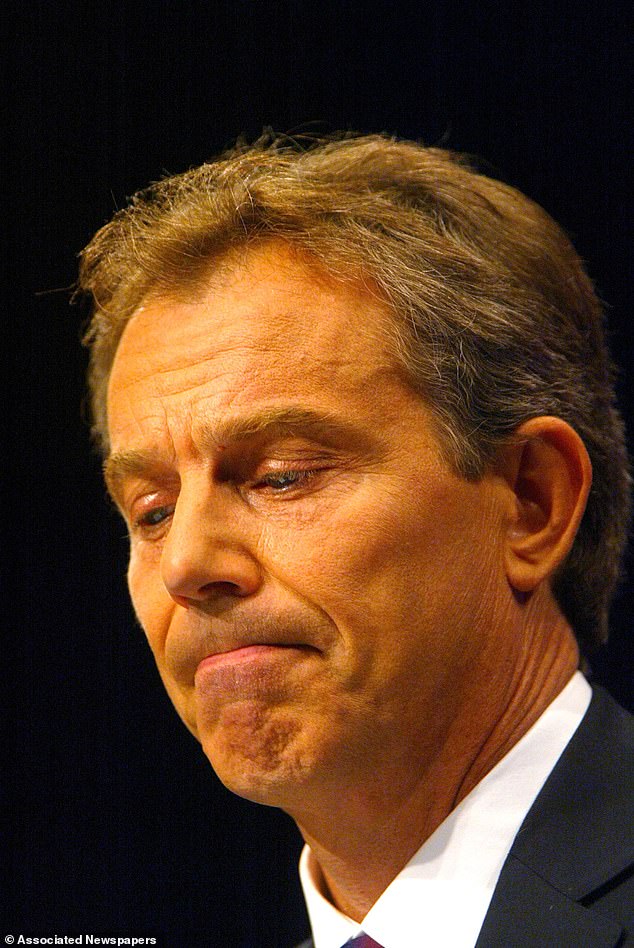

Consider Tony Blair, who was happy to apologise for Britain’s failure to alleviate the Irish potato famine, 150 years after the event.

He also apologized for Britain’s involvement in the shameful slave trade, some two centuries after the country led the world in abolishing it.

But while he expressed sincere contrition for the sins of the Stuarts, the Hanoverians and the Victorians, he showed no such willingness to apologize for his own catastrophic mistakes.

Take the Iraq war, for example. True, he eventually issued an apology of sorts, after the Chilcot inquiry found him guilty of a wide range of errors, from deliberately exaggerating the threat posed by the Iraqi regime to ignoring warnings about the potential consequences of military action.

But as soon as he said he accepted “full responsibility without exception or excuse” for the consequences of that war (which continue to this day), he offered a raft of excuses, rejected most of Chilcot’s criticisms and insisted that almost all of his own decisions were for the best.

He was sorry, of course, but only because he had been criticized.

This week, he was at it again, steadfastly refusing to apologise for opening our borders to mass immigration. When asked by the BBC’s Amol Rajan whether his policy had been a mistake, he replied with a resounding “no”.

He should try to convince the millions of people waiting for a hospital appointment or a home of their own that he bears no responsibility for the way public services have collapsed under the weight of the figures.

Keir Starmer is no better at admitting his own mistakes. This week, he was quick to offer his sincere apologies to all those who had suffered during and after the catastrophic Grenfell Tower fire – for which, of course, he was not personally to blame.

But try to get him to apologise for taking away winter fuel allowance from pensioners who need it, whilst giving £10,000 pay rises to train drivers who already earn £65,000 a year. Oh no, he’ll tell you. Those decisions may have been mine, but they were all the fault of the Tories!

But it’s not just Labour politicians who struggle to express convincing regret. How about this apology from Conservative Liz Truss, after her reckless mini-budget sent mortgage rates sky-high? “I’m not saying I did everything absolutely perfect in the way I communicated policy, but what I am saying is that I faced real resistance and actions from the Bank of England that undermined my policy and created the problems in the market.”

As for my fellow Mail columnist and former prime minister Boris Johnson, there can hardly be a living politician who has had to offer more apologies, whether for breaking his own lockdown rules, misleading the Queen about the legality of proroguing Parliament, offending the people of Liverpool or, on one famous occasion, upsetting the entire population of Papua New Guinea over his love of a punchline.

Writing in 2006, when he was opposition spokesman on higher education, he said: “For ten years we in the Conservative Party have become accustomed to orgies of cannibalism and Papua New Guinea-style chief murders, and so it is with happy amazement that we watch the madness engulf the Labour Party.”

Papua New Guinea’s High Commissioner in London was furious, telling BBC Radio 4 that his comments were highly damaging to his country and “an insult to the integrity and intelligence of all Papua New Guineans”.

He had barely finished speaking when Boris issued his immortal “apology”: “I did not mean to insult the people of Papua New Guinea, who I am sure lead a life of blameless bourgeois domesticity in common with the rest of us.”

He added: “I would be happy to add Papua New Guinea to my global apology itinerary.”

A sincere expression of genuine regret? Or an ironic attempt to provoke another laugh?

If I have hurt you, dear Boris, then what can I say? Except I’m sorry.