Travis Kelce is set to host another Kelce Jam music festival in Kansas City this summer following the success of last year’s inaugural event.

Kelce, who promotes and hosts the festival, held the star-studded party for the first time in 2023 after he and the Chiefs became Super Bowl champions.

Now, after helping them retain the Vince Lombardi Trophy last month, the Kansas City tight end is set to throw another party full of live music, superstar guests and some of the city’s most famous food on May 18.

So what can fans expect if they go to the Kelce Jam?

Dailymail.com is ready with a full review of last year’s festival and what could be in store this time around.

Travis Kelce is set to host another Kelce Jam music festival in Kansas City this summer

So what can fans expect in KC if they go to Kelce’s star-studded event on May 18th?

Live music

At last year’s Kelce Jam, which took place on NFL Draft weekend, Travis’ good friends Machine Gun Kelly and Rick Ross headlined a musical lineup that also featured Loud Luxury and Tech N9ne.

Kelly, who grew up with Kelce in Cleveland, was joined by her good friend at one point in the performance, and the pair belted out a rendition of ‘Fight For Your Right’ by the Beastie Boys.

The Chiefs star also got involved in Ross’ performance on the night and is likely to do the same again this year.

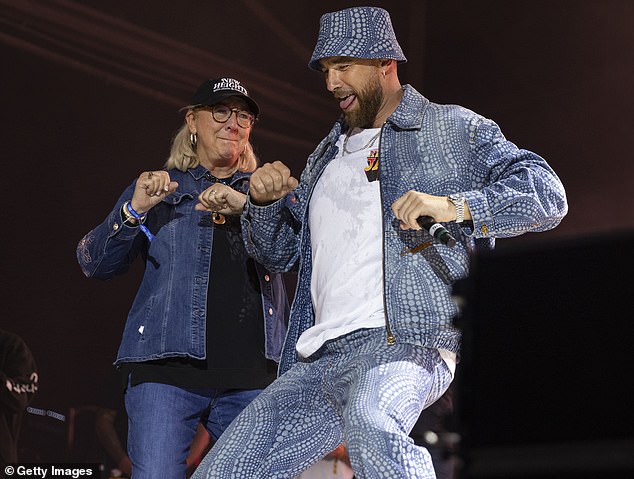

And of course, Kelce’s mom Donna also showed her face on stage as her son entertained the crowd.

However, it is currently unclear which artists he will book for the festival in 2023.

An obvious guest could have been girlfriend Taylor Swift, the pop megastar he has of course been dating for the past year.

Still, Swift won’t be able to join her NFL star beau at the event, as she has Eras Tour dates in Stockholm, Sweden, from May 17-19.

She does, however, have an endless supply of famous musical friends, which could come as a huge help to Kelce as he plans the festival.

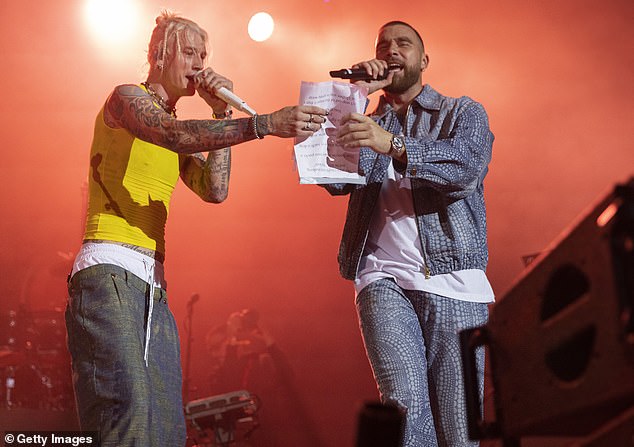

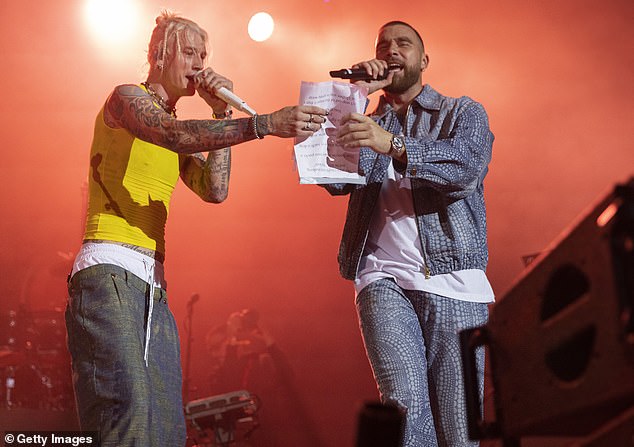

Last year, Travis’ good friend Machine Gun Kelly headlined a lineup of stellar musical guests

Kelce even joined Kelly on stage belting out ‘Fight For Your Right’ by the Beastie Boys

His mother Donna also couldn’t help but get involved in the festivities at last year’s festival

But there will be no Taylor Swift this year, as Kelce’s girlfriend is going on tour in Sweden

Regardless of who is in Kansas City, it promises to be another epic night after more than 20,000 fans packed the Azura Amphitheater in Bonner Springs – where it will be held again this year.

And given that Kelce’s fame has skyrocketed ever since he and Swift went public with their relationship, the demand is sure to be even higher in 2024.

Food and drinks

Not only will it feature a host of amazing musical guests, but Kelce Jam also promises to include some of the finest food Kansas City has to offer.

In 2023, fans were able to get caught up in some of the city’s legendary BBQ cuisine from famed restaurants Joe’s – which boasted a special ‘Kelce combo’ combining Kansas ribs and sausage with a Cleveland mustard-inspired BBQ sauce – and Jack Stack.

Hawaiian food was also on offer from Hawaiian Bros, while Longboards Wraps and Bowls also provided a mix of island flavors and KC food culture.

VIP ticket holders could even enjoy a complimentary BBQ from another popular Kansas hotspot, Q39, in a special VIP clubhouse and lounge.

Kelce Jam also boasted hot dogs, pretzels and nachos along with a selection of beer and liquor options for those in party mode (and over 21).

It remains to be seen what food options Kelce will serve up at his event this year, but if 2023 is anything to go by, festival-goers are unlikely to be disappointed.

Fans at the 2023 event could enjoy some of Kansas City’s famous BBQ cuisine

VIP ticket holders were offered free BBQ from a popular Kansas hotspot, Q39

Kelce also mingled with festival goers who partied the night away with beer or liquor

Interactive experiences, games and much more

Being one of the most flamboyant characters in the NFL, it wouldn’t be a Travis Kelce festival without fun and games.

And last year’s event certainly brought plenty of that, with two fans even taking part in a chicken wing eating contest up on stage during the musical show.

There will also be a number of interactive fan experiences on the day, which previously included an NFL kicking challenge for fans to try their luck at.

Kelce himself was also able to mingle with festival-goers last time, sharing a drink with fans and posing for pictures.

And for anyone looking to take home a souvenir, Kelce Jam will also boast merchandise available for purchase at the event.