A party animal loaded with great jewelry and fabulous furs.

Caught in a love triangle with a duchess and her husband, expelled from Britain, Spain and Italy, she was almost murdered on her wedding day and ended her days living off royal handouts.

It wasn’t all beer and bowling being Queen Ena of Spain.

Born in Balmoral, she was the granddaughter of Queen Victoria (Princess Beatrice’s daughter) and spent her happy childhood years at Kensington Palace.

She would later be remembered as the great-great-grandmother of Spain’s current king, Philip VI, but only after a turbulent life that encompassed hemophilia, the Spanish flu pandemic, the Spanish Civil War and exile.

The children of Princess Beatrice and Prince Henry of Battenberg. Princess Victoria Eugenia (Ena), the future queen of Spain is on the left

Princess Beatrice, Queen Victoria’s youngest daughter, is pictured with her four children. From left, they are: Ena, Leopold, Maurice (in sailor suit) and Alexander, 1st Marquis of Carisbrooke.

Queen Victoria surrounded by members of the royal family at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, including Princess Ena, third from the right.

Possessed of striking aquamarine eyes, she was “libertinary and very obscene in her conversation,” according to chronicler Chips Channon.

In other words, more than a little naughty.

But tragedy stalked his steps. He inherited the “royal disease”, hemophilia, from his grandmother Victoria, which he would pass on to her children once he married.

No one took that possibility into account when 20-year-old King Alfonso of Spain evaluated her when he came to London looking for a bride.

Ena (or Princess Victoria Eugenie, as she was born) caught his attention and soon the couple became engaged.

Ena would later complain: ‘the British hated me because I converted to Catholicism; The Spaniards hated me because I was not born Catholic.’

That turned out to be the least of his worries.

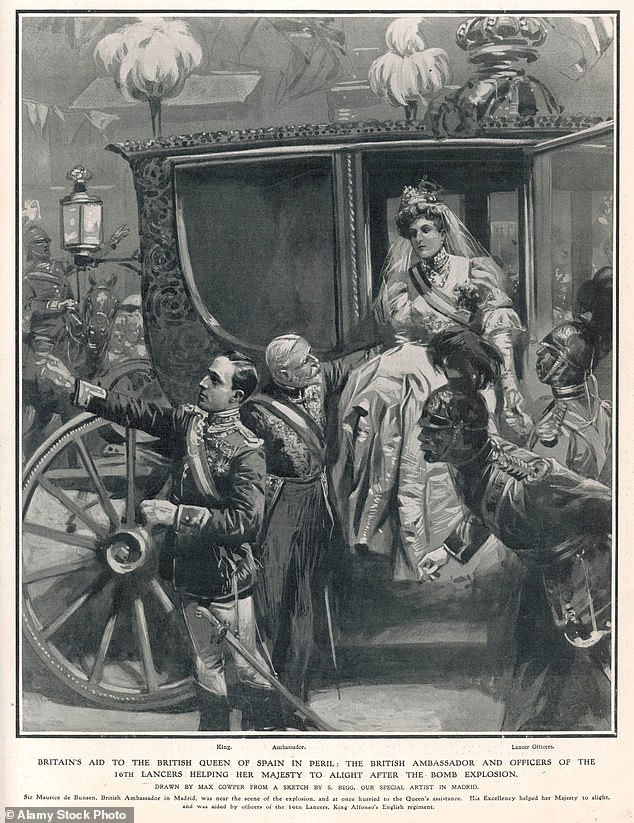

On her wedding day in 1906, an anarchist threw a bomb hidden inside a bouquet at a passing royal carriage.

Ena and her new husband were unharmed, but the blood of the fatally wounded mounted escort splattered on her wedding dress, a terrible omen for the future.

The revolution was already in the air in Spain and there was much more waiting around the corner.

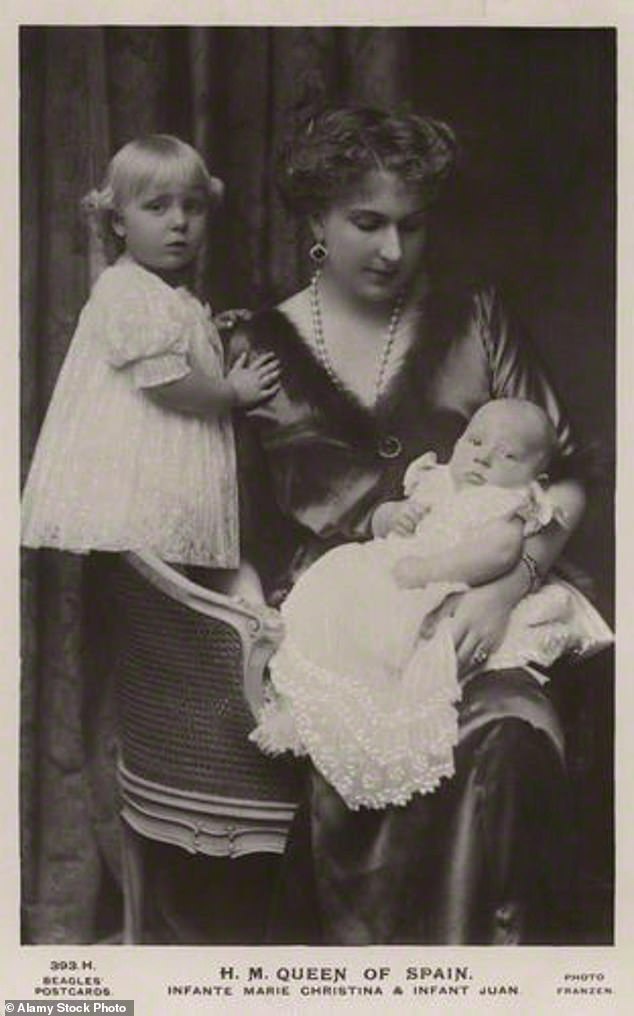

A year after the wedding, the couple’s first son, Alfonso, Prince of Asturias, was born, but almost immediately it was discovered that he suffered from hemophilia, which meant the inability to stop bleeding from any accidental wound.

The effect on the king was devastating and, in a valiant effort to rectify the situation, Ena allowed herself to become pregnant almost immediately: the following year she gave birth to a second son. Unfortunately, when she was four years old, this child could not speak or hear.

The King of Spain, Don Alfonso XIII (1886-1941) and his wife, Queen Victoria Eugenia, known as Princess Ena of Battenberg at the time of their wedding in 1906.

A period illustration showing the British ambassador and officers of the 16th Lancers helping Queen Ena descend after the bomb explosion.

Ena, Queen of Spain with her children Infanta María Cristina and Infante Juan in 1913

Five more births followed (seven children total in seven years), including a stillbirth, and all the love the couple once had evaporated long ago.

The Spanish, who had never liked their English queen, took her misery lightly. A popular verse at the time said:

One month of pleasure/Eight months of pain;

Three months of leisure/ And again;

Oh what a life/ For the Queen of Spain!

Alfonso had a series of lovers in revenge for bringing the scourge of hemophilia to the Spanish royal house, and after 15 years of marriage, the couple separated.

They had been expelled from the country before the Civil War that brought General Franco to power and had moved to Rome.

Although the King had slept with numerous women, it was Ena’s relationship with Duchess Rosario Lecera and her husband the Duke that finally caused the breakup.

The king angrily accused his wife of having an affair with the duke, to whom she was very close.

But according to Ena’s biographer Gerard Noël, the duchess, unbeknownst to the king, was also in love with Ena.

“Ena had no such inclinations,” he writes defensively, “although the duchess’s were well known; over the years, several governesses and maids had been dismissed from service under mysterious circumstances.”

But significantly when the king ordered his wife to choose between him and the duke, Ena responded in the plural: she would not give up the husband OR the wife.

Ena was told to leave Italy and returned to England to rent a house near Kensington Palace where her mother, Princess Beatrice, still lived.

Although war clouds were gathering in Europe, she felt safe there and embarked on a busy social life, being a popular guest at many parties. Her days of wandering were over.

Then, one day in late August 1939, Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden knocked on his door. He had come to tell him to leave the country.

He said he could not guarantee their safety in England should war break out. He was technically no longer a member of the British royal family, even though his first cousin was King George VI.

You should pack your bags and go.

Their unspoken reason: she could be a security risk. No one knew if Spain would enter World War II and, if it did, which side it would be on.

Ena urgently called the king at Buckingham Palace, but he did not return her call. Instead she wrote him a note saying: “I hope you are not away for long and that it is still possible to visit Balmoral.”

He didn’t mean it, and Ena knew it. Her royal cousins had abandoned her to her fate.

Ena, now queen of Spain, with her eldest daughter, Infanta Beatriz

He fled to Switzerland, where he remained untouched by the war.

From time to time, Queen Mary sent her money (strictly against wartime monetary restrictions) to keep her afloat.

The Queen of Spain swore bitterly never to return to Britain again.

Upon her death in 1969 she was buried in Lausanne.