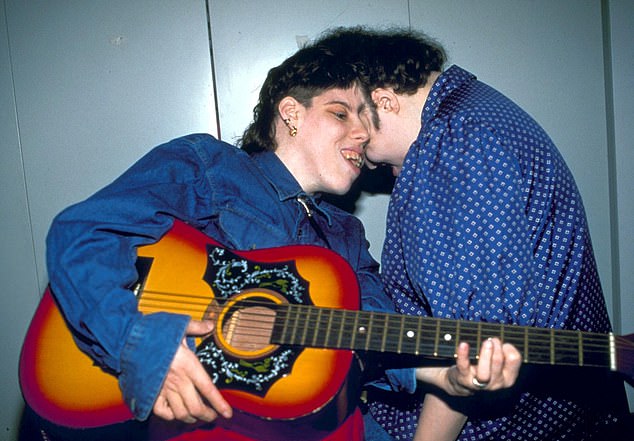

The world’s oldest conjoined twins, Lori and George Schappell, died at the age of 62.

Lori and her transgender twin George died Sunday in a Pennsylvania hospital of undisclosed causes, according to their online obituaries.

The brothers, who had partially fused skulls and shared 30 percent of their brains, defied doctors who said they would not live past 30.

The twins had previously made headlines after George, formerly Dori, came out as transgender.

The world’s oldest conjoined twins, Lori and George Schappell, died at the age of 62.

Lori and her transgender twin George (seen as babies) died Sunday in a Pennsylvania hospital due to undisclosed causes, according to their online obituaries.

Lori was healthy, but George, who had spina bifida, was confined to a wheelchair that his twin pushed.

He had enjoyed a successful career as a country singer, but Lori pursued her interests elsewhere as a trophy-winning bowler.

He also worked in a hospital laundry room for several years during the ’90s, organizing his schedule around George’s concerts, which took them around the world to countries like Germany and Japan, according to the Guinness World Records.

The brothers became the first conjoined same-sex twins to identify as different genders after George, whose original name was Dori, came out as a transgender man in 2007.

It was at this point that she changed her name from Reba, a nickname she adopted to honor her idol Reba McEntire because she didn’t like her rhyming names, to George.

The twins lived independently in a two-bedroom apartment in Pennsylvania, where they took turns pursuing their separate hobbies.

They alternated which room they slept in and also showered separately using the shower curtain as a barrier while one was outside the bathroom.

The couple appeared on numerous shows, including Jerry Springer, The Maury Povich Show and The Howard Stern Radio Show.

The brothers, who had partially fused skulls and shared 30 percent of their brains, defied doctors who said they would not live longer than 30 years.

George had enjoyed a successful career as a country singer, but Lori pursued her interests elsewhere as a trophy-winning bowler.

In the past, when asked if the death of one would necessarily mean the death of the other, Lori said at the time, “No, it wouldn’t.” That’s another misconception.”

George, then Reba, explained in the 1997 documentary: “If caught in time, we could both be rushed to the hospital and then, in an emergency, quickly separated to save the other.”

Delving deeper into whether they had ever wHe wanted to separate us, he said no: ‘Would we be separated? Absolutely not. My theory is: why fix what isn’t broken?’

“Just because we can’t get up and walk away from each other doesn’t mean we can’t be alone with other people or ourselves,” Lori added. “People who are close can have very private lives.”

She also shared her dreams of one day having a family of her own, explaining, “Eventually I would love to have a family: a husband and children of my own.”

Interviewer Antony Thomas then asked George if he would share intimacy with a future husband, to which he replied: “He would be like a brother-in-law to me, that’s all.” They can do whatever they want and I would act like I’m not even there. I would block it.’

The twins defied all predictions from medical professionals that they would not live past 30 years.

They became the oldest conjoined twins in history in 2015, surpassing Masha and Dasha Krivoshlyapova, who died at age 53.

Lori and George are survived by their father, six siblings, and several nieces and nephews.

It comes after Connecticut-based conjoined twins Carmen and Lupita Andrade, 23, detailed what happens if one of them dies.

The sisters, who moved to the United States from Mexico when they were two years old, share all organs and limbs below the waist.

When they were born, doctors told their parents they would probably only live a few days, but they have defied the odds and are now thriving.

Carmen recently opened up about some of the confrontational and brave messages they receive regularly, including what will happen if one of them dies.

“We share a bloodstream, so sepsis will eventually set in and obviously within hours or days the other one will die,” he explained. ‘But we’re not dead, so why always ask ourselves that?’