The first privately owned spacecraft is currently on the Moon, preparing to search for signs of water in the lunar landscape.

Odysseus, a $118 million unmanned lander built by Intuitive Machines, made a soft landing near the Moon’s south pole at 6:24 p.m. ET on Thursday.

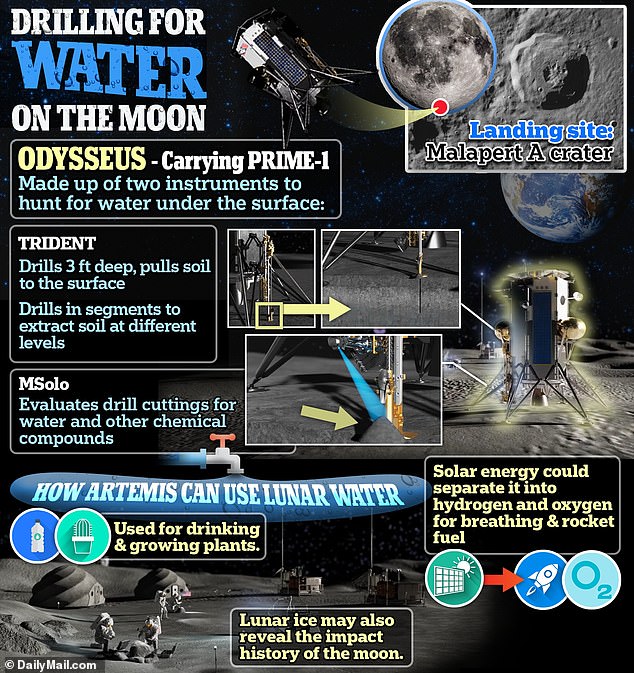

NASA’s Polar Resources Ice Mining Experiment 1 is moored to the outside of the spacecraft, which will soon burrow into the surface, collect regolith, and analyze lunar dust with a suite of powerful instruments.

The mission will assist astronauts who will soon investigate the Moon, allowing them to use water for hydration, fuel and even breathing, ultimately establishing a human presence.

The first private spacecraft is currently on the Moon, preparing to search for signs of water in the lunar landscape.

“Thanks to data from spacecraft orbiting the Moon, scientists believe that the polar regions are rich in water beneath the lunar surface,” NASA shared in a statement.

‘But we have (never) explored these regions or directly detected water.

“PRIME-1 will help identify and assess water abundance and quality in an area expected to contain ice.”

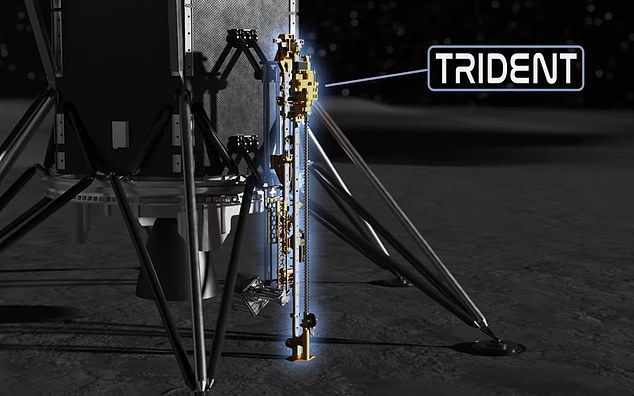

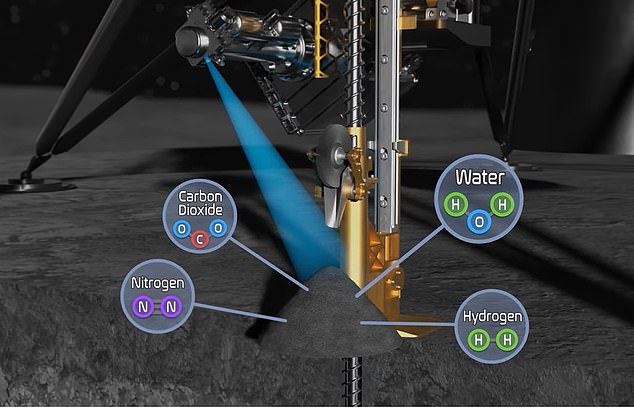

PRIME-1 consists of two instruments: the regolith and ice drill for exploring new terrain (TRIDENT) and the mass spectrometer observing lunar operations (MSolo).

TRIDENT will drill up to a meter deep, extracting lunar regolith, or soil, to the surface.

The instrument was designed to drill in multiple segments, stopping and retracting to deposit cuttings on the surface after each increase in depth.

TRIDENT will drill up to a meter deep, extracting lunar regolith, or soil, to the surface. The instrument was designed to drill in multiple segments, stopping and retracting to deposit cuttings on the surface after each increase in depth.

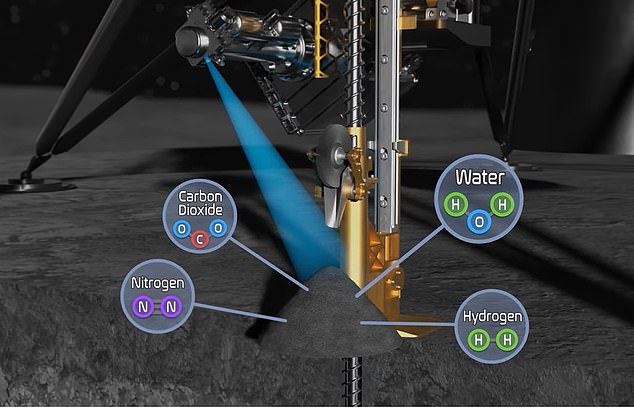

Once the samples are on the surface, MSolo will evaluate the drill cuttings for water and other chemicals. The tool is a mass spectrometer, which can measure the mass-charge ratio of ions.

Once the samples are on the surface, MSolo will evaluate the drill cuttings for water and other chemicals.

The tool is a mass spectrometer, which can measure the mass-charge ratio of ions.

The instrument is used in drug testing and discovery, food contamination detection, pesticide residue analysis, isotope ratio determination, protein identification and carbon dating.

“Data from PRIME-1 will help scientists understand in situ resources on the Moon, including mapping the location of resources,” NASA shared.

“PRIME-1 contributes to NASA’s search for water at the Moon’s poles, supporting the agency’s plans to establish a sustainable human presence on the Moon by the end of the decade.”

“Data from PRIME-1 will help scientists understand in situ resources on the Moon, including mapping the location of resources,” NASA shared.

MOnly will look for specific compounds that indicate water is below the surface

The space agency hopes to put American boots on the Moon again in 2026 (the last time was in 1972).

Intuitive Machines revealed on Friday that Odysseus is “alive in the well.”

‘Flight controllers are communicating and ordering the vehicle to download scientific data. The lander has good telemetry and solar charging,” the company shared in X.

During his 73-minute descent, Odysseus, or Oddie, slowed from 6,500 kilometers per hour (4,000 mph) to make a soft landing in a cratered area.

However, the mission almost ended in failure when the ship was forced to switch to an experimental navigation system mid-landing.

‘I know this was a nail-biter, but we’re on the surface and we’re transmitting. Welcome to the moon,” said Intuitive Machines CEO Steve Altemus.

The ship was launched last week ora SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida.

The uncrewed spacecraft had been orbiting the moon about 57 miles above the surface since reaching orbit on Wednesday.

Odie remained “in excellent health” as it continued to orbit the moon, approximately 239,000 miles from Earth, transmitting flight data and lunar images to Intuitive Machines’ mission control center in Houston, the company said Wednesday.

But as he moved into the final stages of the operation, Odie’s handlers discovered that the laser rangefinders were not working.

This vital system is what allows the spacecraft to determine how far it is above the lunar surface and can make the difference between a soft landing and an accident.

Using a last-minute software patch, engineers were able to convert NASA’s experimental Navigation Doppler Lidar, which was carried on the payload, to take on the job.

At 6:11 pm EST, Odysseus ignited its engine during the crucial 11 minutes of burning, decelerating from 4,000 mph (6,500 kph) to just 2.2 mph (3.5 kph), 33 feet above the surface.

Having broken his fall, Odie landed safely on the rim of the giant crater Malapert A, about 190 miles (300 kilometers) north of the moon’s south pole.

After 15 tense minutes, the crew back on Earth finally received Odie’s signal, confirming that the landing had been a success.

Shortly after receiving the signal, mission director Tim Crain said, “What we can confirm without a doubt is that our equipment is on the surface of the moon and we are transmitting.”

“Houston, Odysseus has found his new home.”

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson added, in a statement about X, that Odysseus had “achieved the landing of a lifetime.”

The landing marks the first time since 1972 with the last Apollo mission that a US spacecraft has made a successful landing on the moon.

Although the lander was built by Intuitive Machines, NASA partly funded the operation by purchasing cargo space aboard the Odysseus.

This also marks the first moon landing using a rocket from Elon Musk’s SpaceX, which Intuitive Machines paid $130m (£103m) to launch.

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said in a video congratulating everyone involved: “We have conquered the moon.

‘Today, for the first time in more than half a century, the United States has returned to the Moon.

“Today is a day that shows the power and promise of NASA’s commercial partnerships,” he added.

“Congratulations to everyone involved in this big, daring search.”

The magnitude of this challenge is highlighted by the recent failures of other landing attempts.

Odie’s mission comes a month after another private company unsuccessfully attempted to land on the Moon.

Astrobotic Technology attempted to return the United States to the lunar surface with its Peregrine, but the lander suffered a propulsion system leak on its way shortly after being launched into orbit.

More recently, the Japanese SLIM lander successfully landed on the Moon, but ended up stuck upside down due to engine failure during landing.

The mission was made even more difficult by Intuitive Machine’s choice of landing site.

Malapert A Crater is a rocky area filled with craters that could destabilize or bring down a lander.

However, it is also believed that this region near the Moon’s south pole could be rich in frozen water that could be essential for a future lunar base.