Has your life plunged into chaos? Or maybe you’ve started to feel homesick or even want to completely change your appearance after going through a bit of an identity crisis?

No, it’s not random: Mercury is once again retrograde and Generation Z is flocking to social media to warn others and prepare for the potentially turbulent time ahead.

About four times a year, over a three-week period, Mercury goes into retrograde, meaning it appears to stop and recede in the sky, and during that time, many people believe that the planet’s movements can change things in their lives. . go wrong.

From a layoff at work to problems in your love life, many people are convinced that this cosmic event can cause a series of misfortunes; some even claim to make decisions they normally wouldn’t make right now, so they avoid big choices altogether.

Here, FEMAIL looks at what the world is saying as Mercury goes retrograde for the first time in 2024.

About four times a year, over a three-week period, Mercury goes into retrograde, meaning it appears to stop and recede in the sky.

The planet began its apparent retrograde on April 1 and will continue until April 24, this being retrograde in the sign of Aries.

What’s more, one astrologer has warned that this Mercury retrograde may cause even more chaos than usual, as it takes place during eclipse season.

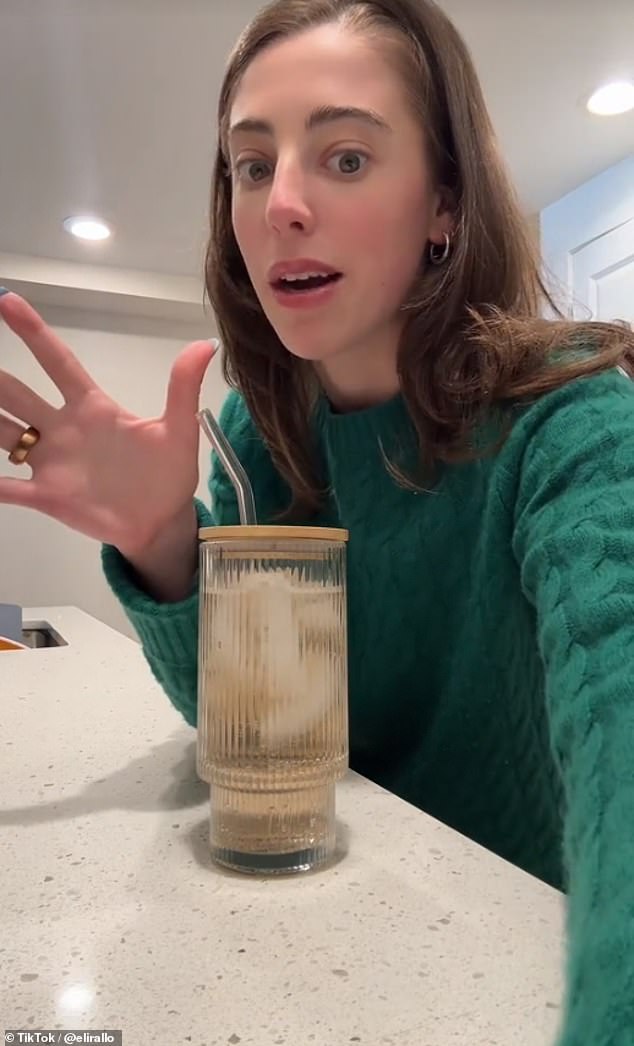

Eli Rallo, a US influencer, took to TikTok to warn her 822,000 followers to be careful what they do during this time and not to text her ex.

In a video seen by more than 1.6 million people, published under his name @eliralloHe talked about his advice for the season.

She said, ‘I’m going to tell you what to do and what not to do, okay? This shit is real. Women in STEM, planets, science, listen to me.

‘You may feel nostalgic, sad, you may feel like you want to get closer to an ex or a friend who was toxic.

‘Don’t do it, wait until April 25. Because? Because naturally, during a retrograde, you’re going to feel more nostalgic, more attached to the past, more reflective about the past, and that might make you feel like you want to reach out to someone you don’t have to.

‘You can wait 24 days, I know you can, they will still be there. If possible, you may want to postpone making important decisions in life, just because you will feel like a lot of things are going wrong.

Eli Rallo, a US influencer, took to TikTok to warn her 822,000 followers to be careful what they do during this time.

The American added: “You may have technological difficulties or glitches, you may simply feel frustrated because things are not going your way, and you may have difficulty with everyday tasks.”

“It’s simply a better idea not to make big life changes or decisions, if possible, and to sign big contracts, if possible.”

‘Having said all that, it is a very good time to reflect and think about how things have been going in your life and the things you want to change.

‘Decide how you feel about your life, what works and what doesn’t. When things go wrong and you get frustrated, ask yourself questions about it and interrogate it. “It’s a good time to get nostalgic and really feel what you’re feeling.”

She ended the clip promising, “Once we’re on the other side of this, we’ll feel lovely, stunning, beautiful, beautiful.” If you feel bad today, Mercury is in retrograde, let’s get through it together.

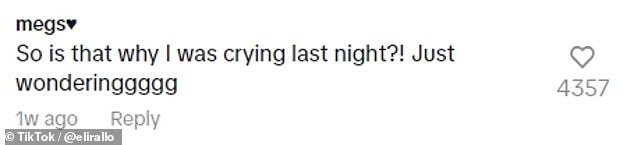

Shocked commenters joked: ‘So that’s why I was crying last night?!’ I was just wondering’ and ‘Oh, so crying 4 times yesterday makes sense now.’

A third warned: ‘I got close. NO. No. Stop. No no. Stay strong, friends.

Meanwhile, a fourth admitted: “I was literally talking about how nostalgic I felt all day,” and a fifth commented: “Yes, I feel 7 different ways today.”

Others asked: ‘Uhhh, I need a new job, should I wait until April 24?’ and ‘Lol he’s literally getting married on Friday…’ Oops.’

In a video viewed by more than 1.6 million people, posted under his name @elirallo, he talked about his advice for the season.

Shocked commenters joked: ‘So that’s why I was crying last night?!’ I was just wondering’ and ‘Oh, so crying 4 times yesterday makes sense now’

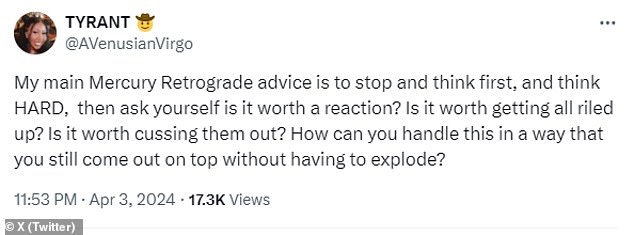

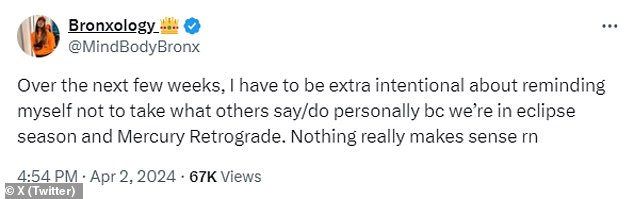

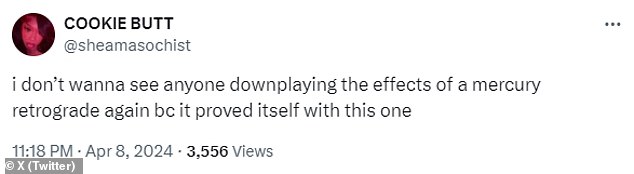

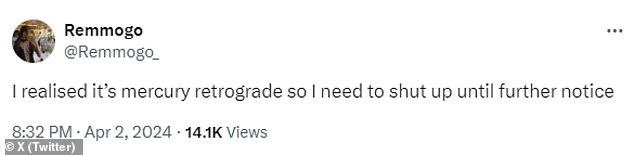

Users of X (formerly Twitter) have also been issuing warnings about the planet’s visual change in direction and how it may affect it in more ways than one.

Someone insisted: “I don’t want anyone to downplay the effects of a Mercury retrograde again because it has already proven effective with this one.”

A second agreed: ‘Over the next few weeks, I have to be very intentional about reminding myself not to take what others say and do personally because we are in eclipse and Mercury retrograde season. Nothing really makes sense right now.’

A third joked: “I see they went more retrograde this Mercury retrograde,” and a fourth asked: “Mercury retrograde made everyone show they’re screwed, why is everyone arguing?”

One user who doesn’t seem to be affected wrote: ‘This Mercury retrograde really helped me see that I don’t miss anyone from my past. As if I didn’t lack a soul, growth!’

Meanwhile, another user reasoned: “Arguments during Mercury retrograde are fun, because usually both people are right in some way.”

Someone else gave some guidance and wrote: ‘My main advice about Mercury retrograde is to stop and think first, think HARD, and then ask yourself if reacting is worth it.

‘Is it worth getting angry? Is it worth insulting them? How can you handle this in a way that you still come out victorious without having to explode?

Users of X (formerly Twitter) have also been issuing warnings about the planet’s visual change in direction and how it may affect you in more ways than one.

Another chimed in: “Mercury retrograde starts today, we all need to shut up and stay silent.”

‘Everyone, it’s only the third day of April and Mercury retrograde is already coming towards my head. “I’m trying to control my attitude and my anger,” admitted one social media user.

The warnings come just after yesterday’s solar eclipse, the biggest astronomical event of the decade.

This rare event occurred when the Moon was moving directly between the Sun and Earth, resulting in incredible photo opportunities.

However, Americans reported strange physical and mental alignments before and during Monday’s solar eclipse.

Symptoms, called “eclipse disease,” include headaches, fatigue, changes in menstrual cycles and insomnia.

While NASA has said there is no evidence linking human health and the solar eclipse, studies have found that the celestial event can affect animals, specifically dogs who may appear anxious.

A total solar eclipse occurs when the moon and sun line up perfectly and the moon is close enough to us to cover the entire sun, from our perspective.

The last one to appear in the US was in 2017 and the next one is scheduled for August 23, 2044.