Discarded wartime service medals found on a street led to the discovery of the unmarked grave of a First World War soldier, lost and forgotten for almost a century.

The remarkable reconstruction of William McEwan’s tragic story has also sparked the fight to give him and hundreds of other forgotten Australian war heroes the official posthumous recognition their sacrifice deserves.

‘“Our William was an ordinary guy from an ordinary family who went and ‘did his bit’ like so many Australians, but sadly returned physically and mentally broken,” Melbourne military history enthusiast Peter Zabrdac told the Daily Mail Australia.

‘It is disgusting that his grave was never properly marked and that he has been forgotten for 99 years. I am determined to get him the military headstone he is entitled to.

Zabrdac’s father found William’s discarded medals on a Fitzroy street in inner-city Melbourne in the early 1970s.

Although they fascinated Mr. Zabrdac, who was in elementary school at the time, he forgot about them until earlier this year, when he found the military honors among his father’s belongings.

Zabrdac, now 59 and a semi-retired company director, did some research that led him to obtain William’s entire “beautifully handwritten” 79-page military file from the National Archives in Canberra.

“The more I read his file, the more human he becomes,” Zabrdac said.

The long-lost, unmarked grave of William McEwan, a seriously injured First World War digger fighting for Australia

William McEwan was so seriously wounded in the 1916 World War I battle for the French town of Pozieres that the army wrote to his mother saying he was unlikely to survive.

William was only 5’3 (163 cm) tall, which originally prevented him from enlisting at Gallipoli.

After that disastrous campaign and other fighting, the Australian Army was forced to reduce altitude minimums to replenish its strength, which meant William was able to enlist and was sent to fight in France.

During the hellish four-month battle in 1916 for the French village of Pozieres, where the Germans unleashed their entire arsenal, including phosphorus shells and poison gas, William joined the 23,000 Australian casualties, with 6,800 killed or mortally wounded.

William was shot in both lungs and arms, in addition to receiving shrapnel wounds in the back.

“He was not expected to live and the army notified his poor mother accordingly,” Mr Zabrdac said.

“How he lived, only God knows.”

William was evacuated to England, where he spent 18 months recovering before being discharged in 1917 as unfit for further service.

Upon returning to live in Melbourne, William married but dr.He automatically and publicly took his own life in 1923.

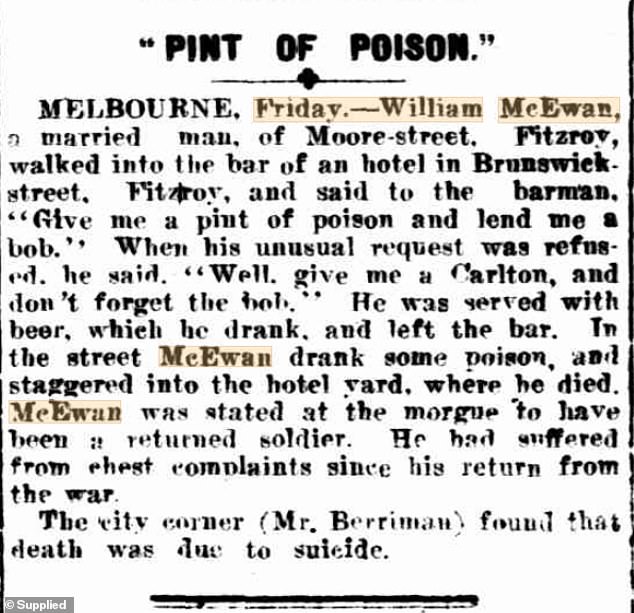

A death notice from the now-defunct Melbourne newspaper The Argus said William walked into a pub in Brunswick, near Fitzroy, where he lived, and told the barman to pour him “a pint of poison” and lend him a “bob.” (12 pence in pre-decimal currency).

One of William’s medals found apparently discarded on a Fitzroy street in the early 1970s.

When this “unusual request” was refused, William ordered a beer, which he drank but then went out into the street and “drank some poison and staggered into the hotel courtyard, where he died.”

“He had suffered chest pains since returning from the war,” the Argus reported.

Zabrdac said that with the help of Faith Jones of the Virtual War Memorial group and Lois Comeadow of Brighton Cematorians, she was able to locate not only a living relative of William but also the war hero’s grave.

However, Zabrdac was shocked and dismayed to see William lying anonymously in an unmarked location in Brighton Cemetery, located in the southeastern Melbourne suburb of Caulfield South.

‘“Our William was an ordinary guy from an ordinary family who went and ‘did his bit’ like so many Australians, but sadly returned physically and mentally broken,” Mr Zabrdac said.

“It is disgusting that his grave has never been properly marked and that he has been forgotten for 99 years and I am determined to get him the military headstone to which he is entitled.

William’s extraordinary 1923 death notice contained in his military file from the now-defunct Melbourne newspaper The Argus.

Mr. Zabrdac has been informed that the Department of Veterans Affairs will only designate William as eligible for a war grave and provide him with a ceremonially engraved headstone, valued at about $7,000, if it can be proven that he died from wounds in the battlefield.

“So far all we have is the statement from his landlady that the police took, where she stated that she ‘suffered terrible breathing problems,'” Mr. Zabrdac said as he prepared a presentation.

Zabrdac noted that families of American veterans always have a dedicated place to honor their deceased loved ones.

“The Americans have Arlington Military Cemetery (in Washington) for their returning servicemen, but we don’t do anything in Australia and it’s shameful,” he said.

“There are many other diggers across Australia in similar situations, forgotten and lying in unmarked graves.”

Peter Zabrdac (pictured left) attends a flag ceremony at William’s grave with Victorian RSL State Committee member Ange Kenos.

Zabrdac attended a flag ceremony held at William’s grave last Friday, which also included members of the ADF and representatives of the Victorian RSL.

He said the heartfelt ceremony was just the beginning of the effort to honor William, and everyone in attendance vowed not to rest until they secured a headstone or memorial plaque for this previously unrecognized soldier.

Zabrdac also intends to present William’s medals to the only surviving relative he managed to locate, Wendy Newman, who lives in Queensland.

Between 1997 and 2021, there were 1,677 confirmed suicides among members and former members of the ADF, equivalent to 20 times the number of deaths in armed conflicts during the period.

The Department of Veterans Affairs has been contacted for comment.