to do the To get a perfect scoop of ice cream, you first need a dairy base: its proteins, fats, and natural sugars provide a rich, distinctive mouthfeel. Heavy cream is added, further softening the texture. The introduction of sugar isn’t just for sweetness: like sprinkling salt on snow, it lowers the freezing point, minimizing icing. Now you can add flavors to the mix, from the most essential (chocolate chips or vanilla beans) to the most daring (spices, salt or alcohol).

This recipe takes you a little less than halfway to the ideal portion. Next is the 0.5 percent emulsifiers and stabilizers that are added to the liquid, which helps the water content and fats stick together. The mixture is homogenized, then cooled and allowed to sit for 24 hours at 5 degrees Celsius (40 Fahrenheit), for an even richer, smoother flavor before freezing.

Then comes the secret ingredient. “We sell air,” says Elsebeth Baungaard Andersen, product manager at Swedish multinational food packaging and processing company Tetra Pak. “Half the volume of your favorite tub of ice cream is air. But it’s those air bubbles and whipped texture that provide a special mouthfeel as it melts in your mouth, releasing its delicious flavor.”

At Tetra Pak’s Product Development Center in Aarhus, Denmark, a laboratory for the largest and smallest ice cream brands to test and test their latest experiments, air is a precious and invisible commodity. During the freezing stage, in which the mixture is cooled to -5 degrees Celsius (23 Fahrenheit) inside a rotating cylinder, the Dasher’s scraper blades not only scoop out frozen batches of the good product, but also agitate the air. Stabilized by fat and protein globules, the air bubbles create that soft, familiar, luxurious feeling. “We have to be very precise with our dosing,” says Baungaard. “Ice cream is a science: too much air and it’s foamy, too little air and it’s hard to scoop and eat.”

The exact dosage depends on the recipe: the lower the excess (that is, the percentage by which air increases the volume of the mixture), the more premium the product. An artisanal ice cream has a denser texture; its excess may be only 20 percent. Inexpensive ice cream from supermarkets can have an extra cost of even more than 100 percent.

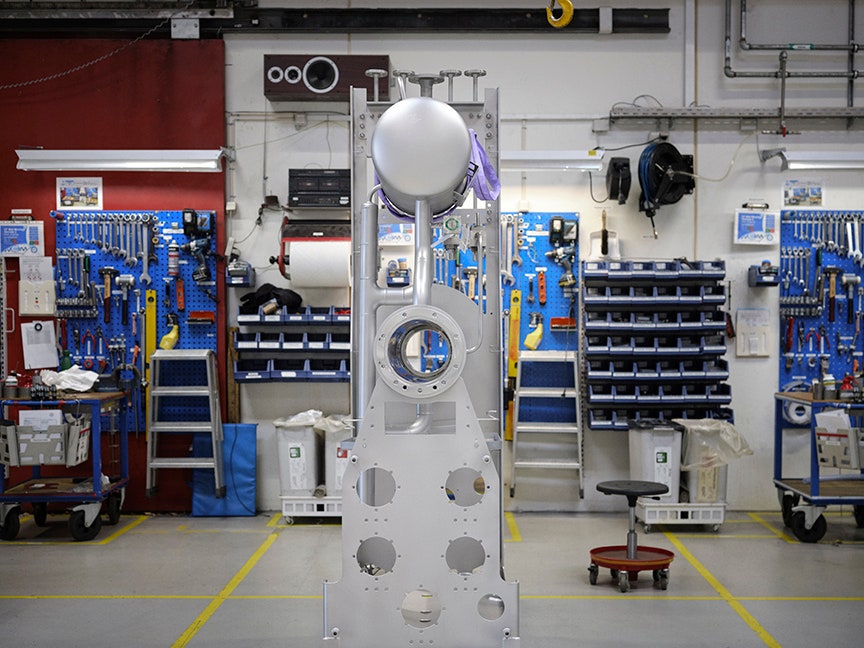

This is just part of the complex chemistry involved in making the world’s favorite dessert. Tetra Pak may be most famous for its packaging, but it takes a hefty bite out of the estimated price. Ice cream industry valued at $113 billion: Each of their continuous freezers pumps 4,000 liters every hour, typically for small producers looking to scale. In addition to the tubs, its production lines produce 2 million ice cream sticks every day. Major customers also use their Aarhus facilities to test new concepts. (“We’re in the Silicon Valley of ice cream,” Andersen says.)

In fact, Tetra Pak ice cream engineers have innovated the industry: in the late 1980s, their technology meant that ice cream could be extruded into a stick at a colder temperature, which meant more air bubbles, creating a more premium flavor. The product became the Magnum Classic. Today, collaborative robots (or cobots) ensure that portions are not generously overfilled at the factory and that each spoonful has the same amount of sauce. Meanwhile, their human colleagues are testing new prototypes using 3D printers.