Australia is addicted to high immigration, so it may have more working-age people to tax as couples have fewer children and the population ages, a government report says.

The Treasury has warned that the alternative to high immigration would be even higher income taxes, as the over-70s will make up a larger proportion of the population in coming decades.

The Institute of Public Affairs, a libertarian think tank, estimated that a record 31 per cent of Australia’s population was now foreign-born – more than double the US level of 15 per cent and the UK’s 14 per cent. .

It is also significantly higher than Canada’s 21 percent and New Zealand’s 29 percent.

A record 518,000 migrants, on net terms, moved to Australia in the 2022-23 financial year. This figure dropped to 447,790 at the end of last year.

Australia is addicted to high immigration, so it may have more working-age people to tax as couples have fewer children and the population ages (pictured, a Sydney train)

But before taking into account long-term departures, almost 1.1 million foreigners moved to Australia permanently and long-term in 2023, data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics revealed.

Both Deloitte Access Economics and Treasury expect Australia’s overseas intake, which covers skilled migrants and international students, to fall to 375,000 in 2023-24.

This would still be almost double the pre-pandemic level of 194,400 in 2019-20, before Australia went into lockdown from March 2020 to December 2021.

Immigration increases labor supply

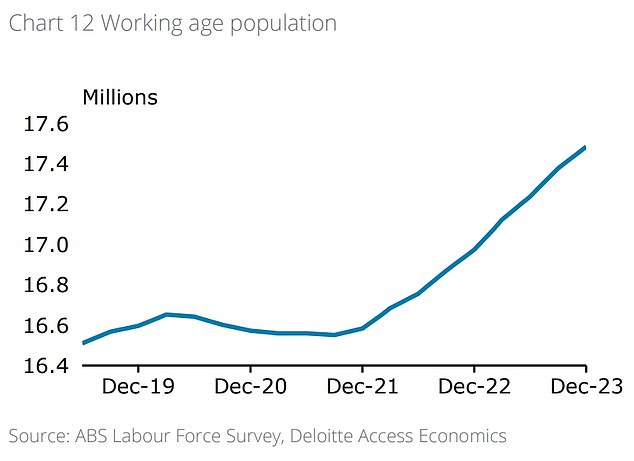

Deloitte’s ‘Right Sizing The Workforce’ report estimated that the recent surge in immigration meant the country was home to 693,600 more working-age people than before the pandemic.

In December there were 17.5 million people between 15 and 64 years old.

“That strength is largely due to the rebound in international migration, which gives Australia access to young and (in many cases) skilled workers,” the Deloitte report says.

“Australia’s population continues to strengthen thanks to record overseas migration.”

Australia’s fertility rate fell to just 1.7 in 2021, putting it well below the replacement level of 2, as people in first world countries have fewer children.

Baby boomers are retiring

Baby boomers also began to retire in large numbers in 2006, when the oldest turned 60 and could access their retirement.

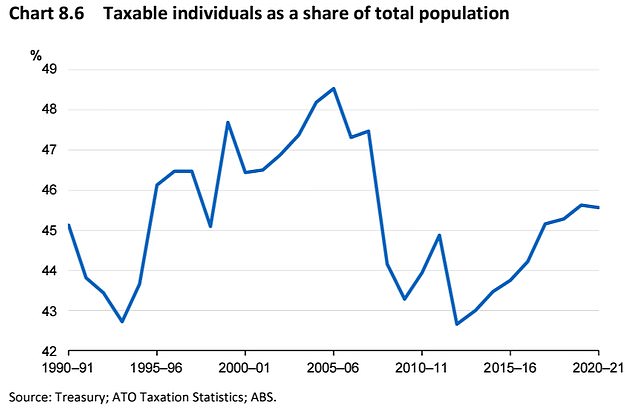

The working-age component of the Australian population peaked in 2005-2006, when 48.5 per cent of the population paid income tax and a large generation of Australians were still working.

That figure fell below 43 per cent in 2012-13, but rose again closer to 46 per cent in 2019-20, when net overseas migration again surpassed 200,000.

Higher income taxes

The Treasury’s Intergenerational Report, published in August, warned that the alternative to more immigration would be an increase in personal income taxes.

“As the population ages, the personal income tax base is expected to continue to narrow in line with the projected decline in labor force participation,” he said.

‘In the absence of policy changes, projections show increasing reliance on personal income tax.

“Taxpayers have declined as a percentage of the total population since peaking in 2005-2006, despite a similar employment-to-population ratio.”

The Treasury still expects personal income tax revenue to grow from 12 per cent of gross domestic product in 2022-23 to just above 14 per cent by 2062-63.

Only 12 per cent of Australians aged 70 and over pay income tax, and this group currently represents 12.2 per cent of the total population.

The number of elderly people was expected to increase to 18.1 percent in 2062-2063.

The Treasury has warned that the alternative to high immigration would be even higher income taxes, as the over-70s will make up a larger proportion of the population in coming decades (archive image pictured).

The working-age component of Australia’s population peaked in 2005-06, when 48.5 per cent of the population paid income tax.

Disadvantages of high immigration

Deloitte admitted that a reduction in temporary migration, based on large numbers of international students, would reduce demand for rental accommodation during a cost of living crisis.

“If the reduction in temporary migration were to materialize, it would likely help alleviate some of the supply-side pressures that have contributed to problems such as deteriorating rent and housing affordability,” he said.

Daniel Wild, deputy chief executive of the Institute of Public Affairs think tank, said high immigration was behind Australia’s housing crisis.

‘Migration has played and will continue to play a fundamental role in our social fabric and our national economy, but the lack of proper planning has directly led to housing shortages, increased household costs of living and has put pressure on our education, health and welfare systems. ‘ he said.

Deloitte’s ‘Right Sizing The Workforce’ report estimated that the recent surge in immigration meant the country was home to 693,600 more working-age people than before the pandemic (pictured, a Sydney bartender).

In December there were 17.5 million people between 15 and 64 years old.

Sydney’s median house price rose 12.8 per cent in the year to January to an even more unaffordable $1.395 billion, CoreLogic data showed, despite a series of aggressive price increases. Reserve Bank interest rates.

This came as Melbourne house rents soared 17 per cent year-on-year in February to $736 a week, separate figures from SQM Research showed.

Wild said high immigration was a lazy policy solution to address skills shortages.

“It is clear that the federal government’s immigration program is unplanned, out of control and out of step with community expectations,” he said.

‘On top of this, it has failed to address Australia’s worker shortage crisis, the very thing the federal government is using to justify such rapid increases in hiring.

“It is clear that this lazy approach to solving the worker shortage is not working and there should be a greater focus on getting Australian retirees, veterans and students into work.”