A cratered, rust-red, rock-filled wasteland that is arid, extremely cold, and devoid of plant life.

That’s an accurate practical description of Mars. But also this remote Canadian island, 1,000 miles south of the Earth’s North Pole.

Devon Island is the largest uninhabited island in the world and is part of the Canadian High Arctic archipelago, Nunavut. To the Inuit of Nunavut it is known as Taallujutit Qikiktagna – Jaw Bone Island.

For a small clique of scientists, it is Mars on Earth.

For two months in the middle of summer, when the ground is free of snow, researchers and their partners head to the Haughton-Mars Project base camp on the island to conduct research on how human explorers could live and work on other planets. Despite it being summer, temperatures rarely exceed eight degrees C and the average annual temperature is -16 C below zero.

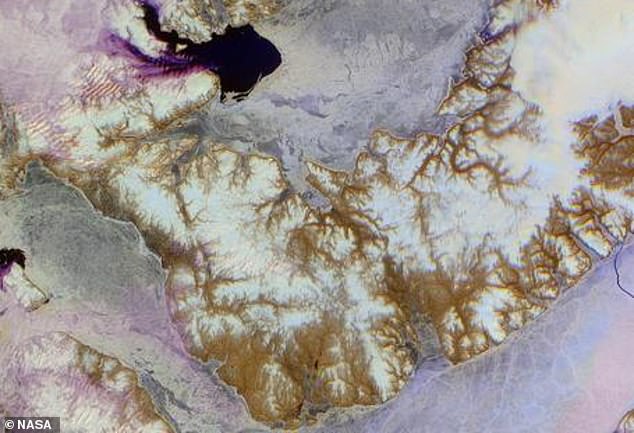

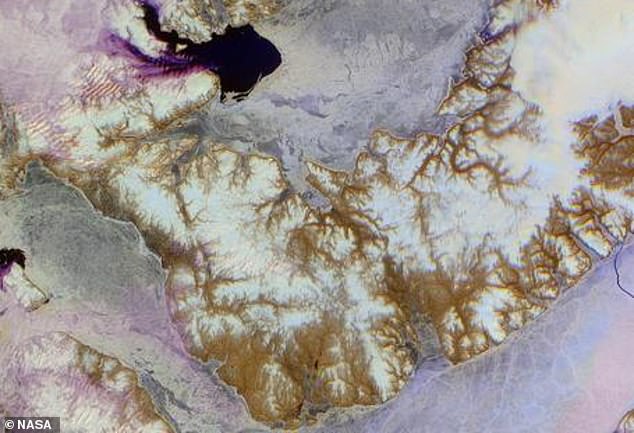

Devon Island (above) is the largest uninhabited island in the world and is part of the Canadian High Arctic archipelago.

Scientists use Devon Island, nicknamed Mars on Earth, to investigate how humans could colonize other planets. The epicenter of their work is one of the highest latitude “impact structures” on Earth: Haughton Crater. Above is a NASA rover exploring the otherworldly terrain of the crater.

An image acquired by the Nasa Terra satellite on June 28, 2001, showing Devon Island from above.

A rover and the Haughton Mars Research Project base camp in Haughton Crater

An aerial shot of the Haughton impact crater, which measures 14 miles in diameter.

The epicenter of their work is one of the highest latitude “impact structures” on Earth: Haughton Crater. It was formed about 23 million years ago, when an asteroid or comet collided with the planet, and is about 14 miles (22 km) wide.

Whatever projectile hit Devon Island, it was about a kilometer (0.6 mi) in diameter and was launching at cosmic speeds. At the moment of collision, it delivered a pulse of energy equivalent to 100 million kilotons of TNT. The impact wiped out almost all life for several hundred kilometers and flattened the landscape.

After the dust settled, what was left was a smoking hole, which became Haughton Crater.

It is full of canyons, valleys and ravines. This “patterned ground” is covered with ice that routinely thaws and refreezes.

The crater floor has suffered very little erosion due to lack of rain, as has the surface of the Moon.

These factors make the crater an ideal practice terrain to emulate an interplanetary expedition.

Recent images of Mars sent to Earth by the Perseverance rover in March 2024 show a marked resemblance to the lifeless landscape of Devon Island.

Every summer, the Haughton-Mars Project (HMP), a collaboration between NASA, the Seti Institute, and the Mars Institute, takes advantage of otherworldly topography to conduct its experiments.

Their base camp is located on the edge of the Haughton Impact Center. All supplies must arrive by air.

Geologists and biologists investigate this “polar desert” (a very cold, very dry expanse) to compare the rocks and microbial life forms with what we know about the Moon, Mars and other planetary bodies.

Astronautical explorers and engineers develop exploration technologies.

For example, Mars has a thin atmosphere and, as expected, no dedicated runways for landing aerial vehicles. A thin atmosphere makes it difficult for spacecraft to “take off,” while rugged, undulating geology makes it difficult for them to land.

Consequently, HMP has been working on remote-controlled vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) vehicles: light aircraft that can take off in adverse atmospheres and land on rocky terrain. The strange terrain and strong winds that buffet the crater make it ideal for testing these aircraft.

Other space technology they have tested includes robotic vehicles, drills, life support systems, plant growth systems and conceptual space suits.

The latter is particularly crucial.

One of the critical elements that will make it easier for humans to walk on Mars is a spacesuit designed to cope with its brutal environment: the thin atmosphere is a cloud of carbon dioxide, nitrogen and argon gases. Arnold Schwarzenegger asphyxiating when exposed to the planet’s atmosphere in the late 1990s Total Recall is surprisingly accurate.

Additionally, the oxidized dust particles that give the planet its characteristic reddish hue frequently turn into violent dust storms.

A spacesuit would have to be able to withstand these violent elements if people were to survive on the surface of Mars. Hence the extensive spacesuit testing at Haughton Crater.

A researcher carrying out a simulation in Haughton Crater, Devon Island. NASA technicians simulate possible mission emergencies in a desolate place

Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station. The habitat is used by ad hoc scientists and researchers.

Devon Island is also home to the Flashline Mars Arctic research station, which also serves as an analogue for Mars. Started by the Mars Society, a nonprofit volunteer organization, the habitat is now used by scientists and researchers on an ad hoc basis, many of whom work for NASA or similar international space programs.

Previous research conducted at FMARS includes tests of ‘low-level laser light therapy’, used to keep astronauts flexible and agile when exposed to cold temperatures for long periods of time. Despite glowing red, Mars is unimaginably cold: -60 degrees Celsius on average, down to -160°C at the planet’s polar caps.

FMARS also practices “Crew Safety in Simulated Emergency Situations.”

A polar bear hunting narwhals and beluga whales off the coast of Devon Island

Impressive: the northeast coast of Devon Island is an area full of glaciers and fjords

From Greenland it is possible to sail to Devon Island following the path of the legendary Northwest Passage.

In these, NASA technicians simulate possible mission emergencies, such as toxic chemical leaks, EVA suit leaks, power outages, habitat depressurization, habitat fires, power outages or medical emergencies, to develop contingencies for face them.

In a documentary about the Devon Island projects called ‘Passage to Mars’, scientists noted that if their experiences on the island are anything to go by, ‘only the most resilient explorers will thrive on the Red Planet.’

May I visit?

Tourists venture to Devon Island.

From Greenland it is possible to sail there following the path of the legendary Northwest Passage, a journey that many European explorers undertook in the 19th century in the hope of finding a direct route to mainland China (they failed).

However, instead of heading to the crater, travelers usually head to the Truelove Lowlands area, on the northeast coast, an area full of glaciers and fjords, impressive frozen landscapes that look nothing like Mars.

Comparatively warm (two to eight degrees Celsius in summer), with some vegetation, musk oxen, waterfowl and wandering lemmings graze in this area.

In the coastal seas surrounding the island you can spot narwhals and beluga whales.

It’s not Life on Mars, but these magnificent creatures are otherworldly in their own right.