Alfred Wainwright once compared Coniston in the southern Lake District with Zermatt in the Swiss Alps, saying that each seemed to have a particularly strong affinity with its nearest mountains.

Well, the Old Man of Coniston may rise to a mere 2,635 feet, while Zermatt’s Matterhorn rises to 14,692 feet, but there is an element of truth in the great hiking scribe’s fantastic comparison.

The town of Coniston, population 928, somehow feels like it belongs on its mountain.

This close connection has a long history, and industry provides the glue.

For many years, copper and slate were mined on the eastern slopes of the Old Man, from the time of Elizabeth I, when the first copper mines were established, with German miners sent there.

Benevolent Giant: Tom Chesshyre travels to the Lake District town of Coniston. Above, the old man of Coniston and Coniston Water

Tom stayed in a ‘mountain cabin’ (pictured) in Coppermines Valley, which sits above the village of Coniston.

These Germans turned out to be more than just hands working the copper veins. They are also believed to have introduced the local sausage recipes that would eventually become known as Cumberlands.

Whatever the truth of this, copper mining began in the 1560s and continued until the 1950s.

Slate is still quarried and it is possible to buy beautiful silver-green slabs at Coniston Stonecraft, a workshop on the road leading to the Old Man behind the Sun Hotel.

This hidden business is located in the old copper ore and slate railway warehouse buildings; The tracks used to end at Broughton-in-Furness.

Meanwhile, the Sun Hotel was where Donald Campbell is believed to have spent the night before his fatal crash at almost 300mph on Bluebird K7 during his attempt to break the world water speed record at Coniston Water in 1967.

Alfred Wainwright once compared Coniston (pictured) to Zermatt in the Swiss Alps, reveals Tom

The Old Man of Coniston has seen copper and slate mining activity since the days of Elizabeth I. Above, an abandoned slate mine on the mountain

LEFT: A “mountain cabin” type jacuzzi. RIGHT: Tom felt “safe and sound” in his Coppermines Valley rental apartment

You can learn all about it at the Ruskin Museum, just off the main street, close to the bubbling water of Church Beck and a busy cluster of inns that mark the center of the town at a junction next to a bridge.

There is a smashed piece of the ill-fated ship at the rear in a special section by Donald Campbell.

The museum’s name comes from another historical ghost: John Ruskin, the social reformer and essayist (1819-1900), who loved the local landscape so much that he bought a mansion on the other side of Coniston Water.

This building, called Brantwood (about a 45-minute walk along the lake from the village), is open to the public and offers an intriguing insight into Ruskin’s somewhat peculiar life.

Tom said the holiday home and its crackling fireplace “seemed a long way from anywhere in Britain’s ‘Swiss Alps'”. In the photo: the living room of one of the cabins.

During his trip, Tom visits the Ruskin Museum, a “rich source of local history.”

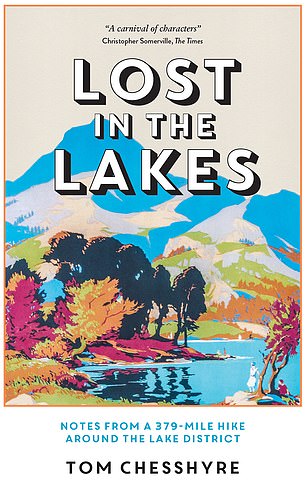

Tom is the author of Lost In The Lakes: notes from a 379-mile walk through the Lake District.

The Ruskin Museum is a rich source of local history. The root of the name Coniston dates back to the Old Norse Konigs Tun (king’s settlement), in reference to a Viking king called Thorstein.

The exhibits also capture the early days of mountaineering and the Fell & Rock Climbing Club, founded in 1906 and based in Coniston.

It would be rude, if we are fit and the weather is good, not to climb the Old Man. This I did, enjoying panoramic views across the sparkling lakes to the Irish Sea and south to Morecambe Bay.

I then went down to the village and had a pint of Bluebird beer in the quaint Black Bull pub.

I was in good historical company. The poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge recorded that he had “dined oatcake and cheese, with a pint of ale and two glasses of rum and water sweetened with preserved currants” at the nearby Blacksmiths Arms, Broughton Mills, during his own excursion around the Lakes in 1802.

Back at my holiday home in Coppermines Valley, with the fire roaring, I felt a long way from anywhere in Britain’s “Swiss Alps”, safe and sound with the “benevolent giant” (in Wainwright’s words) of the Old Man looming above.