<!–

<!–

<!– <!–

<!–

<!–

<!–

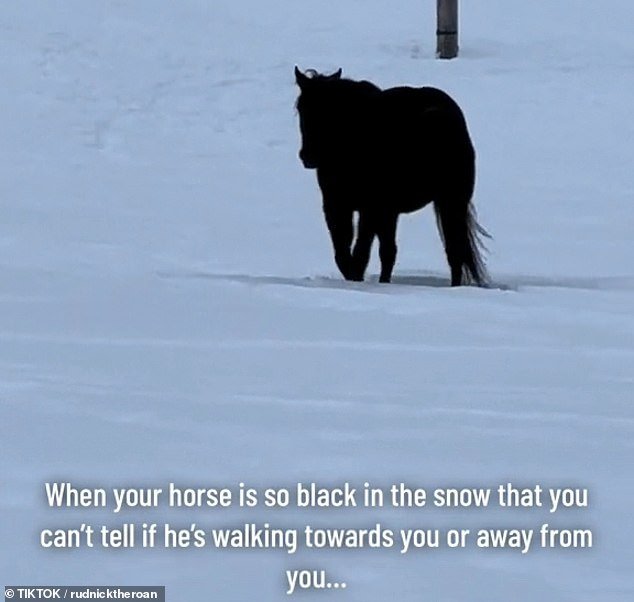

A black horse walking in the snow has inadvertently become a viral optical illusion, with the stallion cutting such a sharp silhouette against the white background that it’s difficult to see if the majestic animal is walking towards or away from the camera.

Alesia Carrie is the owner of Rudnik, a horse who sports a roan-patterned coat, and the couple lives in Kamloops, British Columbia.

In January, Alesia shared a 40-second video of Rudnik taking a walk some distance away from her in a field, with a thick layer of fresh snow covering the ground.

As Alesia observed in the superimposed text, her horse looked “so black in the snow that you can’t tell if it’s walking toward you or away from you.”

Rudnik, a black horse from Kamloops, British Columbia, surprised the Internet with an innocent walk through the snow.

His owner, Alesia Carrie, captured him jogging through a snowy landscape in a 40-second video, and the clip inadvertently became a viral optical illusion on TikTok.

No one could agree on whether Rudnik was walking toward or away from the camera, with the silhouette of his head and tail blending perfectly with that of his body.

Alesia commented on the clip that Rudnik is “so black in the snow that you can’t tell if he’s walking towards you or away from you.”

In fact, in the video, it’s virtually impossible to say with certainty whether Rudnik is trotting diagonally toward Alesia or away from her, with the outline of his head and tail blending perfectly with that of his torso and flank.

On top of that, whether due to cloud cover or the time of day, the natural light in the clip is dim and gray, erasing any trace of shadows that might otherwise have revealed its changing position in the landscape.

Additionally, he is far enough away from Alesia that it cannot be determined whether he is getting smaller or larger as he moves in the video.

In the final seconds of the footage, Rudnik pauses and stands majestically, surveying his snow-covered domain.

The post has since gone viral on TikTok, racking up over 16 million views and over 2.2 million likes, and has even gotten a reshare on LADBible.

More than 11,000 viewers flocked to the comments of Alesia’s original post to debate which direction Rudnik had been walking in real life.

Thousands took to the comments to admit their bewilderment at the ambiguous image.

“I was like you, obviously, and then my brain skipped a beat,” wrote one confident and confused fan.

“I said yes, you can… wait, what,” a second repeated.

“It literally kept going back and forth for me…that was weird,” a third agreed.

‘OMG I can literally see both?!?!?!?!’ a fourth was scared.

“I can flip the horse, it’s like that brain puzzle in real life,” observed a fifth.

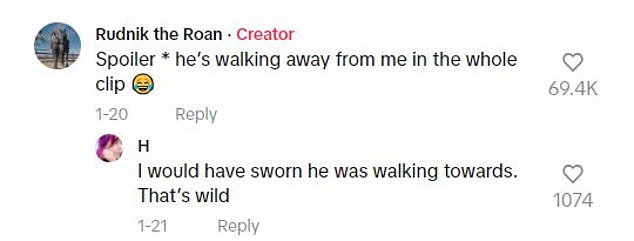

But Alesia put an end to the entire discussion with a follow-up comment on her original post.

Alesia finally revealed the truth: Rudnik had been “pulling away” from her during “the entire clip”

“Spoiler* he is walking away from me throughout the clip,” she declared.

‘I could have sworn I was walking towards. “That’s crazy,” confessed an astonished voyeur.

‘I REFUSE TO BELIEVE THIS,’ someone else exclaimed.

And, with Alesia’s admission, at least one cocky brother was right about the matter: “I showed it to my brother and we had a little discussion about the direction and showing him this comment was pure satisfaction.”