Meghan Markle’s former Suits co-star has revealed there was a “really terrible and disgusting” smell during her wedding to Prince Harry.

Rick Hoffman, who played Louis Marlowe Litt in the American legal drama, went viral in 2018, after photos of him with a disgusted expression during Megan and Harry’s ceremony took over the web.

Now the actor, 53, has opened up about what was making him look so uncomfortable and said it was due to a horrible smell in the air.

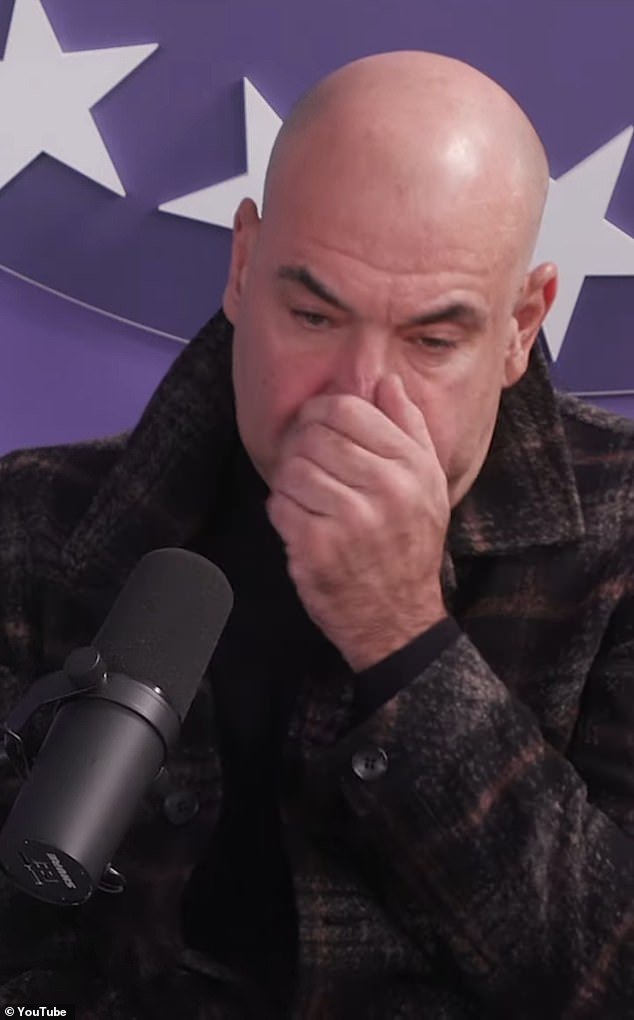

During a recent appearance on the Chicks in the Office podcast, Rick joked, “If you type my name into Google, you’ll see [me] making that horrible face.

Meghan Markle’s former Suits co-star has revealed there was a “really terrible, disgusting” smell during her wedding to Prince Harry.

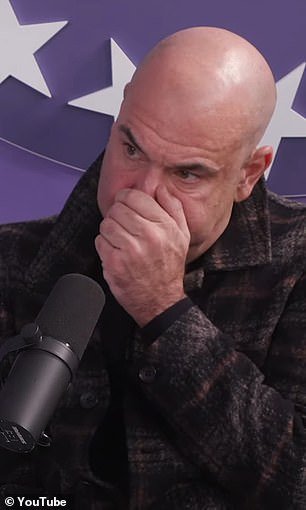

Rick Hoffman went viral in 2018, after photos of him with a disgusted expression during Megan and Harry’s ceremony took over the web. He was seen with Meghan in 2011.

Now the actor, 53, has opened up about what was making him look so uncomfortable and said it was due to a horrible smell in the air. He is seen at the wedding.

While talking about his expression, he explained that shortly after sitting down he “started to smell something really terrible and disgusting.”

While at first he thought someone near him “had terrible breath,” he eventually realized it was coming from “more than one person.”

“I’m starting to get a little nervous because it bothers me and I’m very sensitive when it comes to that,” he recalled.

‘[The ceremony] It’s an hour and a half and [the smell] It comes constantly to me now. She’s entering my body.’

Because he’s “so particular about hygiene,” Rick said he was worried people would think it was coming from him, so he asked his fellow Suits stars, “Do you smell that?”

And they say, “No.” So now I’m literally alone on an island and I’m just like, ‘Motherfucker,'” she continued. ‘And that is [the expression] They got [on camera that went viral].’

Rick added that of everyone on the show, Meghan laughed at him the most for his “issues” when it came to “other people’s hygiene.”

‘She always knew and always laughed at how sensitive I was. It was very ironic,” she concluded.

During a recent appearance on the Chicks in the Office podcast, Rick joked, “If you type my name into Google, you’ll see [me] making that horrible face’

While talking about his expression, he explained that shortly after sitting down he “started to smell something really terrible and disgusting.”

While at first he thought someone near him “had terrible breath,” he eventually realized it was coming from “more than one person.” Meghan and Harry are seen at the wedding

Rick starred alongside the Duchess of Sussex from 2011 until she left the series in 2017, following her engagement to Prince Harry. He continued as Louis for two more seasons after his departure.

Last summer, the legal drama unexpectedly became the most-watched show in the United States for 12 straight weeks after joining Netflix.

Because he’s “so particular about hygiene,” Rick said he was worried people would think it was coming from him, so he asked his fellow Suits stars, “Do you smell that?” He is seen arriving at the wedding.

Last month news hit the web that Suits was getting a new spin-off series, titled Suits: LA.

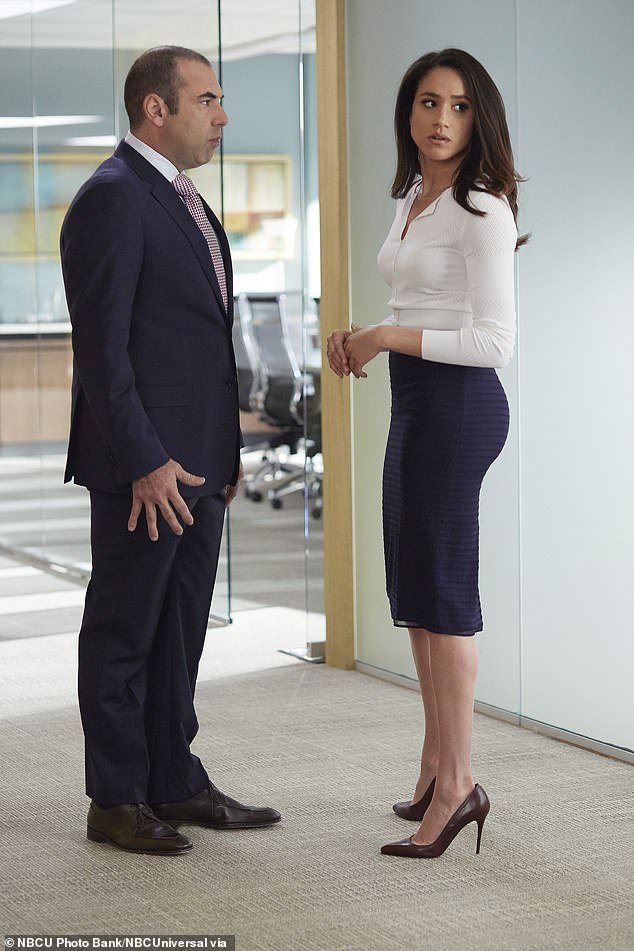

Set in the same world as the original series but with completely new characters, the series will follow a former New York federal prosecutor named Ted Black, played by Stephen Amell, who has reinvented himself by representing the most powerful clients in Los Angeles.

A synopsis reads: “His company is at a crisis point, and to survive he must accept a role he has despised his entire career.

‘Ted is surrounded by an all-star group of characters who test his loyalty to Ted and each other as they can’t help but mix their personal and professional lives.

“All of this happens as the events of years ago that led Ted to leave everything and everyone he loved behind slowly unravel.”

Original Suits creator Aaron Korsh has returned to develop the new series, serving as writer and executive producer alongside David Bartis and Dog Liman for Hypnotic and Gene Klein. Production is scheduled to begin in Vancouver at the end of March, according to Variety.

And they say, “No.” So now I’m literally alone on an island,” she continued. ‘And that’s [the expression] They got [on camera that went viral]’

Rick added that of everyone on the show, Meghan laughed at him the most for his “issues” when it came to “other people’s hygiene.”

Last summer, the legal drama unexpectedly became the most-watched show in the US for 12 straight weeks after its addition to Netflix.

A source told DailyMail.com earlier this month that Meghan will not appear in the new show, but she did try to involve her company Archewell in the production.

‘Meghan was clear that she did not want to get involved as an actress. But Archewell was trying to make her way as a producer on the spin-off,” they stated. “NBC has killed that idea.”

However, separate sources close to Archewell strongly denied this and said the company would never have been involved in a reboot.

Many members of the original cast have reunited in recent months, but Meghan was noticeably absent from all of the reunions.

Patrick J. Adams, Gina Torres, Sarah Rafferty and Gabriel Macht were spotted together on the Golden Globes red carpet in January.

During the awards show, Gina made a shocking admission about her relationship with the Duchess during the event.

Last month news hit the web that Suits was getting a new spin-off series, titled Suits: LA. It will star Stephen Amell (seen)

Many of the original Suits stars reunited at the Golden Globes in January, including Patrick J. Adams, Gina Torres, Sarah Rafferty and Gabriel Macht.

Additionally, Gina, Sarah and Rick reunited for an Elf commercial at the Super Bowl, but Meghan was noticeably absent from both meetings.

She admitted: ‘We don’t have his number. We just don’t do it,” and she added that the rest of the cast stayed in touch via a WhatsApp group.

Additionally, Gina, Sarah and Rick reunited for an Elf commercial at the Super Bowl.

While chatting with People In this regard, Rick said that working with his former co-stars again was “the ultimate happiness,” while Sarah described it as “coming home.”

They added that Patrick couldn’t appear in the commercial because he was busy “filming a movie in South Africa,” but they didn’t mention Meghan.

Patrick and Gabriel also said The Hollywood Reporter that they have had “zero communication” with their former co-star Meghan.

Meghan reacted to the revival of her show late last year, saying Variety that he had “no idea” what caused it, but added: “Good shows are eternal.”

“It’s hard to find a show you can watch that many episodes these days,” he said at the time. “So that might have something to do with it.”