Sam Cansfield was sitting at her desk drinking coffee when she suddenly felt a crushing pressure on her chest.

The sensation took Sam, 54, fit and healthy, by surprise, but as the effect “was quite short-lived”, he didn’t think more about it.

But mysteriously over the next two weeks it happened again and again, and Sam developed a tingling sensation in his throat and also a runny nose, even though he didn’t have a cold.

“It was a very strange feeling and I didn’t know what was causing it,” Sam remembers.

From time to time he also felt like he had a lump in his throat and sometimes he even felt like he was drowning.

After three weeks, Sam, who works on a property and lives near Hertford, saw her GP who sent her for an EKG, suspecting a problem with her heart rhythm.

Sam Cansfield, a fit and healthy 54-year-old woman, developed a tingling sensation in her throat and also had a runny nose, although she did not have a cold.

When everything became clear, the GP offered no further tests.

“At the time I was really worried as no one seemed to know what the problem was,” Sam says.

‘But all the time, the pressure in my chest, the runny nose and the strange tingling sensation in my throat were getting worse.

‘The symptoms got worse after eating anything, every time I drank coffee. But she was there in some form all the time.”

Worried that something was seriously wrong, in November 2020 Sam made an appointment with a private GP online, who identified the problem as a form of reflux, which surprised Sam, “as I didn’t have the typical symptoms of reflux.” “, says.

There was a reason for that: I didn’t have typical reflux.

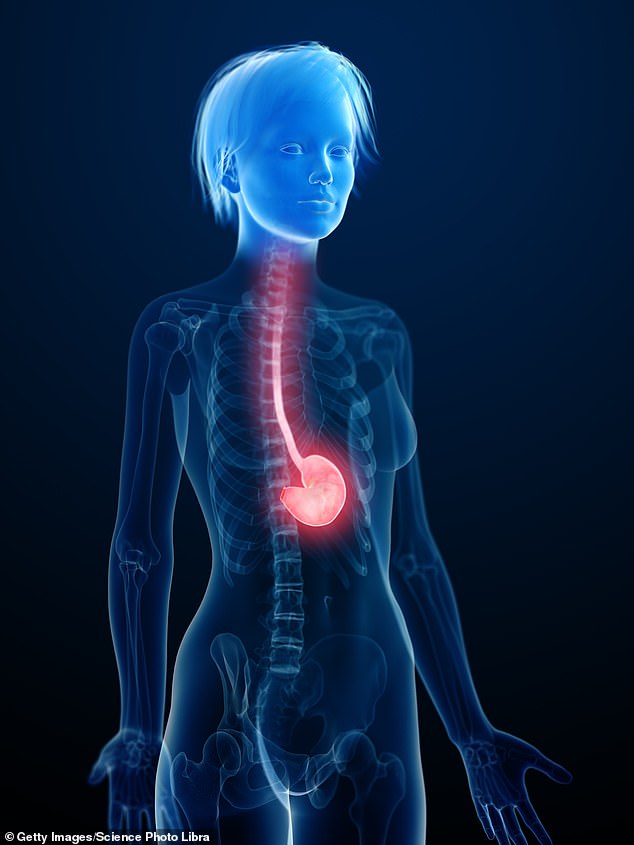

Reflux normally occurs when the acidic contents of the stomach leak into the esophagus, usually causing heartburn (a burning sensation in the chest) and nausea, but Sam had what is known as silent reflux.

Also called laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR), it causes symptoms centered in the throat, nose, and chest, such as coughing, sore throat, needing to constantly clear your throat, or feeling like you have a lump in your throat.

Silent reflux, like all reflux, begins when the valve between the stomach and the bottom of the esophagus (the esophagus) weakens, allowing powerful acids and other stomach contents to escape.

Risk factors include being overweight, as this can put pressure on the stomach valve, or smoking, a hernia (where part of the stomach pushes into the chest) and suffering from stress and anxiety.

Diet can also contribute to reflux, as certain foods and drinks, such as coffee, tomatoes, alcohol, chocolate, and fatty or spicy foods, can cause excess stomach acid to be produced and cause the valve to become clogged. relax.

But there may be no obvious reason why it develops, according to the NHS.

It is not fully understood why some patients experience silent symptoms while others have a more classic heartburn sensation.

One theory is that irritating substances escape from the stomach suspended in an aerosol, rather than the rush of liquid acid that typically causes heartburn, says Nick Boyle, an upper gastrointestinal surgeon and medical director at Reflux UK, a specialist private clinic with centers in all over the UK.

This aerosol can travel down the esophagus and reach the throat, larynx, the back of the mouth and even the sinuses behind the nose to create a wide range of symptoms, Boyle says.

Some patients develop a hoarse or weak voice because the acid irritates their larynx, or some suffer from sinus problems, a runny nose, and an unpleasant taste in the mouth.

Because stomach spray can be inhaled and reach the lungs, in some cases the condition can lead to persistent respiratory infections.

“It’s called silent reflux because it doesn’t accompany heartburn, but I’ve always thought it’s not a good name,” says Mr Boyle.

“A lot of people have these symptoms and it’s not silent, it worries them a lot.”

Although one in four people in the UK suffer from some form of reflux, according to the charity Gut UK, silent reflux is not recorded separately from other types.

However, a UK study of nearly 380 randomly selected people, published in the European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology in 2012, found that one in three had symptoms of silent reflux.

The problem is that, in the absence of heartburn, many people with silent reflux struggle for years without a diagnosis, Boyle says.

Dr Rehan Haidry, consultant gastroenterologist at the private Cleveland Clinic in London, says around 10 per cent of his patients with reflux have the silent form and some of them will have been wrongly told they had asthma.

But a prompt diagnosis is important as any form of reflux increases the risk of Barrett’s esophagus, where the cells in the lining of the esophagus undergo changes as a result of constant exposure to acid.

And up to 13 percent of people with Barrett’s esophagus will develop esophageal cancer, according to Cancer Research UK, which is why people with it are monitored for signs of cancer.

Reflux is often diagnosed simply by a doctor taking a history of symptoms, but if the diagnosis is in doubt, some may be referred for a gastroscopy, where a small camera is placed in the throat to examine the esophagus and stomach.

If silent reflux is suspected, another test that may be performed involves inserting a small capsule into the esophagus (through a small tube, called a catheter), which remains in place for 24 hours to measure pH levels, which monitors wirelessly. . Low pH could be a sign of acid.

After surgery, Sam can go back to eating whatever he wants and even drinking coffee, which once exacerbated his symptoms.

Whatever the form of reflux, the treatment is the same.

It starts with lifestyle changes, such as losing weight if necessary and taking antacids, which neutralize stomach acid to prevent it from irritating the lining of the esophagus.

Another option is alginates, which come in liquid and tablet form and form a protective barrier over stomach contents to prevent them from rising into the esophagus.

“We use Gaviscon Advance liquid a lot, which is an alginate, and have found it works well for many patients,” says Mr Boyle.

Patients may also be prescribed medications called proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which help reduce stomach acid production.

However, these tend to be less effective for silent reflux, since in this case it is not just stomach acid that causes the problem: several different substances found in the stomach (including bile and pepsin, a stomach enzyme) contribute to it. .

(These substances are also involved in other forms of reflux, but seem particularly important in LPR, for reasons that are not fully understood.)

“PPIs only work for about 20 per cent of people with silent reflux,” says Mr Boyle.

“And many doctors have the misconception that if PPIs don’t work, then it’s not reflux.”

If people with silent reflux do not improve on PPIs after six weeks, then they should be stopped, Boyle says.

He adds that patients are often switched to higher doses or different PPIs; However, these are unlikely to work and could actually make the problem worse, as the medications suppress acid production, which can lead to an overgrowth of bacteria, called small intestine bacteria. excessive growth (SIBO), which can cause bloating and belching, and even worsening reflux.

Tests showed that Sam also had excessive stomach acid production due to triggers like coffee.

During surgery, it was also discovered that Sam had a hernia that weakened the valve at the top of his stomach; His stomach pushed into his chest.

After Sam’s diagnosis in November 2020, he tried a PPI and another type of medication that reduces acid production, called an H2 blocker, but neither worked.

She eliminated tea, coffee and high-fat foods and tried not to eat too close to bedtime and slept sitting up, propped up with pillows, to stop reflux while she slept.

“My symptoms, including chest pressure and runny nose, continued despite everything I tried, and I lived on a diet of antacids, drinking bottles and bottles of Gaviscon,” he says.

“I was practically drinking it for months, taking it after everything I ate.”

Risk factors include being overweight, as this can put pressure on the stomach valve, or smoking, a hernia (where part of the stomach pushes into the chest) and suffering from stress and anxiety.

As the symptoms persisted, Sam decided he needed a different approach.

‘It was just a horrible experience and I wanted it to be dealt with properly. So, even though it seemed like a big step, I decided to go ahead with the surgery.”

It is usually reserved for serious cases that do not respond to other measures.

This usually takes the form of an operation called fundoplication, where minimally invasive surgery is used to wrap the upper part of the stomach around the lower part of the esophagus to tighten the valve and prevent stomach contents from leaking.

Sam had a newer procedure performed privately by Dr. Haidry, called incisionless transoral fundoplication, which is performed with instruments and a camera inserted through the throat, making it less invasive.

The esophagus is pushed into the upper part of the stomach, where it is sutured and stitched into place. Studies show that this creates a new, stronger valve between the stomach and throat, to stop the return of acid, although there is a small risk of side effects such as difficulty burping, swallowing and bloating.

Other newer options for surgery include using a small band of magnets around the base of the esophagus, just above the stomach, to strengthen the valve.

It took Sam a year to fully recover from the operation in the summer of 2021, but the effects have been transformative.

“I no longer have symptoms: I can drink coffee and eat whatever I want,” he says.

‘I don’t worry about going to sleep or being woken up by my symptoms, and I can go back to sleep lying down, rather than lying on cushions.

‘It has changed my life.’