Today, the ruined city of Chichén Itzá in Mexico is a major tourist attraction, attracting around two million people from around the world each year.

The impressive ancient buildings of Chichén Itzá, including the famous El Castillo pyramid, nearly 100 feet tall, are a testament to the skill of the Mayan people.

But the ancient city hides a horrifying secret: the Mayans practiced brutal ritual murders of children to appease the gods about 1,000 years ago.

A new study of skeletal remains found at the site has revealed that their victims were children between the ages of 3 and 6, some of whom were twins.

As part of a bloody public event, the children were reportedly massacred with knives, spears or axes before their bodies were placed in an underground storage chamber.

The Castle, also known as the Temple of Kukulcán, is among the largest structures in Chichén Itzá, Mexico’s ancient ruined city.

A full-scale stone representation of a huge tzompantli (skull rack) at the central point of the sacrificial site at Chichén Itzá.

The study was led by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

Chichen Itza is one of the New 7 Wonders of the World, but it was once a prosperous city, originally built by the Mayans about 1,500 years ago.

The Mayans participated in the brutal act of human sacrifice because they believed that blood was a powerful source of food for their gods and that in return they would obtain rain and fertile fields.

Chichén Itzá is already known for ritual killings, evident by the remains of sacrificed people and art, including ‘tzompantli’ (stone carvings of skulls).

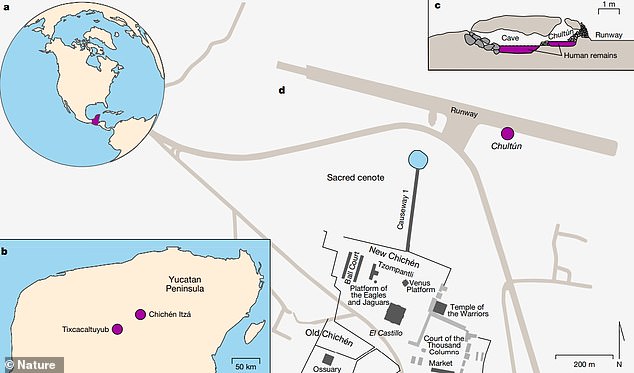

In 1967 the remains of more than 100 young children were found in a ‘chultún’ (a bottle-shaped chamber designed for underground storage) at Chichén Itzá.

These underground elements were considered at that time points of connection with the underworld, the supernatural world of the dead.

For their new study, the researchers conducted genetic analyzes of the remains of 64 of these individuals to reveal their sex.

“When we analyze the genome, there are regions that are part of the Y chromosome, which is found only in male individuals,” study author Rodrigo Barquera, from the Max Planck Institute, told MailOnline.

“So if we find those regions as part of our genetic data, we can say with confidence that the sex of that individual is male.”

Chichen Itza is a popular tourist site today and one of the New 7 Wonders of the World, but it was once a prosperous city, originally built by the Mayans about 1,500 years ago.

The sculpture in the Great Ball Court of Chichén Itzá represents sacrifice by decapitation. The figure on the left holds the severed head of the figure on the right, who spews blood in the form of snakes from his neck.

Until now, there was a widespread belief among scholars that mainly women were sacrificed at Chichén Itzá.

This is largely due to early 20th century stories that popularized “dark tales” of young women and girls as victims.

But the new genetic analysis unexpectedly shows “with certainty” that all 64 individuals analyzed were boys, and includes two sets of identical twins.

“Since these twins occur spontaneously in only 0.4 percent of the general population, the presence of two pairs of identical twins in the chultun is much higher than would be expected by chance,” the authors note.

In fact, the results suggest that at least a quarter of the children were closely related to at least one other child in the chultún.

The Mayans might have somehow considered their “close biological kinship” a better offering to the gods.

Twins are especially “auspicious” in Mayan mythology and the sacrifice of twins is a central theme in the sacred Book of the K’iche’ Mayan Council, the ‘Popol Vuh’.

Portion of reconstructed stone tzompantli, or skull rack, at Chichén Itzá. These are carvings on the walls; there are no skulls inside the stone

In 1967, the remains of more than 100 young children were found in a ‘chultún’, a bottle-shaped chamber designed for underground storage.

What’s more, these young victims – all from local Mayan populations – had consumed similar diets, the analysis shows, suggesting they were raised in the same household.

They were probably murdered as part of twisted public spectacles before their bodies were placed in the chultún.

Dating of the remains also revealed that the chultún was used for mortuary purposes for more than 500 years, from 600 to 1100 AD.

Most of them were killed and buried during the 200-year period of Chichen Itza’s ‘political peak’, between 800 and 1000 AD.

The Mayan civilization, which originated around 2600 BC. C., prospered in Central America for almost 3000 years and reached its peak between 250 and 900 AD. c.

Noted for the only fully developed written language of pre-Columbian America, the Mayans had advanced art and architecture, as well as mathematical and astronomical systems.

But the findings provide the best information yet about the poor young victims who died at the hands of their aberrant rituals.

The study – ‘Ancient genomes reveal knowledge about ritual life in Chichén Itzá’ – is published today in the journal Nature.