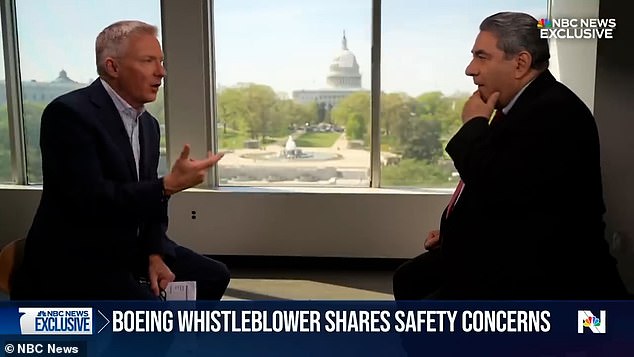

Boeing whistleblower Sam Salehpour told NBC News’ Tom Costello in a shocking interview that Boeing’s controversial 787 planes should remain grounded due to “fatal defects” that could cause the plane to break up in mid-air.

The interview, which aired Tuesday night, comes just a day before Salehpour is scheduled to address Congress to testify about his concerns surrounding Boeing’s safety practices, particularly fatigue cracks as a result. of airplanes flying thousands of hours.

Salehpour said that by appearing in the media and in front of Congress, he was going to save people’s lives. Boeing CEO Dave Calhoun has also been summoned, but it is not yet clear if he will attend.

This week, Steve Chisholm, Boeing’s chief mechanical and structural engineering engineer, said researchers have not found fatigue cracks in in-service 787 planes that have undergone intensive maintenance.

The pair are set to answer questions about a series of safety incidents involving Boeing, notably the explosion of a door attachment that occurred on an Alaska Airlines flight in January.

The panel covered a space left for an additional emergency door on the plane, operated by Alaska Airlines. The pilots were able to land safely and there were no injuries.

Earlier this year, the veteran engineer laid out his allegations in a Federal Aviation Administration complaint.

The interview, which aired Tuesday night, comes just one day before Sam Salehpour is scheduled to address Congress to testify about his concerns about Boeing’s safety practices.

Salehpour said he believes the stress caused by the aggressive fastening of parts could cause a plane to fall apart in the air.

Salehpour previously said that instead of taking his problems seriously, Boeing retaliated against him, something the company denies.

A door plug exploded midair on an Alaska Airlines flight on January 7, 2024 in Portland, Oregon.

Pictured: Outgoing Boeing CEO David Calhoun speaking to reporters weeks after a Boeing 737 door plug exploded.

Salehpour told Costello that the stress created by joining large pieces of the fuselage together, to fix gaps, could cause a “fatigue failure” in the air.

The result would be that “the plane falls apart at the joints… once you fall apart, you will descend to the ground.” When asked if he felt the plane might fall apart in mid-air, Salehpour responded: “Absolutely.”

“As far as I’m concerned, the entire world fleet needs attention right now,” he continued, referring to the 787.

“And the note is that you need to check for loopholes and make sure there’s no chance of premature failure,” Salehpour continued.

In addition to his structural concerns, Salehpour said he faced retaliation, including threats and exclusion from meetings, after identifying engineering problems that affected the structural integrity of the planes, and claimed that Boeing used shortcuts to reduce bottlenecks during assembly. of the 787, his lawyers said. .

Boeing halted deliveries of the 787 widebody aircraft for more than a year, until August 2022, while the FAA investigated quality issues and manufacturing defects.

In 2021, Boeing said it had shims that were not the right size and that some planes had areas that did not meet skin flatness specifications. A shim is a thin piece of material used to fill small gaps in a manufactured product.

Pictured: Boeing whistleblower John Barnett, who was found dead in March after an apparent suicide.

Salehpour observed shortcuts used by Boeing to reduce bottlenecks during the 787 assembly process that led to “excessive stress on major airplane joints and drilling debris embedded between key joints in more than 1,000 airplanes,” his attorneys said. .

Last week he told reporters that he saw misalignment problems in the production of the 777 wide-body aircraft that were resolved through the use of force.

“I literally saw people jumping on pieces of the plane to line them up,” he said.

Two senior Boeing officials said Monday that there were no findings of fuselage fatigue among the nearly 700 Dreamliner planes in service that have undergone extensive maintenance inspections after six and 12 years.

“All of these results have been shared with the FAA,” said Steve Chisholm.

The 787, which was launched in 2004, had a clearance specification of five thousandths of an inch within a five-inch area, or “the thickness of a human hair,” said Lisa Fahl, vice president of aircraft programs at Boeing Commercial Airplanes. . engineering.

He said reports of workers jumping on airplane parts “were not part of our process.”

Salehpour’s lawyer, Debra Katz, said in a statement emailed to Reuters that her client tried for years to see data that addressed her concerns about the safety of the 787 breaches.

“Any information provided by Boeing must be validated by independent experts and the FAA before it is taken at face value,” Katz said.

The Federal Aviation Administration has also been investigating Salehpour’s allegations since February, according to the subcommittee.

Salehpour, whose concerns were outlined in a New York Times article last week, he was also expected to describe the retaliation he faced after raising his concerns.

According to that account, Salehpour worked on the 787 but became alarmed by changes in the assembly of the fuselage, the main body of the plane.

That process involves assembling and fastening giant sections of the fuselage, each produced by a different company, according to Salehpour’s account.

Salehpour told the Times that he believed Boeing was taking shortcuts that led to excessive force in the assembly process, creating warps in the composite material used in the plane’s outer skin.

These composites typically consist of layers of plastic reinforced by a mesh of carbon or glass fibers, which increases tensile strength and makes them a useful substitute for heavier metals.

But composites can lose those benefits if they become twisted or otherwise deformed. Salehpour alleged that such problems could create increased material fatigue, possibly leading to premature failure of the composite, according to the Times report.

Accident investigators’ subsequent discovery of missing bolts intended to secure the door panel in January shook Boeing, which once boasted an enviable safety culture.

Alaska Airlines and United Airlines, the two U.S. airlines that fly the Max 9, also reported finding loose bolts and other hardware on other panels, suggesting that quality problems with the door plugs were not limited to a single plane. .

Both the 787 and 737 Max have been plagued by production defects that sporadically delayed deliveries and left airlines without planes during busy travel seasons.