The German dynasty behind the Leibniz biscuit empire has admitted its Nazi past after historians revealed the company’s widespread use of forced labour and financial support for Hitler’s regime during World War II.

The Bahlsen family has led the brand behind the iconic biscuits since it was founded by Hermann Bahlsen in 1891, and has now said it had never asked itself “the obvious question of how our company was able to survive during World War II”.

The biscuit maker came under increasing pressure to address its dark past in 2019 when Verena Bahlsen, daughter of owner Werner M Bahlsen, sparked outrage by suggesting the company had “done nothing wrong” and treated forced labourers “well”.

Critics attacked the wealthy heiress, who later apologized and the family pledged to investigate the company’s history surrounding the world wars.

The report by historians Manfred Grieger and Hartmut Berghoff of the University of Göttingen reveals that the use of forced labour was more extensive than previously thought.

Verena Bahlsen (left) is one of four children of company owner Werner Bahlsen (right).

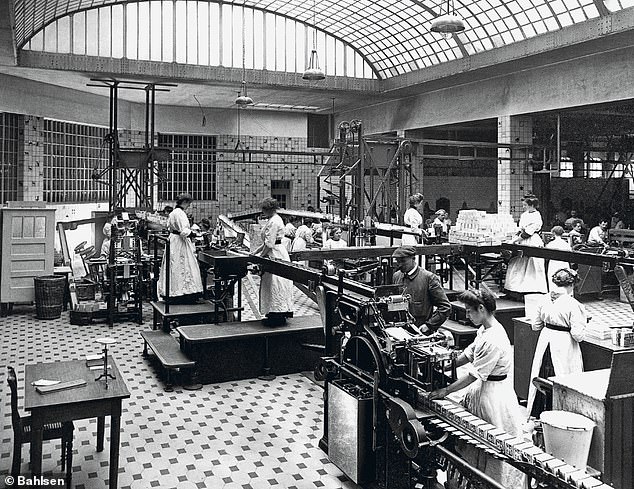

The majority of forced labourers at Hanover-based Bahlsen were women, many of them from Nazi-occupied Poland and Ukraine. Pictured: The Bahlsen production line in Germany in the 1930s

The Bahlsen family has led the company behind the iconic Leibniz biscuits for over 130 years.

They found that the company employed about 800 foreign workers between 1940 and 1945, up from previous estimates of around 200.

The majority of forced laborers at Hanover-based Bahlsen were women, many of them from Nazi-occupied Poland and Ukraine.

This was common in Germany’s factories during the war, where an estimated 13 million people from the occupied territories were forced into labor to mitigate the loss of labor force.

Foreign workers were subjected to racial discrimination and harsh treatment, the report found.

They received lower wages, limited food rations and poorer medical care than other workers.

Polish women were required to wear a purple and yellow P badge to indicate their nationality, and social contact with Germans was prohibited.

They were housed in barracks away from the locals and threatened with execution any Polish men who had sexual contact with German women.

The family business also benefited from taking over a biscuit factory in occupied Ukraine.

Three sons of the founder, Hermann Bahlsen, who were members of the board of directors, were also members of the Nazi Party and even financially supported the SS.

Verena Bahlsen had previously said that the company, which employed some forced labourers during World War II, “did nothing wrong” at the time. Pictured: Workers at the Bahlsen factory in Hanover in 1929

After the war, his participation was hardly questioned, not even by the Allies.

Mr. Berghoff said The times that Bahlsen threw off National Socialism “like an old garment and within a few weeks established excellent relations with the British Army, which, like the Wehrmacht, bought Bahlsen products in large quantities and frequented the factory.”

In a statement on the findings, the family said: ‘The results of the investigation show that our predecessors and protagonists of the time took advantage of the system during the Nazi era.

‘Their main motivation seemed to be to continue the enterprise under the Nazi regime, with dire consequences.

‘There was harm to people, in particular to more than 800 forced labourers between 1940 and 1945. That is inexcusable.

The company, which was owned by Verena Bahlsen’s great-grandfather in the late 19th century, employed around 200 forced labourers, mostly women, between 1943 and 1945. The company now has annual sales of more than €500m (£435m).

Three sons of founder Hermann Bahlsen (pictured) were members of the Nazi Party.

“The truth about these past events is painful and uncomfortable. We deeply regret the injustice committed against these people in Bahlsen. We also regret not having faced this harsh truth sooner.”

Verena Bahlsen, who has since retired from the company, first attracted controversy with her brazen claim to be a capitalist who “wants to make money and buy yachts with my dividends.”

When critics reminded him that his company profited from forced labor, Bahlsen, who stands to inherit a quarter of the family business, hit back.

“That was before my time and we paid the forced labourers as much as the Germans and treated them well,” he told German newspaper Bild, adding that the company had nothing to feel guilty about.

Werner Bahlsen has four children. His sons Johannes and Andreas Bahlsen remain members of the company’s board of directors.

The family has now pledged to use the historians’ findings to help work towards a better future and as a mission to prevent a repeat of Nazi crimes by promoting a “culture of remembrance”.

Verena Bahlsen, the great-granddaughter of the company’s founder, has apologised after sparking outrage by claiming her company treated forced labourers “well” during World War II.

Werner M Bahlsen is pictured here in 2016. His company’s annual sales are currently around £450m.

However, it appears to have failed to provide further financial compensation to victims of forced labour and their descendants.

A spokesman told The Times that Bahlsen donated 1.5 million German marks to the German government’s official forced labour compensation fund in the early 2000s.

Bahlsen’s annual sales are currently around £450m.

Germany has paid a total of 4.4 billion euros to more than 1.66 million people in almost 100 countries in compensation for forced labour and concluded the payments in 2007.

According to the Documentation Centre on Nazi Forced Labour, based in south-east Berlin, 26 million people, including prisoners of war, concentration camp inmates, Jews, Roma and Sinti, worked against their will for the Nazi regime.