Table of Contents

The baseball world lost one of its integral legends this Tuesday with the death of Willie Mays. For some, the sport lost its greatest player of all time.

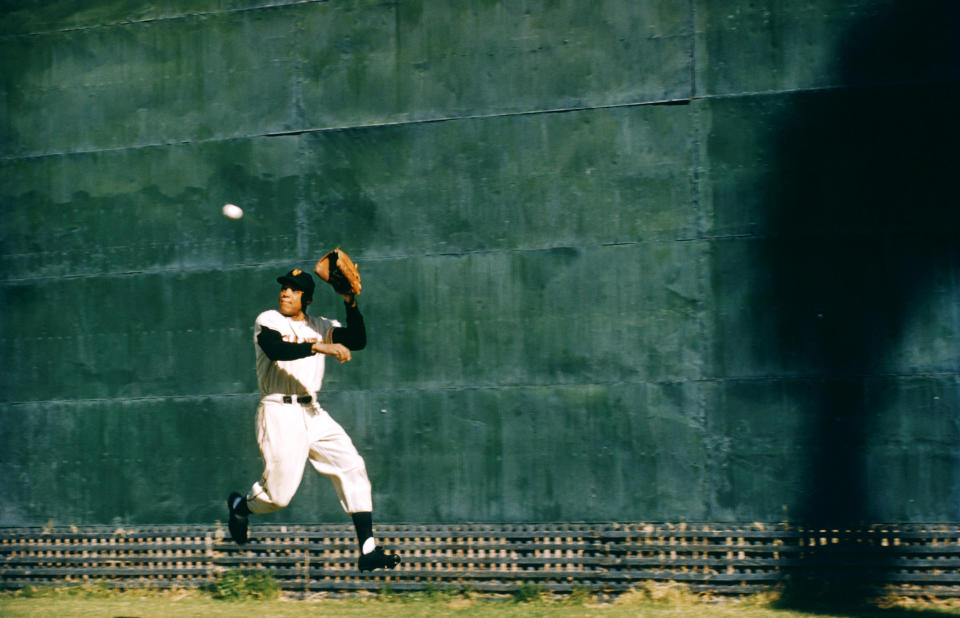

There is no shortage of ways to praise Mays’ 23-year major league career, from objective numbers to subjective anecdotes. He was the best offensive player in the history of his center field position, and was responsible for his defensive highlight. He dominated, he entertained, he lived in the memory of every witness of his playing career.

Visits: 3,293. Home runs: 660. All-Star selections: 24. Gold Gloves: 12. MVP Awards: 2 (with the argument that he deserved a few more). Home run titles: 4. Stolen base titles: 4. A World Series title, a Rookie of the Year award, a batting title, a four-homer game and even the inaugural Roberto Clemente Award for sportsmanship. It’s hard to think of a more complete resume than that.

But somehow Mays doesn’t come up as often as others in the conversation about baseball’s GOAT. For a century, the default answer was Babe Ruth. Then Barry Bonds interrupted the conversation for a while, and still does if you’re willing to ignore certain bad practices.

We remedy that.

Is Willie Mays the GOAT of the MLB?

It’s absolutely true that there has never been a better baseball player than Mays, especially considering some of the complications surrounding how Wins Above Replacement is used to lead the debate.

To start, let’s look at the Baseball Reference Leaderboard for All-Time WAR:

1. Babe Ruth, 182.6

2. Walter Johnson, 166.9

3. Cy Young, 163.6

4. Barry Bonds, 162.8

5. Willie Mays, 156.2

Notice some things about the guys in front of Mays?

We don’t need to dwell on this too much (you probably already know how much the following statement means to you), but it needs to be said: Willie Mays is the all-time leader in WAR among MLB players who competed in an Integrated League and never used steroids.

Would Ruth have been as dominant as Mays if he had been born 25 years later and faced the wave of black talent that came to MLB after Jackie Robinson? It’s impossible to say. But it’s not hard to argue that the era in which Mays shined for the Giants was when the league’s level of raw talent was at its highest, when every young man in America grew up wanting to be a baseball player and was encouraged to do so. provided the opportunity.

If that’s enough to convince you of Mays, great, but it’s also very possible to shore it up by accepting the premise that Ruth and others had no advantage because the WAR we use now is not the same as the WAR. used back then, even though it is treated the same way in the record books.

WAR changed how defense calculates after Willie Mays played

It’s relatively easy to calculate offensive WAR over the many decades of MLB history. Almost everything on the plate can be reduced to a few numbers that have survived the transition from literal record books to the online ledgers used today. Mays hit a home run on May 18, 1957, and we have a good idea of the effect it had on the game and how impressive it was, given the pitcher, the park, and the era.

Calculating defensive WAR is not so simple, as there is no concrete record of how many incredible catches a player made in his career.

That matters quite a bit when you realize that Baseball Reference pegs Mays’ career impact on the field as 18.2 wins above replacement. That number ranks 69th in all-time defensive WAR rankings, which is good but, well, it doesn’t quite align with Mays’ defensive reputation. Kevin Kiermaier is a very good defender, but it’s hard to imagine anyone would say he should be more than 10 spots ahead of Mays.

For outfields, modern defensive evaluation basically consists of a human or computer watching a game and recording how much a player had to run to make (or not make) a catch. Unfortunately, the system Baseball Reference uses for defensive WAR, Baseball Info Solutions’ Defensive Runs Saved, dates back only to the 2003 season.

For seasons prior to 2003, Baseball Reference uses something called Total Zone Rating, which does not include any type of player tracking. Here’s what B-Ref says it does instead:

Total Zone Rating (TZR) is a non-observational fielding system that is based in various ways depending on the level of data available, from basic fielding and pitching statistics to play-by-play, including types of batted balls and hit locations. . For each season all available data is used.

When play-by-play is available, TZR will use information such as ground balls fielded by infielders and outfielders to estimate hits allowed by infielders. It uses baserunner advancement and departure information to determine outfielder arm ratings, infielders’ double play acumen, and catchers’ arm ratings.

TZR is an impressive feat of statistical engineering, but its limitations for our purposes are obvious. It also becomes even more limited for seasons prior to 1953 (Mays debuted in 1951) due to the lack of play-by-play data.

The point is: The tool used to assess where Mays stands historically relative to his peers has some flaws. Normally, that’s not a big deal as long as you realize that WAR has a lot of variability (his critics will never hesitate to point out when the metric favors a player who seems to fall short compared to another in other numbers), but here, it’s a problem.

But is it enough to make up for the 26.4 WAR gap between Mays and Ruth, whose defensive evaluation is complicated for the same reasons? Again, it’s impossible to say, but it’s definitely worth considering.

Mays is remembered as perhaps the greatest defensive center fielder of all time, leading the position in Gold Gloves with 12, and WAR measures him as a pretty good defender. If you don’t think Mays’ defense was better than anything the numbers back then can capture, you’ve clearly never talked to a person who saw Mays play in person.

Willie Mays was the greatest hitter and outfielder combination of all time

There are a few ways to argue against Mays’ supremacy, such as the team’s lack of success, given that it only won one World Series ring (a contaminated one at that). The counterargument to that: trade Mays and Mickey Mantle, and see how well the New York Yankees did in the 1950s and 1960s. The rings are a very silly way to argue about an MLB GOAT, for that matter. so we will not stop at them.

Instead, let’s think about Mays with a wide lens. For two decades, he was one of the league’s most productive and consistent players at the plate, retiring with a 155 OPS+ (meaning his OPS was 55% better than the league average when accounting for the park). and the era). At the same time, he was baseball’s premier defensive machine; It’s just unfortunate that his career predates the time when highlight reels became commonplace.

If you care about how high a player’s ceiling was, Mays posted six seasons above the elite all-time mark of 10 WAR. If you care about how high a player’s floor was, Mays’ worst OPS+ between 1954 and 1966 was 146. He hit .296/.369/.557 with a league-leading 40 steals that year. If you care about a player’s character, he looks at all the memories of the people who knew him.

When it comes to discovering the GOAT of baseball, there really is no angle you can take that doesn’t end with Mays on the list, and that’s why so many people will present him as the greatest of all time. His personal preferences may vary, but Mays’s career does not.