In less than three weeks, millions of American families will sit around the table to say what they are grateful for and feast on hearty meals with store-bought turkey as the centerpiece.

However, a smaller portion of the country insists on hunting wild turkeys for the Thanksgiving holiday.

Those who venture into the woods each year with shotguns say it’s more special and more environmentally friendly than buying a farm-raised turkey.

Kristie Swenstad of Minnesota first joined her father on a hunt when she was 12 years old.

“I was excited because I was doing what my dad did,” she said. The New York Times. “I was going to help fill the freezer.”

Two hunters walk along a dirt road, one of them with a dead turkey on his back

Pictured: A hunter shows off the wild turkey he successfully shot down.

Swenstad, now 36, owns a tailor shop in Alexandria, a small lake town about 130 miles northwest of Minneapolis.

All these years later, he has kept the tradition of hunting alive and hopes more people will try it one day so they can appreciate what it really means to put food on the table.

Some people have fallen so in love with turkey hunting that they have traveled across the country to experience the challenges that different environments present, whether it be the wide open plains of Texas or the swamps and forests of Florida.

Billy Barnett, who directs Turkey Hunting USAhas harvested one turkey from all 49 states where they are native (Alaska is the only state without turkeys).

Doing this is known as the US Super Slam, and only 17 people completed the challenge and recorded it. the Wild Turkey Federation.

Barnett also went into the turkey hunting business.

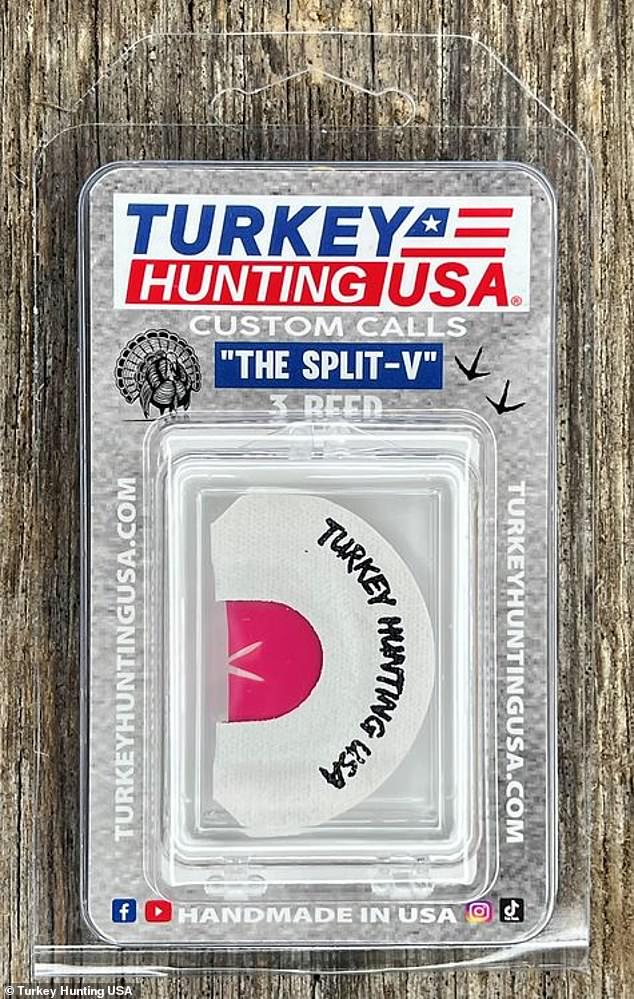

His company sells t-shirts, hats and different types of calls, which are devices used to bring turkeys closer to the hunter’s location.

Hunters make mouth calls, the cheapest of these, priced at just $11.99, to imitate the clucking and swallowing noises birds make.

Many hunters also use hen decoys to attract male turkeys, called bucks or gobblers.

Billy Barnett, pictured, has hunted turkeys in 49 states except Alaska, where the birds are native.

Barnett sells hunter calls, like this mouth call that is supposed to imitate the clucking noise that turkeys make.

Many hunters also use hen decoys, as shown in the photo, to attract male turkeys, called bucks or gobblers.

For those open to this hobby, there are two important caveats to consider and chief among them is where you are in the country.

If you live in Minnesota like Swenstad, the state isn’t even close to the best place to hunt turkeys.

Texas, Missouri and Pennsylvania have larger populations of wild turkeys and long hunting seasons to take advantage.

In Minnesota, turkeys were eradicated in the late 19th century due to unregulated hunting and loss of forest habitats.

After the last native turkey was sighted in 1880, there were several efforts to reintroduce it to the state beginning in the 1920s.

In 1971, the state Department of Natural Resources moved 29 turkeys from eastern Missouri to southeastern Minnesota.

Now Minnesota has about 70,000 turkeys, much more than zero, but a paltry number compared to The more than 500,000 inhabitants of Texas.

Of the 60,000 Minnesotans who have fall and spring hunting licenses, only a quarter of them, on average, bring home a turkey.

The other caveat is that even if you hunt a turkey successfully, it will not have as much meat as a farm-raised turkey would have.

They are much leaner, mainly because they have to exist in the wild and are not intentionally fattened by commercial farmers.

Swenstad is irritated by people who criticize hunting but have no problem buying meat at the supermarket for precisely that reason.

She argued that the turkeys she and her family kill are not forcibly driven through feedlots, which are designed to fatten the animals as quickly as possible. He also said most hunters are dedicated to preserving the habitats they traverse.

Wild turkey behaviors vary with the seasons. In the fall, there are fewer turkeys and they tend to congregate in quiet groups. The mating season is in spring, so many hunters prefer to go out at that time.

On the left is a classic supermarket turkey. On the left is a prepared wild turkey, which visibly has less meat.

“I like the fact that I know where my food comes from and I worked hard to have it on my table instead of just going to the store, where you don’t know where it comes from or what’s in it,” Swenstad. saying. “These turkeys are as close to pure as you can get.”

Because of this, turkeys have become part of Minnesota culture.

Look no further than Governor Tim Walz, who has talked about his experiences hunting turkeys.

After he was chosen as Kamala Harris’ running mate, his spicy turkey tater-tot recipe became the talk of food lovers online.

Wild turkey behaviors vary with the seasons. In the fall, there are fewer turkeys outside and they tend to congregate in quiet groups.

The mating season is in spring, so many hunters prefer to go out at that time. There are many male turkeys jumping and shouting to find a female.

“It’s so entertaining, like watching guys in a bar trying to impress women,” Brita Edgerton, a friend of Swenstad, told The Times. “They start coming in with their big tails and plumage, showing off.”

In the Swenstad household, turkey hunting has become a growing tradition over the years.

A hunter disguises himself with a wooden structure and uses a friction call to attract turkeys

A hunter takes aim at a group of several wild turkeys in front of him

Swenstad’s mother, Lynette, 58, usually stayed home cooking while everyone else hunted. But on Mother’s Day 2010, he finally decided to join a turkey hunt.

Now he loves it as much as the rest of his family.

“I like to sit in the quiet of the forest,” he said.

She might even be the most pragmatic hunter of all, as one day she shot a wild turkey she happened to see in her yard while standing in the yard.

Swenstad’s fiancé, Taylor Hayes, has also gone on the hunt. She didn’t grow up in a hunting family, but she got used to it after falling in love with Swenstad.

“He’s slowly getting into this because it’s all we talk about,” said Kyle, Swenstad’s brother.

Among them all, the calm, reflective act of being in nature is the most attractive part of hunting.

“I just like being here in God’s country,” Swenstad said. “It gives you this inner peace that you can’t find anywhere else.”