<!–

<!–

<!– <!–

<!–

<!–

<!–

Spanning six decades and following children from different social backgrounds, it is the documentary that has transcended generations.

And now the Up series has been named the most influential program of the past 50 years in a poll of members of the Broadcasting Press Guild.

First broadcast in 1964 on ITV, the program followed 14 seven-year-old children from the ‘fringes’ of society to represent Britain’s diverse socio-economic backgrounds, directed by Paul Almond.

Seven years later, Michael Apted, who had been a researcher on the first episode, took over and directed all subsequent episodes, including the latest in 2019 – two years before his death in 2021.

The series was filmed every seven years from 1964-2019 and tried to illuminate how a child’s upbringing can affect the rest of their life. Some of the participants dropped out over the years, while others have died.

The Up series has been voted the most influential program of the last 50 years in a poll of members of the Broadcasting Press Guild

First broadcast in 1964 on ITV, Up (pictured) followed 14 seven-year-old children from the ‘extremes’ of society to represent Britain’s diverse socio-economic backgrounds, directed by Paul Almond

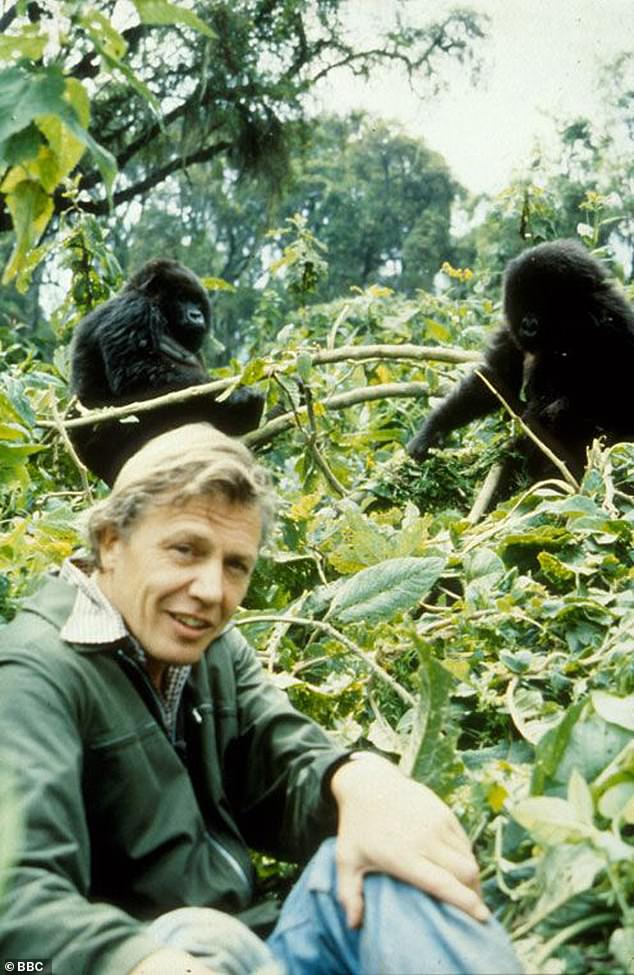

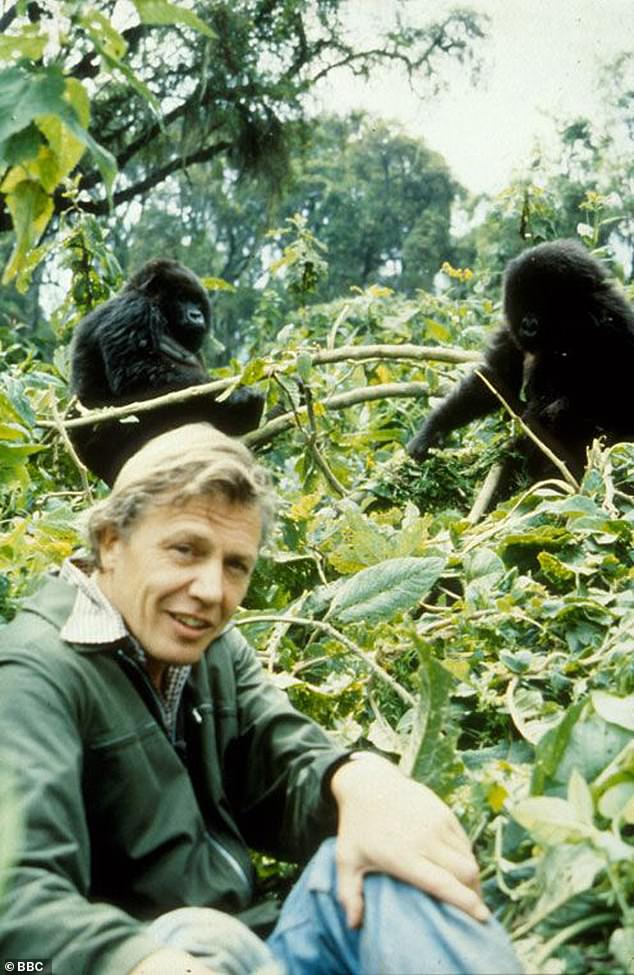

Second on the list of shows that ‘changed broadcasting, influenced how we look at the world and made us laugh or think in a new way’ is Sir David Attenborough’s BBC nature show Life On Earth, which first ran in 1979

In third is ITV’s 1973 series The World At War documenting the Second World War, followed by Ricky Gervais’ award-winning mockumentary The Office

The critically acclaimed program was inspired by Aristotle’s saying: ‘Give me the child until it is seven and I will give you the husband.’

The poll of the 50 most defining programs of the past 50 years includes documentaries, dramas, comedies and reality shows – with 31 of the entries broadcast on the BBC.

Second on the list of shows that ‘changed broadcasting, influenced how we look at the world and made us laugh or think in a new way’ is Sir David Attenborough’s BBC nature show Life On Earth, which first ran in 1979 .

Then in third place is ITV’s 1973 series The World At War documenting the Second World War, followed by Ricky Gervais’ award-winning mockumentary The Office.

Big Brother, which first started in 2000 on Channel 4 as a first-of-its-kind reality show and social experiment, is fifth on the list.

BPG chairman Manori Ravindran said: ‘For our 50 years, members of the Broadcasting Press Guild have been the tastemakers of the UK television industry.

“As such, it felt fitting to celebrate this milestone birthday with a Top 50 list that reflects the shows we believe have created defining television moments or have been truly significant to the industry during that time.

The BBC’s Blackadder came in at number 15, with the broadcaster leading the BPG’s top 50 landmark programs from the last 50 years list with 31 shows, while ITV and Channel 4 each have nine

Some recent shows to appear on the list include Michaela Coel’s hard-hitting drama I May Destroy You, about a woman trying to come to terms with being raped, and Fleabag (pictured)

Fan favorite Only Fools and Horses came in at number 19 – behind comedies including The Royle Family and The Thick Of It

‘It was not an easy process – and we welcome healthy debate about our choices – but we believe this list encapsulates the richness of the creative sector and its incomparable contribution to our culture and society.’

The BBC leads the BPG’s top 50 landmark programs of the last 50 years with 31 shows, while ITV and Channel 4 each have nine, while Sky, Netflix and Disney+ also make an appearance.

Some recent shows to appear on the list include Michaela Coel’s hard-hitting drama I May Destroy You, about a woman trying to come to terms with being raped, and the BBC’s smash hit reality show The Traitors.