Jelena Dokic has revealed she feared for her life amid heartbreaking abuse from her father Damir during her professional sporting career.

The Australian tennis champion, 41, has documented the abuse she suffered for years at the hands of Damir in her revealing feature film Unbreakable: The Jelena Dokic Story.

She appeared on Nova’s Jase & Lauren to talk about the documentary and recalled her life-or-death terror when she was just 17 years old.

Jelena told how her father forced her to play for Yugoslavia at the 2001 Australian Open, trapping her between Damir’s wrath and widespread public criticism.

She admitted that she was afraid of being beaten by her father if she did not agree to change the country she played for and at one point feared for her life.

“When I had to go from playing from Australia to Yugoslavia to 24 hours of walking across Rod Laver Arena to play Lindsay Davenport, I was literally caught between two fires,” he told hosts Jason Hawkins and Lauren Phillips.

Jelena Dokic has revealed she feared for her life amid heartbreaking abuse from her father Damir during her professional sporting career.

“Here my father, if he hadn’t gone and said it at a press conference that was suddenly called, when I got back to the hotel room, who knows, I probably wouldn’t have survived that beating.”

“Or here I had the media, the sponsors (and) the public who were going to beat me up, like they did, so what do you do?

“So of course I did that and 24 hours later you walk out and you’re in the Rod Laver Arena, 15,000 people booing you and everyone writing that you’re a traitor.”

Jelena heartbreakingly said she would have suffered “100 years” of abuse from Damir if it meant she could have continued playing for Australia.

“This always moves me, nothing more,” she said through tears.

“I’ve said it recently, and people find it shocking, that I would endure 100 years of abuse so that he wouldn’t have taken that moment away from me with my people, with Australia.

“I came back a few years later, yes, they accepted me, but it was never the same until my book came out, and until now.”

Jelena confessed that it was not the only time she feared for her life and was once knocked unconscious by her father’s beating while talking about running away from his influence at age 19.

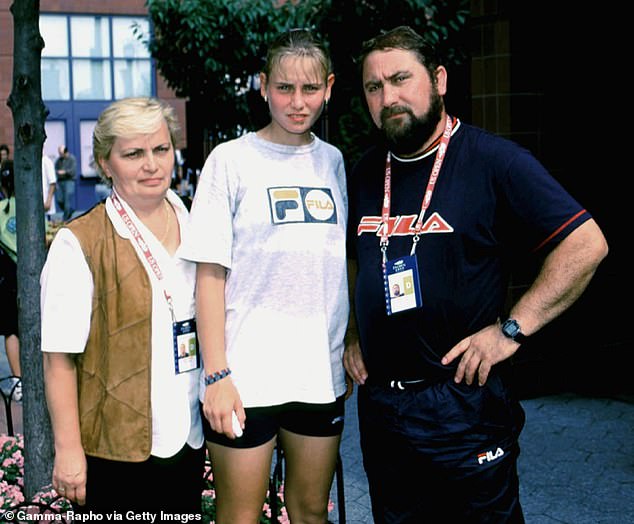

Speaking on Nova’s Jase & Lauren, Jelena recalled how she feared for her life when she was just 17 due to Damir’s abuse (pictured with her parents Damir and Ljiljana).

‘I had to leave at 19 because I didn’t know if I was going to survive the next beating,’ he explained.

‘There was one when I was 17 where I was knocked out, kicked and punched in the head so hard I was knocked unconscious.

‘This is what happens, next time you don’t know if you’re going to survive. I knew it, I knew he was getting more violent.

Jelena was born in Yugoslavia and her family moved to Australia when she was 11, where she began playing tennis.

She reached the quarter-finals of Wimbledon in 1999 and the semi-finals in 2000, followed by the quarter-finals of the 2002 French Open, but at the same time suffered terrible abuse from her father.

In her documentary, Jelena recalled how she felt pressured to win because Damir regularly beat her up.

“I knew if I lost the consequences would be catastrophic,” she said while watching footage of herself playing tennis.

‘One day after losing I knew what was going to happen… I was starting to feel really broken inside.

Jelena (pictured in 2011) told how her father forced her to play for Yugoslavia at the 2001 Australian Open and said she would now suffer “100 years” of abuse for not doing so.

‘There wasn’t an inch of skin that wasn’t bruised. I’m 17 years old and through his actions, (I) became the most hated person.’

Jelena also revealed that she does not “hate” her father for the abuse he suffered, although she cannot forgive him for his actions.

‘I don’t blame anyone. I have no resentment towards anyone. I definitely don’t hate anyone, I never would,” Jelena told the Daily Telegraph.

‘I’m not bitter about it. Even for my father, which people find surprising. But I don’t hate it. I don’t necessarily forgive him, but I don’t hate him.