Liam McArthur’s assisted dying for terminally ill adults bill splits Scotland down the middle. New figures show public responses are split almost 50-50.

The bill would make it legal for “health care professionals” to assist in the voluntary suicide of “a terminally ill adult who meets certain eligibility criteria.”

This is a topic that inspires strong opinions, based on personal experiences and nourished by deeply rooted religious and philosophical convictions.

The debate must be conducted in that spirit, but we must take sides and do so firmly. I am firmly against it.

There is no such thing as a perfect death, and no system for administering death can be perfect. This is as true for euthanasia as it is for capital punishment.

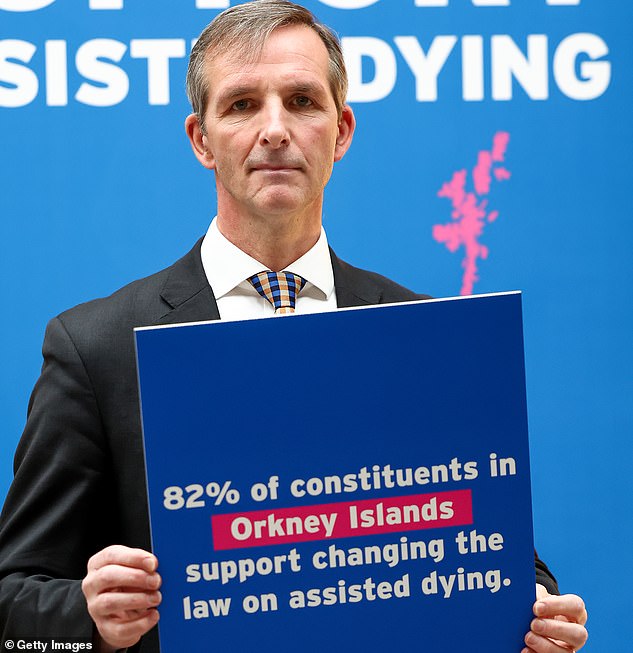

Liberal Democrat MP Liam McArthur is the driving force behind a bill at Holyrood proposing assisted dying for the terminally ill.

When the State gets involved in the business of ending life, it brings with it all the defects inherent to large bureaucracies.

Whatever its qualities, the NHS is a bureaucracy prone to mismanagement, systemic errors and a culture of cover-up.

But there can be no margin for error with euthanasia, just as there can be no margin for error with execution.

If we look at other countries when they adopt policies such as euthanasia, it is fair to observe their results.

Canada legalized medical assistance in dying (MAID) in 2016 and it was also initially limited to the terminally ill.

The courts then said it should be made available to patients with serious illnesses where death was not “reasonably foreseeable”.

The House of Commons complied and amended the law in 2021. The law has been amended again and from 2027 patients whose “only underlying medical condition” is a “mental illness” will be eligible for MDA.

During MAID’s first year, 1,018 Canadians were voluntarily euthanized, but by 2022 that number had skyrocketed to 13,241 — a 1,200 per cent increase in six years.

Doctors involved in MAID are now responsible for four per cent of all deaths in Canada, a figure that rises to nearly seven per cent in the province of Quebec.

The most frequently cited “nature of suffering” in AMM requests is “loss of ability to participate in meaningful life activities,” but “patient-perceived burden on family, friends, or caregivers” was cited in 35 percent of cases.

A 2023 study published in the journal Palliative Support Care “identified problems with the practice of MDA” and found increasing accounts of people choosing to end their lives “due to suffering associated with lack of access to medical, social and disability support.”

The researchers concluded that Canada’s euthanasia regime “lacks the safeguards, data collection and oversight necessary to protect Canadians from premature death.” If this can happen in an advanced and enlightened Canada, it can happen here.

None of this is meant to diminish the suffering of people who are terminally ill, bedridden and spending their final days, weeks or even months in agony.

Surely they have the right to end their pain and decide the terms on which their life will end?

Putting it in those terms, I understand and even sympathize with the arguments in favor of euthanasia.

Not just because it’s an emotional issue, but because it’s a human issue. Whenever we hear that someone has been diagnosed with stage four cancer or motor neurone disease or something similarly catastrophic, we try not to imagine ourselves or our loved ones in the same situation, but we can’t help it. We were there, but for the grace of God.

However, this debate is not about who is more compassionate or empathetic, but about the practical feasibility and moral acceptability of the State, through its nationalised health service, deciding who can and cannot take their own life and helping them to carry out their suicide.

And what we call “the State” is really us, the accumulation of our electoral and other preferences, the official articulation of who we are and the kind of country we want to be. The State does what it does in our name.

So, although it may seem that euthanasia is a personal matter, in reality it is something that affects us all.

It will be our parliament that tells our NHS that in our country doctors can choose not to fulfil their duty of care and instead help to kill.

The issue of assisted dying has sparked heated debate in Scotland

That Scotland is a place where one moment a doctor may have to administer a drug to save someone’s life and the next moment give someone a drug that will end their life.

That both actions are clinically and morally equal and legitimate.

They are not. Ending a human life, even at the request of the patient, is not medical care. It is killing. It may be done with the best of intentions, by doctors with an alphabet of letters after their names, to patients whose prognosis is terrifyingly certain, but it is still killing.

We already know this. That is why the law allows exceptions so that women can access abortion drugs or, more rarely nowadays, medical procedures that interrupt a pregnancy.

Doing so outside the circumstances established by law is a crime. Since the 1960s, society has been abandoning everything that smacks of prejudice and has moved towards a culture of autonomy in which we are all individuals with the right to make decisions independently of long-established moral or social restrictions.

On the whole, this has been a positive thing, but even in a liberal society there are certain things we should be prevented from doing, things that are fundamental to civilization, such as artificially altering the course of life and death.

If you ask “what if” questions about a proposal like this, you’ll likely be accused of the “slippery slope fallacy.”

But the slippery slope is not always a logical fallacy. It is often a simple observation of how politics works and evolves. There are several questions that can be asked about this bill.

What possible safeguards could be put in place to ensure that euthanasia assistance is granted only to those who wish to end their suffering, as opposed to those who are considered a burden on their family?

In other countries, euthanasia is a practice most often resorted to by older people, a demographic disproportionately affected by chronic loneliness and embarrassed at the thought of inconveniencing their children or other family members for an extended period of time.

The explanatory notes say that “no one, including registered doctors and other health professionals, will be required to participate in the proceedings if they have a conscientious objection to doing so”.

But if euthanasia becomes a service provided by the NHS, how long will an exemption of conscience be sustainable?

What happens when patients seeking to end their lives in remote and rural areas of Scotland begin to report difficulties in accessing lethal drugs?

This could be a real possibility in areas where there is a lower density of physicians and a higher percentage of religiosity and/or social conservatism. It seems likely that there would be a lot of pressure on conscientious objectors to participate in what would now be considered “health care.”

What will happen when, a little further down the road, the euthanasia lobby declares that the safeguards built into McArthur’s bill are “traumatising” and “humiliating” for terminally ill patients and demands that the process be “demedicalised”, making it primarily a matter of patient choice and reducing the role of doctors to that of a signature on a prescription?

I suspect we all know what would happen: Holyrood would abandon the safeguards and congratulate itself on its courage and progressiveness.

I respect those who have a different view on this issue. I believe they are good people who have good intentions and want the terminally ill to be treated with compassion, but I strongly disagree with the idea that killing can be a form of compassion.

Compassion would be to invest appropriately in palliative care to ensure that those who cannot recover can leave this life when their time comes with the greatest comfort and least pain possible. Life is precious and those who leave it should be treated as such.