<!–

<!–

<!– <!–

<!–

<!–

<!–

Millions of people across North America witnessed the incredible spectacle of a total solar eclipse on Wednesday, but excited Australians will have to wait another four years.

Australians across the country will be able to watch a total solar eclipse, the rare phenomenon that occurs when the moon passes directly in front of the sun, blocking it and casting a shadow on the Earth, known as “the path of totality.” ‘.

The next one will occur on July 22, 2028 and will last about five minutes as it travels across the country.

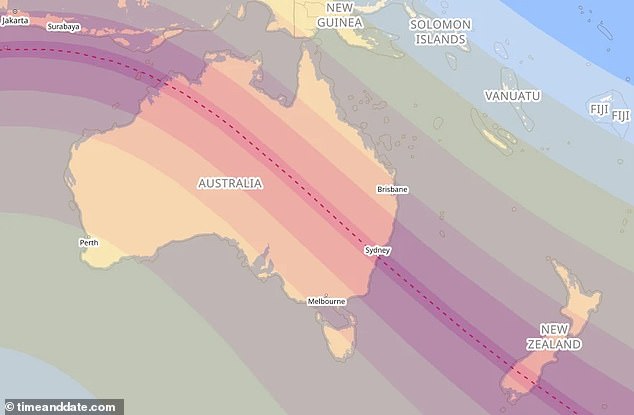

It has the longest path of totality, crossing the Kimberley in Western Australia, through the Northern Territory, south-west Queensland and Sydney on the east coast.

And avid stargazers are already getting excited.

A map showing the predicted path of the next eclipse has been circulating on social media, and many excited Australians are planning to take time off work for the celestial event.

A map showing the predicted path of the next eclipse has been circulating on social media, and excited Australians are planning to take time off work for the celestial event.

“Hey Siri, set a reminder for July 22, 2028,” one person commented on a Reddit thread.

“For those who can’t afford Sydney, consider going to Wyndham or Halls Creek,” wrote another.

“Maybe take a week off work and head west through Charleville… I think it would be nice to be in the middle of nowhere,” a third person agreed.

Australia will experience four total solar eclipses between 2024 and 2038.

On 25 November 2030 it will be visible across South Australia, north-west New South Wales and southern Queensland.

After that, on July 13, 2037, people in southern WA, southern NT, western Qld, Brisbane and the Gold Coast will be able to witness the eclipse.

And on December 26, 2038, it will be visible in central WA, SA and along the border of New South Wales and Victoria.

More than 30 million Americans came out to watch eclipse mania spread across the United States.

The next total solar eclipse will occur on July 22, 2028 and will last about five minutes.

Meanwhile, others tuned into NASA’s live broadcast.

On Monday, April 8, Americans were dazzled when part of the country was plunged into darkness as the moon passed between the Earth and the sun.

Crowds gathered from all over to watch the eclipse.

“It’s a great feeling to see the lights go out so quickly,” one person said.

“We were all in disbelief at this incredible moment in nature,” wrote another on X (formerly Twitter).

“The most amazing natural phenomenon on Earth, a total solar eclipse, swept through North America,” a third person agreed.