From lung cancer to heart disease and chronic bronchitis, it’s fair to say that the effects of cigarette smoking are well documented.

But a new study warns that this risky habit can even leave traces in bones for centuries after death.

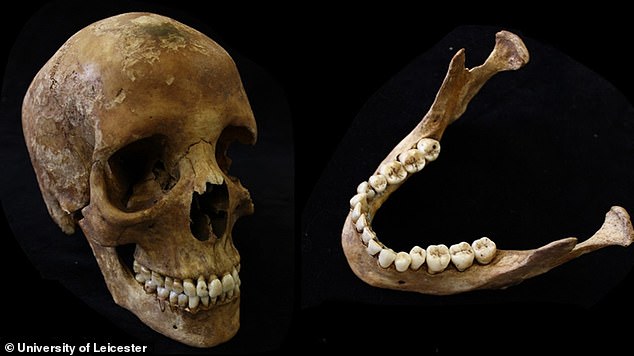

Researchers from the University of Leicester studied human remains buried in England between 1150 and 1855 AD

This timeline effectively intercuts the arrival of tobacco in Western Europe in the 16th century, an act commonly credited to Sir Walter Raleigh in 1586.

They discovered that smoking not only stains and dents teeth, but also leaves small chemical molecules on the teeth, potentially staying there forever.

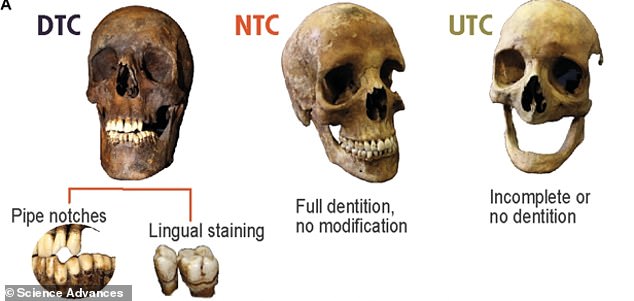

Scientists can tell if a deceased person smoked because of stains or marks on their teeth. For example, dents known as “pipe notches” would have been formed by a tobacco pipe, while “lingual staining” are black or brown marks on the part of the tooth surface that faces the tongue.

Experts examined 323 sets of skeletons discovered in two graves in England, and it was determined that some of them had smoked tobacco.

In the study, experts set out to discover more about these molecules and the effect they could have on human health today.

“Our research shows that there are significant differences in the molecular characteristics contained in the bones of past tobacco users and non-users,” said lead author Dr. Sarah Inskip, a bioarchaeologist.

“This potentially shows that we can see the impact that tobacco use has on the structure of our skeletons.”

Generally, scientists can tell quite easily whether an individual who died hundreds of years ago smoked because of stains or marks on their teeth.

For example, round dents known as “pipe notches” are gradually formed by the mouthpiece of a tobacco pipe.

Many centuries ago, tobacco pipes were made of clay and were therefore harder than today’s cigarettes, although today’s plastic vaporizers could cause such dents.

Meanwhile, “tongue stains” (black or brown marks on the part of the tooth surface that faces the tongue) are caused by smoke circulating and exhaled through the mouth.

However, sometimes a skeleton’s teeth do not survive or become detached from the rest of the body and are lost, making determining whether or not the person smoked more difficult, although not impossible.

The scientists established a method that looked for molecular traces of tobacco smoke in cortical bone, the dense tissue that forms the outer layer of bones and provides strength to bones.

The researchers studied bones from detected tobacco users (DTC) and undetected tobacco users (NTC). Many archaeological individuals have poorly preserved dental remains or lose teeth before death, categorizing them as indeterminate tobacco users (UTC).

A common date given for the arrival of tobacco in England is July 27, 1586, when Sir Walter Raleigh is said to have brought it to England from Virginia. Pictured is a portrait of Sir Walter Raleigh smoking (circa 16th century)

They examined 323 sets of skeletons discovered in two graves in England, and it was determined that some of them had smoked tobacco.

The total included 177 adult individuals from the St James’s Garden cemetery in Euston, London, dating from the 18th and 19th centuries.

The remaining 146 people were taken from the graveyard of a country church in Barton-upon-Humber, Lincolnshire.

The remains at Barton-upon-Humber included those who lived before the introduction of tobacco to Europe (1150-1500 AD) and those who lived after (1500-1855 AD).

By analyzing human skeletal remains from before and after the introduction of tobacco in Western Europe, the researchers were able to “clearly” identify bone changes.

The team identified 45 “discriminatory molecular characteristics” that differed between tobacco smokers and non-smokers.

What’s more, the team was able to identify whether the previously “undetermined” skeletons were smokers or not, identifying molecular similarities between them and known smokers.

“Tobacco consumption leaves a metabolic record in human bones that is sufficiently characteristic to identify its consumption in individuals whose tobacco consumption is unknown,” states the team in their article, published in Scientific advances.

Sometimes a skeleton’s teeth do not survive or become detached from the rest of the body and are lost, making a simple judgment about whether that person smoked or not impossible.

From lung cancer to heart disease and chronic bronchitis, it’s fair to say the lethal effects of cigarette smoking are well documented (file photo)

Overall, the study shows that tobacco consumption leaves a metabolic record in human cortical bone even hundreds of years after death.

This may be important in understanding why tobacco use is a risk factor for some musculoskeletal and dental disorders.

“This innovative research shows that archaeometabolomics has a lot to offer in terms of understanding past phenotypes, such as smoking,” they say.

“(This) can help us better understand health conditions in the past and their relationship to current trends.”

Looking ahead, the team wants to continue to better understand how tobacco affected the health of past populations since its popularization around the world.

Tobacco was introduced to Western Europe from America in the 16th century and has been present in England since at least the 1560s.

Sailors returning from Atlantic voyages captained by English naval commander Sir John Hawkins are believed to have brought it home after a voyage to Florida in 1565.

‘The Allegory of the Smoker’s Transience’ by Hendrick van Someren, painted around 1615 to 1625, depicts an old man smoking a clay pipe.

However, a more common date for tobacco’s arrival in England is July 27, 1586, when Sir Walter Raleigh is said to have brought it to England from Virginia.

Smoking tobacco was said to have enormous and varied medicinal properties, and its use became common in the 17th century.

This despite the fact that James I of England and James VI of Scotland condemned the use of tobacco in 1604 for its poisonous effects on the body.

James wrote that smoking was a “habit repugnant to the sight, odious to the smell, injurious to the brain, dangerous to the lungs, and, from the black and stinking smoke, closely resembling the horrible Stygian (very dark) smoke from the well.” . that has no bottom.’