It is believed that millions of species still exist in Earth’s oceans, which cover 70 percent of the planet.

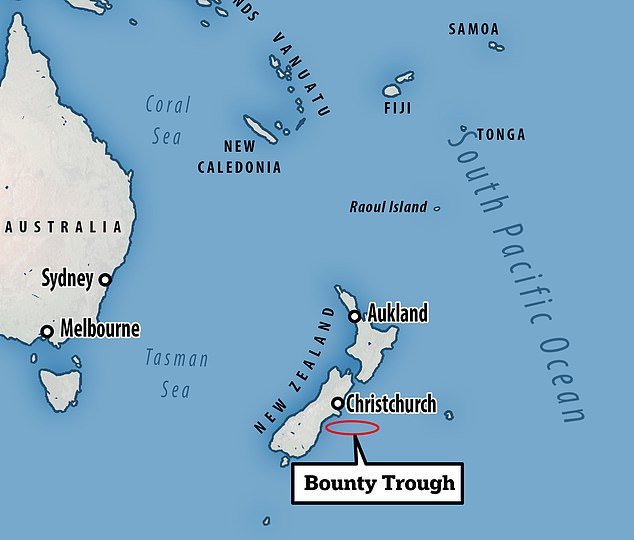

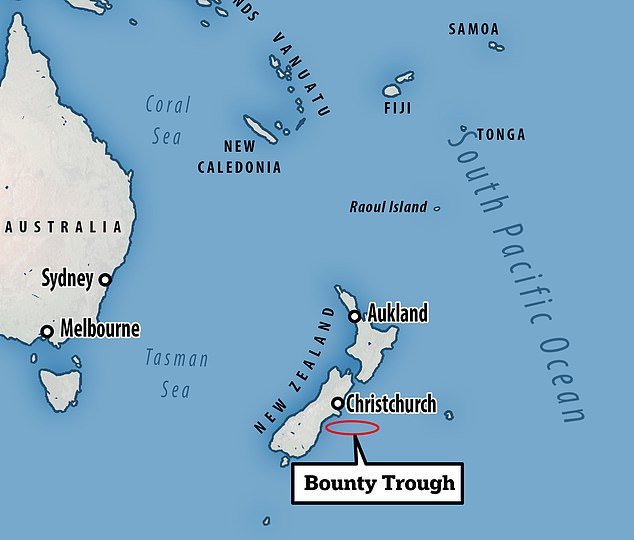

Now researchers have announced they have discovered another 100 after an expedition at the Bounty Trough, off the east coast of New Zealand’s South Island.

From a research vessel, the team dropped mesh nets to more than 15,000 feet to catch creatures lurking in the dark depths.

The new species identified there include dozens of molluscs, three fish, a shrimp, an octopus and a new genus of coral.

There is also a find – which looks like a shriveled gray cauliflower – that ‘astounds’ the marine biologists.

New species identified so far include dozens of molluscs, three fish, a prawn, an octopus and a new genus of coral – but one find (pictured) baffles experts

The new species was revealed by New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA).

Voyage co-leader and NIWA marine biologist Sadie Mills said the expedition has shown the Bounty Trough is thriving with life.

“We’ve gone to many different habitats and discovered a whole range of new species, from fish to snails, to corals and sea cucumbers – really interesting species that will be new to science,” she said.

The find, which is perplexing the experts, is likely a new type of octocoral – a deep-sea organism known to have polyps with eight tentacles.

The expedition team initially thought it might be a starfish, a sea anemone, or another deep-sea animal called a zoanthid, but so far it has turned out to be neither.

“We have a lot of experts here looking, who are very excited,” said Dr. Michela Mitchell, a taxonomist at the Queensland Museum.

‘We now think that it may be a new species of octocoral, but also a new genus.

“Even more exciting, it could be a whole new group outside of octocoral.

The find, which is puzzling the experts, is likely a new type of octocoral – a deep-sea organism known to have polyps with eight tentacles

In the picture, a possible new species of shrimp has been found. The expedition has shown that the Bounty Trough is thriving with life despite its dark depths

A deep sea squid. A global team of researchers is working to confirm the findings at taxonomic workshops in Wellington, New Zealand

Marine scientists collected nearly 1,800 samples from as deep as 15,748 feet (4,800 meters) underwater along the Bounty Trough

Marine biologists are sorting through the discoveries aboard the research vessel off the coast of New Zealand

‘If so, it is a significant discovery for the deep sea and gives us a much clearer picture of the planet’s unique biodiversity.’

Another creature may be a new species of carnivorous chiton – a type of mollusc that can be identified by their distinctive armored shells.

There is also what is believed to be an eel wagtail – the bizarre ray-finned fish that looks like an eel.

British marine biologist Professor Alex Rogers, who co-led the expedition, said he has been impressed by the sheer biodiversity of life they have discovered.

“It looks like we have a large haul of new, undiscovered species,” he said.

“When all our specimens have been examined, we will be north of 100 new species.

“But what’s really surprised me here is that this includes animals like fish – we think we’ve got three new species of fish.”

The three-week voyage on NIWA’s research vessel Tangaroa collected almost 1,800 samples from as deep as 4,800 meters underwater along the Bounty Trough.

Over the next three weeks, the team of researchers – which includes experts from the UK and Australia – will sort and describe the samples collected.

Pictured, what is believed to be an eel wagtail – the bizarre ray-finned fish that looks like an eel

The team of scientists from NIWA and Te Papa in New Zealand collaborated with experts from the UK and Australia to collect almost 1,800 samples

This creature may be a new species of carnivorous chiton – a type of mollusk that can be identified by their distinctive armored shells

New species of coral (pictured) are among the discoveries. Experts have been amazed by the sheer biodiversity of life they have discovered

The three-week voyage on NIWA’s research vessel Tangaroa collected nearly 1,800 samples from as deep as 4,800 meters underwater along the Bounty Trough

Specimens are to be held at the NIWA Invertebrate Collection and the National Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, both in Wellington.

According to Andrew Stewart, curator of fish at Te Papa, there are likely many more species ‘still waiting to be discovered’ on future expeditions.

“While our results are significant, we know we’ve barely scratched the surface of the Bounty Trough,” he said.

Knowledge gained from the expedition will be included in future editions of the New Zealand Marine Biota NIWA Biodiversity Memoir.