With war expanding in the Middle East, the Russian invasion of Ukraine still in full swing, and China threatening to invade Taiwan, the world has arguably not been closer to the brink of nuclear war in generations.

Researchers have begun to sound the alarm once again about the risks of a nuclear winter: Imagine an Earth hidden from the sun by up to 165 million tons of soot and freezing 16 degrees Fahrenheit below the global average temperature.

all out Nuclear war could ruin crops around the world, reducing global calorie production by 90 percent, according to agricultural and atmospheric scientists.

But an international team of researchers has found a salty, tasty answer: vast seaweed farms, strung along the ocean’s surface with ropes and buoys, could help save up to 1.2 billion lives.

An all-out nuclear war could reduce global calorie production by 90 percent, but an international team of researchers has found a salty and tasty answer: vast algae farms strung along the ocean’s surface with ropes and buoys could help. to save up to 1.2 billion lives.

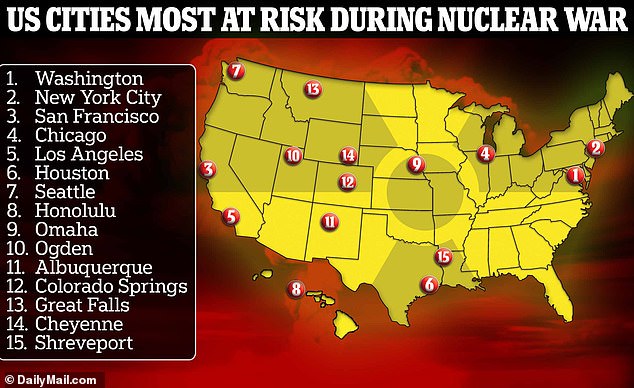

These 15 American cities are likely targets of a nuclear attack, based on population density, aerial distance to a strategic military installation, emergency preparedness and ease of evacuation, according to an analysis by independent financial experts at 24/7 Wall Street.

The team estimates that an average life-saving performance of up to Each year, 33.63 tons of dried seaweed could be grown on a modest surface of the ocean and with a reasonable budget.

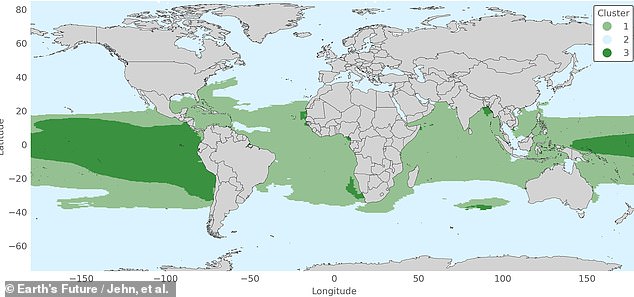

“If the most productive areas are used, around 416,000 square kilometers (160,619 square miles) of ocean are needed,” the study’s lead author, environmental scientist Dr. Florian Ulrich Jehn, told DailyMail.com, “which is approximately the size of Colombia.’

Dr. Jehn, data science lead for the Colorado-based Alliance to Feed the Earth in Disasters (TODOFED), collaborated with Louisiana State University’s Department of Ocean and Coastal Sciences, a German astrophysicist, and scientists from Texas and the Philippines on the project.

The economic cost of this intensive program to keep billions of people fed during a harsh nuclear winter, Dr. Jehn said, would be less than previous successful U.S. programs.

“In the article we compared the increase to aircraft production in the US during World War II,” Dr. Jehn said in an email interview.

“We estimate that the expansion would probably require fewer resources and therefore should be feasible,” he added, “but it is still a work in progress.”

One factor that Dr. Jehn said remains ambiguous, although his team is still crunching the numbers, was what The real price of seaweed could reach in such a scenario.

The study’s lead author, environmental scientist Dr Florian Ulrich Jehn, told DailyMail.com that around 416,000 square kilometers or 160,619 square miles of ocean “about the size of Colombia” would be needed for the project. Above, fishermen collect ‘maesaengi’ seaweed off South Korea

Dr. Cheryl Harrison, who directs Louisiana State’s Ocean Biophysical Modeling Laboratory, said vertical ocean convection has been well documented during winter months at high latitudes, but nuclear winter would move the cycle closer to the equator, which would help the cultivation of seaweed.

Their study, published this month in the journal The future of the Earthtook advantage of ocean climate models for the dramatic changes that will occur in the midst of a true nuclear winter.

“When the ocean surface cools, the water becomes denser, so it sinks, which drives vertical circulation,” says the study’s co-author. Dr. Cheryl Harrison told DailyMail.com.

The result would be convection-like agitation that would push nutrient-rich water from the depths of the ocean to the surface, effectively fertilizing the regions needed for this massive aquaculture program.

“This is formally called “penetrative convection,” Dr. Harrison explained, “and is the opposite of the convection that occurs on the stove when boiling pasta, where cold water sinks instead of warm water rising driving vertical circulation. “.

However, the researchers emphasized that people do not need to imagine a future of filling their plates with moist, salty sea plants at every meal. Only 15 percent of the food humans currently consume would be converted to seaweed. For the most part, it would be reoriented toward animal feed and biofuels.

Dr. Harrison, who heads Louisiana State University Ocean Biophysical Modeling LaboratoryHe said this process has been well documented during the winter months in high latitudes, but nuclear winter would bring the cycle closer to the equator.

“In nuclear winter, it stays cold for years, so it keeps going, churning up the deep water and nutrients there,” as he put it via email.

“Because it’s dark and cold, phytoplankton, the algae that make up the base of the ocean’s food web, don’t deplete these nutrients as quickly.”

According to Dr. Harrison, more human-friendly ocean vegetables, such as seaweed, “thrive well in these conditions, making them an excellent alternative food source.”

However, the researchers emphasized that people do not need to imagine a future of filling their plates with moist, salty sea plants at every meal.

Because the iodine found in seaweed can be toxic to humans in such high quantities, the algae’s contributions to the food web would likely be more indirect.

They estimate that seaweed farms would replace only 15 percent of the food currently consumed by humans, but would be mostly redirected toward the production of animal feed and biofuels.

Researchers believe that up to 50 percent of current biofuel production and 10 percent of livestock and other animal feed needs could be served by this Colombia-sized archipelago of algae farms.

The project also has less apocalyptic and worst-case uses, Dr. Harrison said. Living sciencenoting that it could also serve as humanitarian aid after the most likely disruptions in the global food supply chain.

Everything from a massive asteroid impact or a gigantic volcanic eruption to a regional crop failure or local drought could be offset by a similar algae farming program.

“Throughout history, large eruptions have caused famines both regionally and globally,” Dr Harrison said.

“In any case, we need a plan to feed ourselves in these sudden reduction in sunlight scenarios.”