A common plastic additive found in everything from pacifiers to metal food cans and even paper receipts has been linked to an increased risk of autism in children.

The new research, which followed the development of more than 600 babies, found that higher levels of bisphenol A (BPA) in a pregnant mother’s urine tripled the odds of a toddler developing autism symptoms by age two.

Worse yet, those same children were six times more likely to be diagnosed with autism at age 11, compared to those whose mothers had lower levels of BPA during pregnancy.

BPA, a chemical intended to toughen plastics and prevent metals from rusting, among other uses, has also been linked to increased risks of obesity, asthma, diabetes and heart disease over more than two decades of increasing scrutiny of the compound.

New research from Australia, which followed the development of more than 600 babies, found that elevated levels of bisphenol A (BPA) in a pregnant mother’s urine tripled the likelihood of a toddler developing autism symptoms by age two.

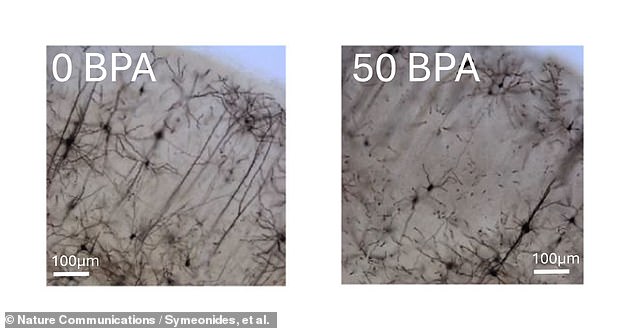

In addition to surveying more than 600 human children, who have been followed since 2010, the study also looked at laboratory mice to analyze the effect BPA has on brain development and autism. Photomicrographs of cortical neurons in laboratory mice (above) show the harmful impact of BPA.

It has also been called a “gender-bending” chemical due to its apparent role in stimulating hormonal and sexual disorders in humans, fish, and other species.

But the new study not only identified the apparent link, it also uncovered evidence to unravel the specific chemical reactions that contribute to cases of autism.

‘Our work is important because it demonstrates one of the biological mechanisms potentially involved,’ says the epidemiologist and public health physician Dr. Anne-Louise Ponsonbysaid in a statement about his team’s study.

“BPA may disrupt hormonally controlled fetal male brain development in several ways,” Dr. Ponsonby explained, “including silencing a key enzyme, aromatase, which controls neurohormones and is especially important in fetal male brain development.”

Aromatase, the new study noted, helps convert some male sex hormones in the brain, known as neuronal androgens, into neuronal estrogens.

These estrogens help all people, regardless of gender, to regulate inflammation in the brain, maintain the flexibility of the synapses that help the communication of neurons within the entire nervous system and also help in the control of cholesterol.

The brain is the organ in the human body that is richest in cholesterol: it uses approximately 20 percent of the body’s total reserves of these fatty molecules to perform its vital functions.

“We found that BPA suppresses the aromatase enzyme and is associated with anatomical, neurological and behavioral changes,” said study co-author and biochemist. Dr. Wah Chin Boon.

“This appears to be part of the autism puzzle,” Dr Ponsonby said.

The team’s research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature CommunicationsThey took two separate research approaches to arrive at these findings.

“BPA may disrupt hormonally controlled fetal male brain development in several ways,” explained public health physician Dr. Anne-Louise Ponsonby, “by silencing a key enzyme, aromatase, which controls neurohormones and is particularly important in fetal male brain development.”

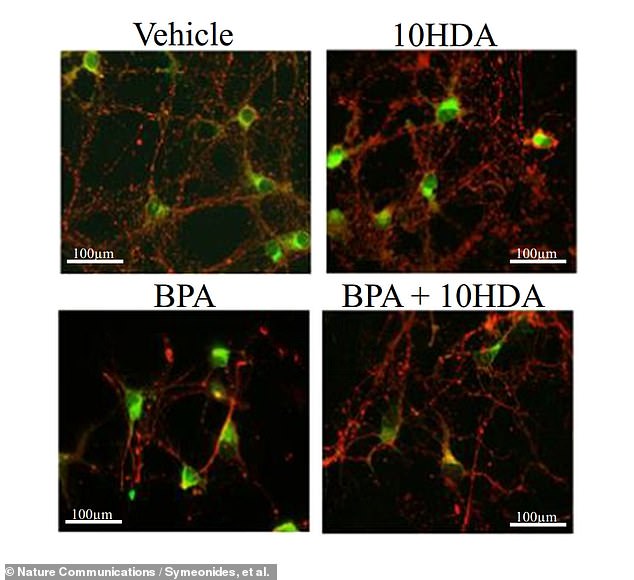

The team experimented with adding a type of fatty acid called 10-hydroxy-2-decenoic acid (10HDA), which they found could help mitigate the negative impact BPA has on the developing brain’s aromatase system. Above 10HDA, the impact of BPA on mouse neurons is reduced.

First, it took a deep dive into data collected since 2010 by two Australian universities that have been tracking a battery of health metrics for more than 1,000 participating children and their parents, known as Barwon Infant Study (BIS) Birth Cohort.

Within the BIS data, 676 infants were screened sufficiently for early autism symptoms for the team to draw statistical conclusions.

These assessments, drawn from the Child Behavior Checklist Autism Spectrum Problems (CBCL ASP) scale, were weighted to cancel out any genetic predisposition or other variables to isolate the role BPA plays during pregnancy.

The result of this weighted analysis was that toddlers with “low aromatase activity” were found to be 3.56 times more likely to show signs of autism at two years of age.

This continued as the children grew older, they observed: ‘CBCL ASP at age two years strongly predicted autism diagnosed at age four years and moderately so at age nine years.’

The connection to an autism diagnosis was true for 92 percent of four-year-olds and 70 percent of nine-year-olds, the study found.

But the team also conducted tests on laboratory mice in an effort to understand how BPA undermines this critical aromatase activity and what treatments can help combat it.

During those tests, the team experimented with adding a type of fatty acid called 10-hydroxy-2-decenoic acid (10HDA) which they found could help mitigate the negative impact BPA has on the developing brain’s aromatase system.

“When administered to animals that have been prenatally exposed to BPA,” Dr. Boon explained, “10-hydroxy-2-decenoic acid shows early indications of potential to activate opposing biological pathways.”

10HDA, an important fatty lipid ingredient found naturally in royal jelly from bees, competes within the brain with BPA, preventing the disruptive compound from binding to estrogen receptors.

In their mouse studies, adding 10HDA to BPA-exposed male mice improved their ability to socialize with other mice.

“Further studies are needed to see if this potential treatment could be applied to humans,” Dr. Boon said.