Scientists have reconstructed the face of an ancient Egyptian pharaoh who was brutally murdered 3,500 years ago, revealing how the king met his destiny.

Seqenenre-Tao-II, also known as ‘The Brave One’, was killed when he was captured in the middle of the night or on the battlefield at the age of 40 while attempting to liberate Egypt from the Hyksos people in 1555 BC

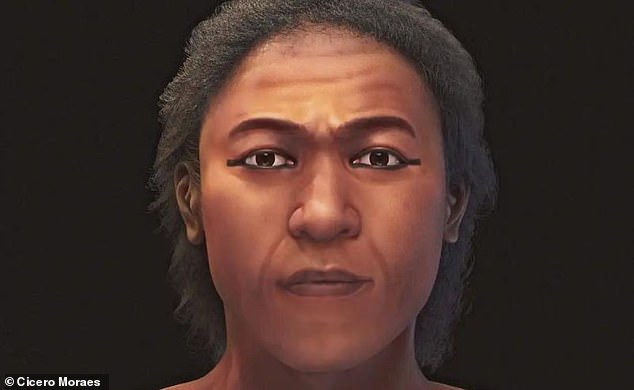

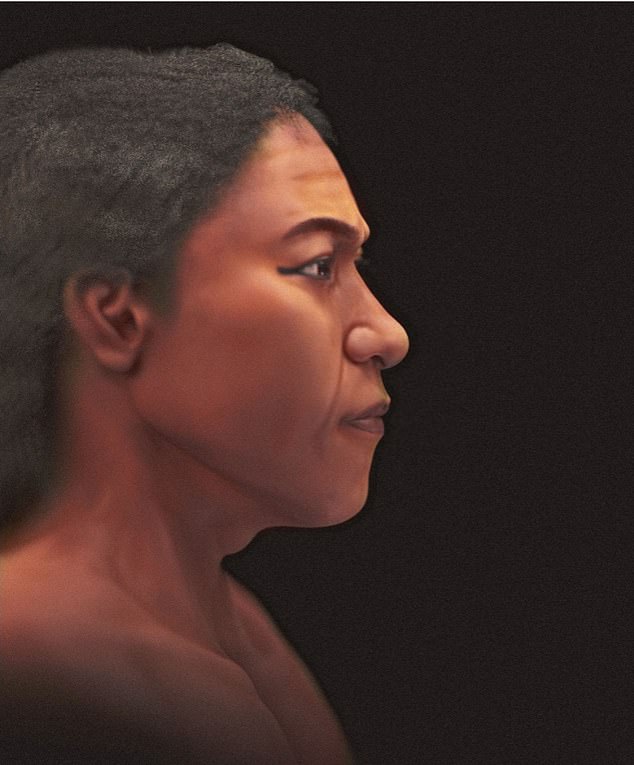

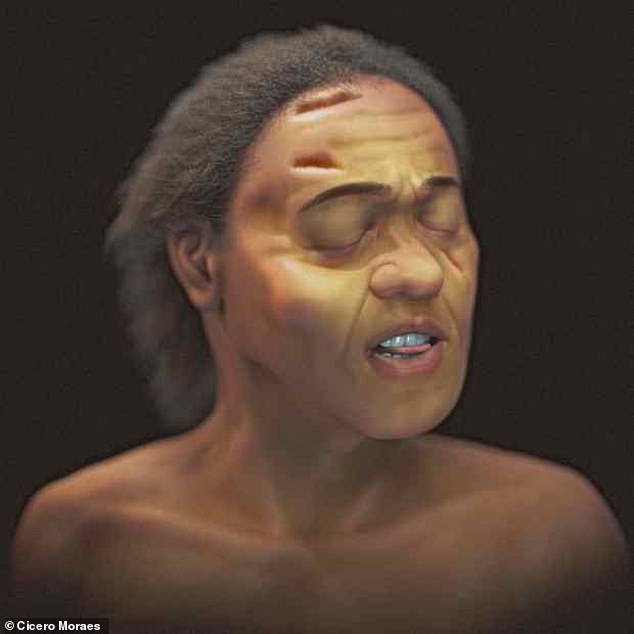

A team of archaeologists from Australia’s Flinders University reconstructed his face using CT scans and X-rays of the king’s shattered skull, showing the pharaoh with small eyes and lips and high cheekbones.

Facial reconstruction also revealed that a blow to the upper region of Toa’s brain likely caused his death.

Scientists have reconstructed the face of an ancient Egyptian pharaoh who was brutally murdered 3,500 years ago, revealing how the king met his destiny.

Seqenenre-Tao-II, also known as ‘the Brave’, was killed in his sleep or gunned down on the battlefield while attempting to liberate Egypt from the Hyksos people in 1555 BC

How the pharaoh died, whether captured or on the battlefield, has been a topic of debate since his remains were found in the 19th century.

But what is known is that there were several assailants who attacked Tao from different directions.

Tao’s face was reconstructed using his skull found by archaeologists in a tomb complex known as Deir el-Bahri, within the Theban necropolis, back in 1886.

They digitally scanned the remains, uploaded them to a computer and filled in the blanks with a skull from another individual that had previously been digitized.

The other skull was altered until it matched Tao’s, a process called anatomical deformation.

The team set to work drawing a digital profile of the king’s face and made the skin color similar to what was common among ancient Egyptians: ‘does not necessarily reflect the real color of the skin,” the study reads.

The shape of Toa’s eyes, eyelashes and eyebrows are also subjective elements, but researchers said they humanize the former king.

A team of archaeologists from Australia’s Flinders University reconstructed his face using CT and X-ray images of the king’s shattered skull, showing that the pharaoh was of Nubian descent, with small eyes and lips and high cheekbones.

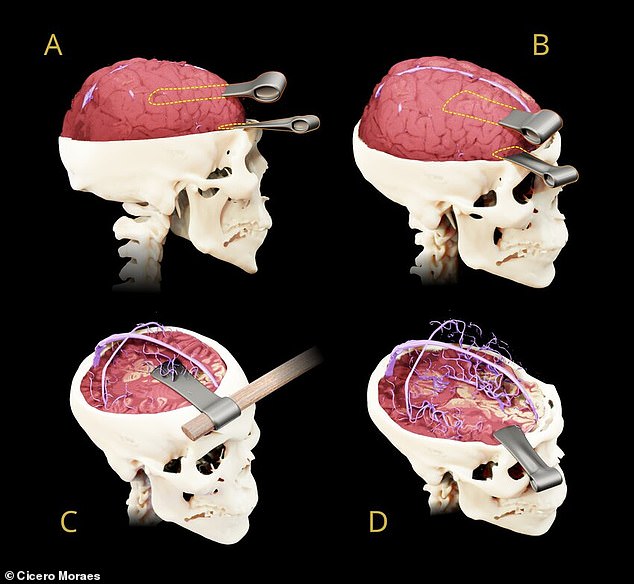

The team drew information from previous investigations to understand how the death unfolded, which showed that the first ax blow was to the right lower frontal area and left cheek.

Toa’s remains were first analyzed in 1886 by Egyptologists who first identified a wound just above his eyebrow bone and that his tongue had been bitten between his teeth.

The team also used thickness markers to match those of African ancestry and then added digital wounds to see exactly how the objects hurt the king.

Digital skulls with an exposed brain were then used to see which ax may have killed the king, revealing that the largest wound had penetrated his brain.

The weapon pierced the superior sagittal sinus, likely causing hemorrhage that caused Tao to breathe his last.

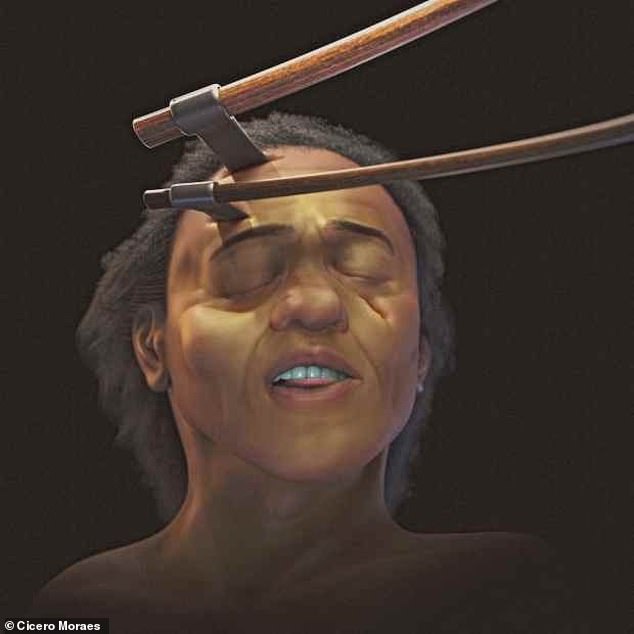

For the post-mortem images, the team left his lips slightly open and his tongue between his teeth due to some injuries and facial deformities that would have caused details when Tao was killed.

One of the weapons pierced the superior sagittal sinus, which likely caused the bleeding that caused Tao’s last breath (image C)

For the post-mortem images, the team left his lips slightly open and his tongue between his teeth due to some injuries and facial deformities that would have caused details when Tao was killed.

Gaston Maspero, a French Egyptologist, discovered the brave pharaoh among hundreds of coffins and mummies in 1886.

Maspero determined that Tao was slender, with a small, elongated head and fine, curly black hair – based on the hair left on the mummified body.

The pharaoh ruled the Theban region of southern Egypt from approximately 1560 to 1555 BC. C., during the seventeenth dynasty.

At the time, lower and middle Egypt was occupied by the Hyksos, a dynasty of Palestinian origin who ruled from the city of Avaris in the Nile delta.

Tao was the father of two pharaohs: Kamose, his immediate successor, and Ahmose I, who ruled after a regency by his mother.

Gaston Maspero, a French Egyptologist, discovered the brave pharaoh among hundreds of coffins and mummies. Maspero determined that Tao was tall, slender, with a small, elongated head, black, and fine, curly hair – based on the hair left on the mummified body.

Egyptologists James Harris and Kent Weeks, who conducted a forensic examination of Tao in the 1960s, said that “an unpleasant, oily odor filled the room the moment the box in which his body was displayed was opened.”

This smell was attributed to bodily fluids being accidentally left on the mummy at the time of burial.

During the embalming process, those performing the ritual pack the body with a mineral that dries it out.

But experts have suggested that Toa’s mummification was hastened because his body was left with fluids, but the reason is still unknown.