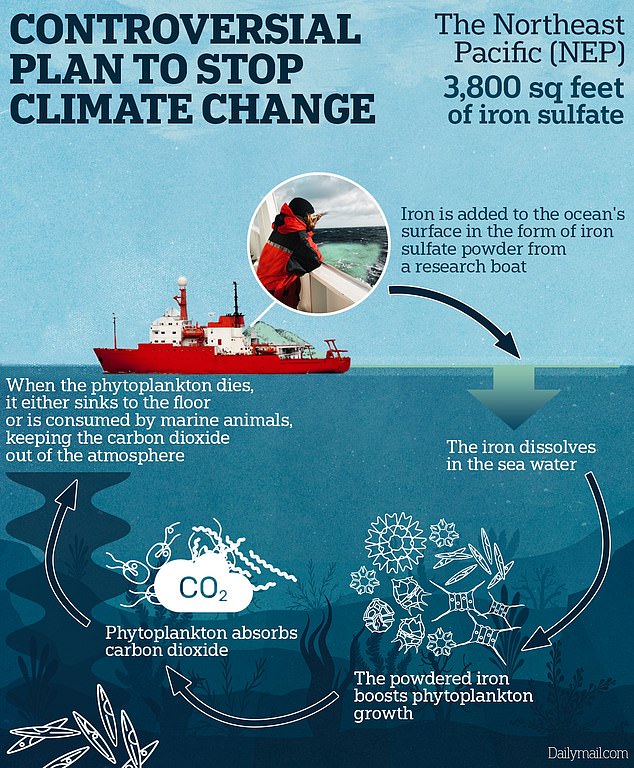

Scientists have proposed a controversial method to combat climate change: filling a giant swath of the Pacific Ocean with iron.

The technique, called ocean iron fertilization (OIF), pours a form of iron powder onto the sea surface to stimulate the growth of tiny marine plants called phytoplankton, which consume carbon dioxide and trap the gas in the ocean.

Computer models showed that by releasing up to two million tons of iron into the sea each year, the effort would remove nearly 50 billion tons of carbon dioxide by 2100.

Researchers plan to release the iron over 3,800 square miles in the northeast Pacific by 2026.

Iron can help phytoplankton thrive, which will absorb carbon dioxide from the ocean, preventing it from entering the Earth’s atmosphere.

A team of scientists from the nonprofit Exploring Ocean Iron Solutions (ExOIS) is exploring the possibility of spreading iron sulphate in areas where the nutrient is scarce.

This includes the northeastern Pacific Ocean, which extends from the west coast of North and South America to the east coast of Asia and up to the Arctic.

By distributing iron in these areas, scientists can stimulate phytoplankton growth, keeping carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere for years to come.

Removing CO2 from the ocean is critical, as it can help mitigate climate change by reducing the amount of greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere.

Every year, around 40 billion tons of carbon dioxide are released into the atmosphere, of which the ocean absorbs approximately 30 percent.

Researchers hope that by distributing iron sulfate in the ocean, they will help the world limit global warming to 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit.

However, critics have warned that iron could deplete nutrients from marine life, killing off part of the ocean’s food chain.

But the plan is still going ahead and the timeline is only two years away.

Scientists are now working on a way to convert iron into a powder that can be easily dissolved in water and dispersed in specific areas of the ocean.

As the iron dissolves, it acts as a stimulant for phytoplankton, helping them to grow rapidly, sometimes in a matter of days.

The nutrient boosts the tiny plant’s photosynthesis (the process of using sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and water into energy) by up to 30 times its normal output.

Scientists have reintroduced the idea of distributing iron in the sea to combat climate change

When phytoplankton die, the CO2 it absorbed will also sink to the bottom of the sea, preventing it from escaping into the atmosphere.

Dozens of experiments were conducted in the 1990s and 2000s, including an experiment in the northeast Pacific in 2006 that successfully caused phytoplankton to bloom.

Despite its success, some researchers have expressed concern that the OIF could negatively impact parts of the ocean ecosystem.

“Most likely (iron fertilization) affects something we don’t fully understand yet,” said deep-sea expert Lisa Levin, who was not involved in the ExOIS program. American scientist.

Scientists fear that the OIF could create “dead zones” that allow algae blooms to grow and consume all the oxygen in the water, killing all other living things.

Before researchers can begin their efforts, however, they need to raise $160 million to fund the program, but so far they have only received a $2 million grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

They also need to seek approval from the US Environmental Protection Agency to conduct trials after an international ban on commercial iron fertilisation of oceans was implemented in 2013.

The ban does not apply to OIF for research purposes, provided that they are carried out under strict control and do not harm the environment.