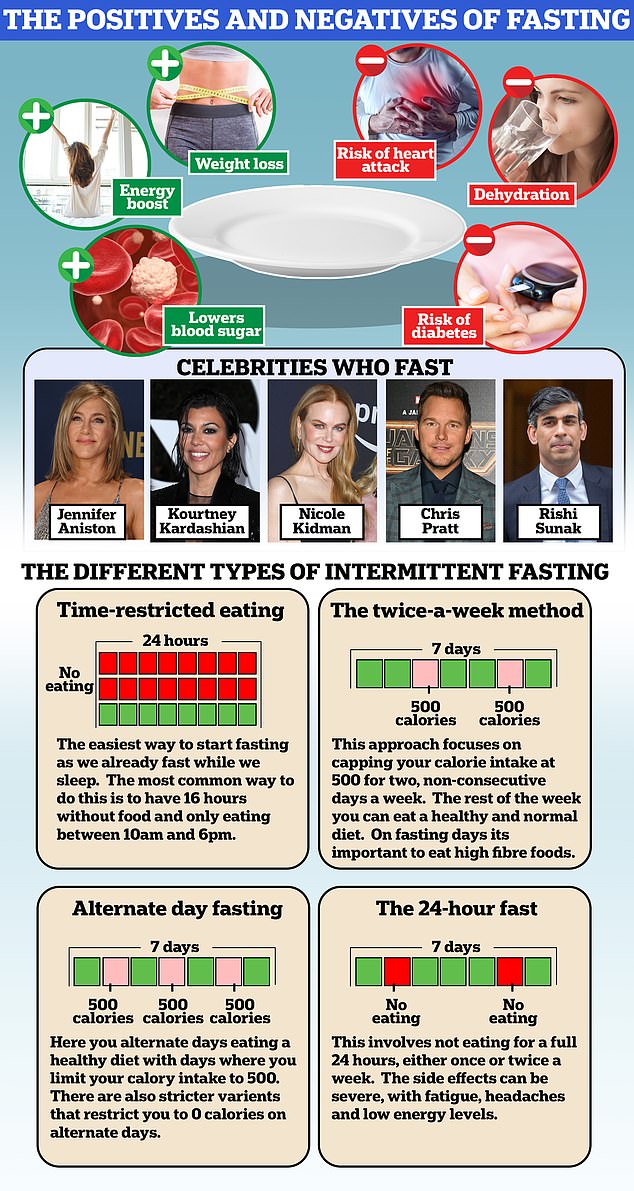

It’s a diet trend endorsed by everyone from Hollywood celebrities to Rishi Sunak, but intermittent fasting doesn’t work for everyone.

Now scientists say they’ve found a way to boost its effects: by focusing on what you eat, rather than when you eat.

Specifically, a group of American researchers discovered that the diet is only effective for losing weight and stabilizing blood sugar when people who follow it consume fewer calories than they need.

In other words, the amount of calories you consume matters more than the timing.

Obese people who maintained a 10-hour eating window, from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., eating most of their calories in the morning, lost 2.3 kg (5.1 lb) on average over 12 weeks.

Jennifer Aniston, Chris Pratt and Kourtney Kardashian are among the Hollywood celebrities who have embraced the trend since it rose to fame in the early 2010s. But despite numerous studies suggesting it works, experts remain divided over its effectiveness and potential long-term health impacts.

For comparison, volunteers who ate between 8 a.m. and midnight, consuming most of their calories in the evening, lost 2.6 kg (5.7 lbs).

Both groups of volunteers followed an expert-recommended diet that included a balance of fruits and vegetables, whole grains and no junk food, with little saturated fat.

Nisa Maruthur, co-author of the study and associate professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, said: “It makes us think that people who benefit from time-restricted eating (i.e. lose weight) are probably doing so because they are eating fewer calories because their time window is shorter, rather than because of anything else.”

Jennifer Anniston, Chris Pratt and Kourtney Kardashian are among the Hollywood celebrities who have embraced the fasting trend since it rose to fame in the early 2010s.

But despite numerous studies suggesting it works, experts remain divided over its effectiveness and potential long-term health impacts.

Some argue that fasting individuals often end up consuming a relatively large amount of food in one sitting, meaning they do not cut back on calories, a known way to combat obesity.

Even they warn that it can increase the risk of strokes, heart attacks or premature death.

The researchers analyzed data from 41 participants, aged 59 and with an average BMI of 36.

At the beginning of the study, researchers assessed participants’ activity history and level to estimate baseline caloric needs.

Participants received prepared meals with identical macronutrient and micronutrient compositions.

They ate the same amount of calories daily throughout the study.

During feeding windows, the trial did not limit beverages if they were calorie-free and caffeine-free.

Participants were also allowed to drink one cup of coffee, one diet soda and one alcoholic beverage per day. Outside of designated time periods, they were only allowed to drink water.

After 12 weeks, the scientists also found no real differences in fasting glucose, waist circumference, blood pressure or lipid levels.

Writing in the diary Annals of Internal MedicineThe researchers said: ‘Time-restricted eating did not reduce weight or improve glucose homeostasis relative to a habitual eating pattern.

‘This suggests that any effects of time-restricted feeding on weight in previous studies may be due to reductions in caloric intake.’