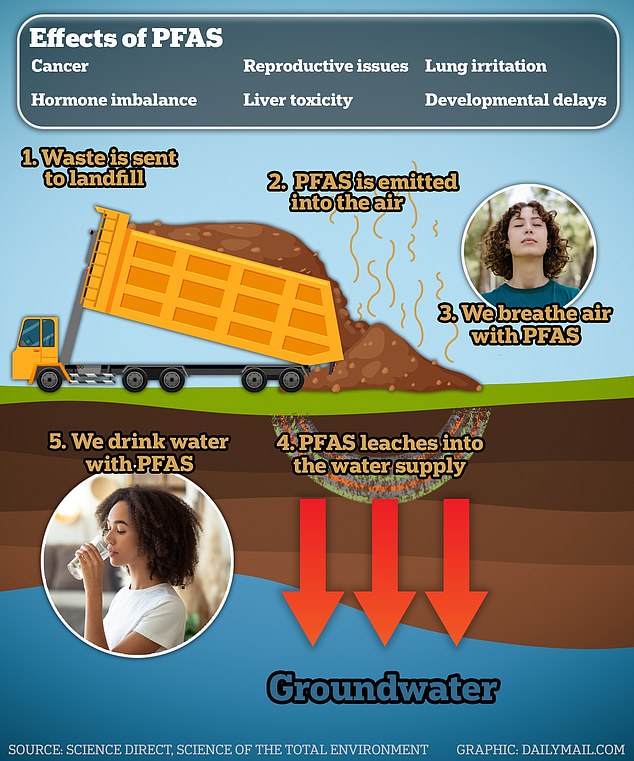

Landfills across the United States “belch” toxic gases into the air as waste decomposes, introducing a flood of permanently suspended chemicals into the atmosphere and poisoning the air we breathe.

Permanent chemicals, so called because they can survive in the environment and the human body for months or even years, are known to increase the risks of thyroid, kidney and testicular cancer, heart disease and liver damage.

The chemicals, also known as PFAS, are everywhere. They have permeated food and water supplies. They line food wrappers, nonstick cookware, and water-repellent clothing, form firefighting foam, and make certain clothing stain-resistant.

Researchers analyzed the air around three landfills in Florida that had been filled with PFAS-laden food, clothing, cosmetics and decomposing sewage sludge.

They found that 13 different types of permanent chemicals were circulating in the emitted gas, contaminating the surrounding air and potentially harming anyone who breathed it even from miles away.

Researchers at Yale University and the University of Florida already knew that water drains through waste materials in a landfill and leaches into groundwater and surface water. This is known as leachate.

Their goal was to understand how this seepage of PFAS-laden water compares to the composition and mobility of PFAS in toxic gases emitted from landfills. Once PFAS enter the air, they can spread widely, even across continents.

Researchers worked to determine which pathway (leachate or landfill gas) contributes most significantly to the release of PFAS from landfills.

They went to three different sites in Florida and installed air pumps to extract gas.

The bomb contained a cartridge filled with resin that traps compounds floating in the air. They then took those cartridges to the lab to isolate the compounds trapped in the resin.

The belched gas is composed primarily of methane and carbon dioxide, but these scientists also discovered that the gas was full of everlasting chemicals.

Most of the PFAS they found belonged to a class of compounds called fluorotelomeric alcohols. Like other PFAS compounds, fluorotelomer alcohols have a high fluorine content, allowing them to remain in the environment for months or years.

Fluorine concentration in landfill gas ranged from 32 to 76 percent of the total PFAS mass, compared to 24 to 68 percent in landfill leachate.

Even under conservative assumptions, the mass of PFAS coming out through the landfill gas was comparable to or greater than that of the leachate.

Researchers installed air pumps in landfills to collect PFAS-laden gas

According to the researchers: “These findings suggest that landfill gas, a less-analyzed byproduct, serves as an important pathway for PFAS mobility from landfills.”

Landfill leachate, the liquid that drains from landfills, is typically collected and treated to prevent further contamination of the environment. However, landfill gas, which includes methane and PFAS, is released into the atmosphere without treatment or control.

The study suggests that while pollution mitigation efforts generally focus on PFAS in the drinking water supply, the gas released from these mass disposal sites should be included in future plans to reduce exposure to the chemicals.

Some landfills flare these gases or capture them for energy, but researchers argue that these methods may not be effective at removing airborne pollutants.

PFAS pose a long list of health risks ranging from cancer to organ damage. The chemicals lodge in body tissues where they can survive without breaking down for more than seven years.

In 2023, doctors at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York analyzed blood samples from people with and without thyroid cancer and found that patients with the disease were 56 percent more likely to have levels of PFAS chemicals in their system. .

PFAS also cause inflammation in the body, leading to DNA damage in thyroid cells. This can result in genetic mutations that drive the creation of cancer cells.

Meanwhile, researchers from the University of California, San Francisco, the University of Southern California, and the University of Michigan showed that women with higher exposure to PFAS were twice as likely to report a prior melanoma diagnosis than women in the group with the least exposure to chemicals.

The study also found a link between PFAS and a prior diagnosis of uterine cancer, and women with higher exposure also had a marginal increase in the odds of having prior ovarian cancer.

And PFAS can wreak havoc on the body’s hormonal balance that governs fertility and reproduction.

American and Singapore researchers reported last year that women with several types of PFAS in their blood who were trying to conceive were up to 40 percent less likely to become pregnant and give birth to a live baby.

The results of the experiment were published in the journal. Environmental science and technology letters.