Scientists have discovered a secret Mayan city hidden in Mexico, which once featured an urban landscape of more than 6,500 structures.

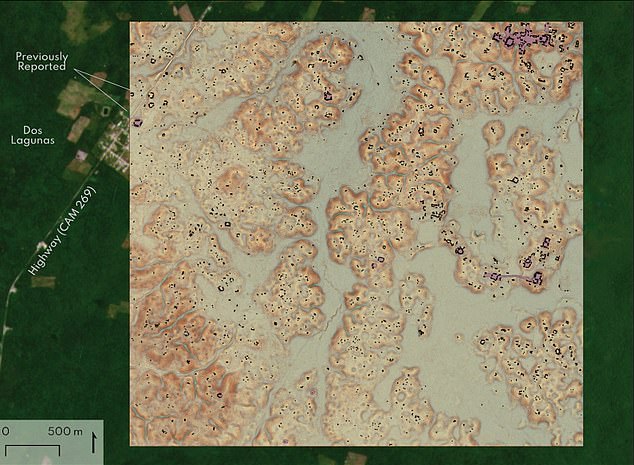

The team used lidar technology to create three-dimensional models across 50 miles of land in Campeche, allowing them to map areas not visible to the naked eye.

The method revealed a 21-square-mile metropolis with iconic stone pyramids, houses and other infrastructure that have been hidden for more than 3,000 years.

There are hundreds of documented Mayan sites, but the most recent find revealed that researchers are nowhere near finding all the major Mayan cities.

“Our analysis not only revealed a picture of a settlement-dense region, but also revealed great variability,” said study co-author Luke Auld-Thomas, a doctoral student at Tulane University.

‘We not only find rural areas and smaller settlements. “We also found a large city with pyramids right off the only road in the area, near a village where people have been actively farming among the ruins for years,” Auld-Thomas said.

The city, called Valerian, included a dam, a ball court, houses and terraces, as well as a curved amphitheater and pyramidal temples.

There are hundreds of documented Mayan sites, but the most recent find revealed that researchers are nowhere near finding all the major Mayan cities.

The team conducted an aerial LIDAR study, which It uses laser pulses to measure distances and create three-dimensional models of specific areas.

It has allowed scientists to scan large swathes of land from the comfort of a computer lab, discovering anomalies in the landscape that often turn out to be pyramids, family homes and other examples of Mayan infrastructure.

“Because lidar allows us to map large areas very quickly, and with really high precision and levels of detail, that made us react: ‘Oh wow, there are so many buildings that we didn’t know about, the population must have been huge,'” he said. Auld-Thomas.

“The counterargument was that LIDAR studies were still too tied to large, well-known sites, such as Tikal, and had therefore developed a distorted picture of the Mayan lowlands.

‘What if the rest of the Mayan area was much more rural and what we had mapped so far was the exception rather than the rule?’

The team discovered two Mayan city blocks, one of which included a distinct pseudopyramid that was identical to the one found at Río Bec, a pre-Columbian Mayan archaeological site located near the border with Guatemala on the Yucatán Peninsula.

The city, called Valeriana, was adjacent to a freshwater lagoon and encompassed two main areas of architecture including a dam, a ball court, houses and terraces.

Valeriana also contained a curved amphitheater, pyramidal temples and a reservoir that “has all the characteristics of a classic Mayan political capital,” according to the study.

The study was conducted near a highway and revealed a hidden city with more than 6,5000 structures.

The Mayan city was discovered near Campeche in Mexico and covers approximately 21 square miles.

“The discovery of Valeriana highlights the fact that there are still large gaps in our knowledge about the existence or absence of large sites within yet unmapped areas of the Maya Lowlands,” the researchers shared.

A third region of the city was identified as a “modest and sparse settlement, consisting of dispersed or loosely grouped residences without monumental architecture and with limited investment in water storage.”

Tulane professor and co-author Marcello Canuto said, “Lidar is teaching us that, like many other ancient civilizations, the lowland Maya built a diverse tapestry of cities and communities over their tropical landscape.”

He continued: ‘While some areas are filled with vast agricultural plots and dense populations, others have only small communities.

“However, we can now see the extent to which the ancient Maya changed their environment to support a complex and enduring society.”

Although hundreds of sites have been found, it is impossible to determine exactly how many Mayan cities remain to be studied.

However, lidar technology is helping researchers discover them much more quickly, particularly in southern regions of Mexico and Guatemala.

‘The government never found out; The scientific community never found out. “This really puts an exclamation point behind the statement that no, we haven’t found it all, and yes, there is much more to discover,” Auld-Thomas said.