Scientists trained an AI through the eyes of a baby in an effort to teach the technology how humanity develops, amid fears it could destroy us.

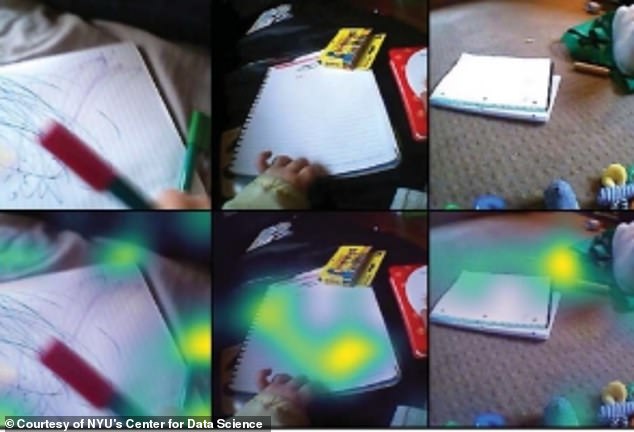

Researchers at New York University fitted a headcam recorder to Sam when he was just six months old and turning two years old.

The 250,000-word footage and corresponding images were fed into an artificial intelligence model, which learned to recognize different objects in a similar way to how Sam did.

The AI developed its knowledge in the same way the child did: by observing the environment, listening to people nearby, and connecting dots between what was seen and heard.

The experiment also determined the connection between visual and linguistic representation in a child’s development.

Researchers at New York University recorded a first-person perspective of a child’s appearance by placing a camera on six-month-old Sam (pictured) until he was about two years old.

The researchers set out to discover how humans link words to visual representation, such as associating the word “ball” with a round bouncing object rather than other features, objects or events.

The camera randomly captured Sam’s daily activities, such as meal times, reading books and the boy’s play, which amounted to about 60 hours of data.

‘By using AI models to study the real language learning problem that children face, we can address classic debates about what ingredients children need to learn words: whether they need language-specific biases, innate knowledge, or simply associative learning to get started. . ‘ said Brenden Lake, assistant professor in the Data Science Center and Department of Psychology at New York University and lead author of the paper.

The camera captured 61 hours of footage, equivalent to about one percent of Sam’s waking hours, and was used to train the CVCL model to link words to images. The AI was able to determine that she was seeing a cat

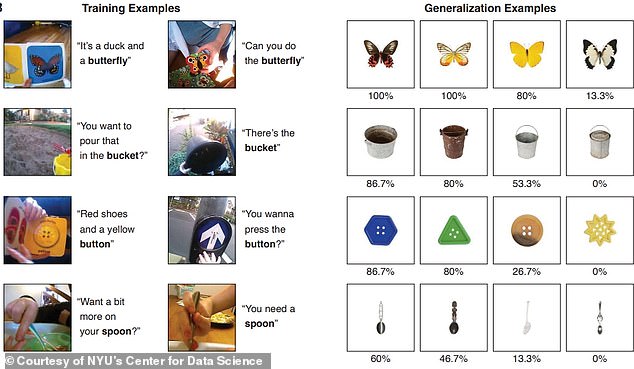

The CVCL model accurately linked images and text about 61.6 percent of the time. The photo shows the object that the AI was able to determine based on the images.

“It seems we can achieve more just by learning than is commonly thought.”

The researchers used a vision and text encoder to translate images and written language so that the AI model could interpret the images obtained through Sam’s headphones.

Although the images often did not directly link words and images, the Child’s View for Contrastive Learning (CVCL) model robot, composed of AI and the front camera, was able to recognize the meanings.

The model used a contrastive learning approach that accumulates information to predict which images and text go together.

The researchers presented several tests of 22 separate words and images that were present in the child’s video and found that the model was able to correctly match many of the words and their images.

Their findings showed that the AI model could generalize what it learned with an accuracy rate of 61.6 percent and was able to correctly identify unseen examples like “apple” and “dog” 35 percent of the time.

“We show, for the first time, that a neural network trained with this evolutionarily realistic data from a single child can learn to link words to their visual counterparts,” said Wai Keen Vong, a research scientist at the Center for Data Science and New York University. York. first author of the article.

“Our results demonstrate how recent algorithmic advances, combined with a child’s naturalistic experience, have the potential to reshape our understanding of early language and concept acquisition.”

The researchers found that there are still drawbacks to the AI model, and while the test showed promise in understanding how babies develop cognitive functions, it was limited by its inability to fully experience the baby’s life.

One example showed that CVCL had trouble learning the word “hand,” which is usually something a baby learns very early in life.

“Babies have their own hands and have a lot of experience with them,” Vong said. NatureHe adds, “That’s definitely a missing component in our model.”

The researchers plan to conduct additional research to replicate early language learning in young children around two years old.

Although the data wasn’t perfect, Lake said it “was totally unique” and presents “the best window we’ve ever had into what a single child has access to.”