Table of Contents

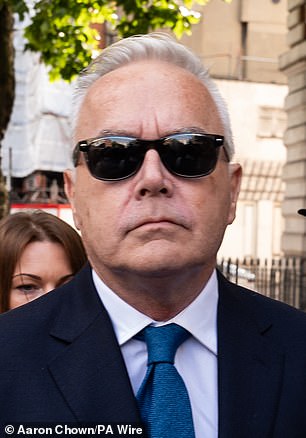

Fallen star: former BBC presenter Huw Edwards

The BBC should follow the example of British corporations and strip Huw Edwards of his salary.

Many TV licence holders will be wondering why the disgraced news presenter was awarded £200,000 following his arrest for child sex offences in November last year.

Director general Tim Davie has said the BBC will look at all options to recover some of the money, but that this will be “legally complicated”.

That sentence sounds like Davie has given up before he even starts, but he should try to get the money back with vigor.

Relieving errant chief executives of money they should never have received in the first place has become a welcome fact of life in the FTSE 100.

In the wake of the financial crisis, new rules – malus and clawback – were introduced to stop businessmen walking away with millions they didn’t deserve.

Clawback, as the name suggests, means clawing back incentives and bonuses that have already been delivered and cancelling those that have not yet been paid.

Malus is the opposite of a bonus: basically, a reduction or loss of a performance-linked reward.

One of the biggest losers of recent times from these arrangements is former BP boss Bernard Looney, who was found to have deliberately misled his board about personal relationships with colleagues. This cost him more than £32m.

Sebastien de Montessus, the former chief executive of Endeavour Mining, also paid a heavy price. His former employer said earlier this year that it wants to recover more than $29m (£23m) in salary and other compensation after firing him for alleged serious misconduct over “irregular payment”.

A dinner party indiscretion cost NatWest bank boss Alison Rose £7.6m in payments she would have received had she not spoken to a BBC editor about Nigel Farage’s bank account.

In the United States, financial punishment can be very painful indeed.

Just ask Steve Easterbrook, the British-born former chief executive of McDonald’s. He handed back $105m (£82m) worth of cash and shares after an investigation found he had secret affairs with staff.

Obviously the BBC is not the same.

In boardrooms, pay is made up of a relatively small cash element (though often in the seven figures), plus a range of much larger bonuses and incentive plans.

Some of them take several years to mature, so it is quite easy to dismiss those that have not yet borne fruit. Claiming money that has already been paid is much more difficult.

There are no stock incentives available for BBC staff, so in Edwards’ case it would mean chasing him for money or trying to shame him into giving it back, as Culture Secretary Lisa Nandy has suggested.

His pension is almost bloated. Fred Goodwin, the man who brought down RBS, kept his huge retirement pot, even though he nearly brought down the UK financial system. He receives around £545,000 a year.

To use Davie’s phrase, it is “legally complicated” for companies to pursue wealthy, litigious and well-connected CEOs for penalties and compensation. These ex-bosses are billionaires and can unleash legal attack dogs on their former employers.

But FTSE 100 companies are becoming more assertive in clawing back undeserved rewards from disgraced bigwigs.

This is changing the culture in British corporate life for the better.

The BBC should follow suit.

DIY INVESTMENT PLATFORMS

AJ Bell

AJ Bell

Easy investment and ready-to-use portfolios

Hargreaves Lansdown

Hargreaves Lansdown

Free investment ideas and fund trading

interactive investor

interactive investor

Flat rate investing from £4.99 per month

Saxo

Saxo

Get £200 back in trading commissions

Trade 212

Trade 212

Free treatment and no commissions per account

Affiliate links: If you purchase a product This is Money may earn a commission. These offers are chosen by our editorial team as we believe they are worth highlighting. This does not affect our editorial independence.