More than 200 branded food products aimed at babies and young children in the UK do not meet the World Health Organisation’s nutrition and marketing standards, according to an international study.

Two-thirds of products aimed at children aged six months to three years from Heinz, Nestlé, Danone, Hipp, Hero and Hain Celestial contained excess sugar, salt or calories.

The rest were found to be marketed deceptively, including nutrient-poor snacks, purees, cereals and ready meals labeled as “healthy”.

Of 1,297 products assessed internationally, including 218 sold in UK supermarkets, none were considered suitable for promoting consumption to children.

Of 1,297 products assessed internationally, including 218 sold in UK supermarkets, none were considered suitable for promoting consumption to children. In the photo, one of the products that did not meet WHO nutrition and marketing standards: Heinz Peach Multigrain Porridge for Babies 7 Months and Up from Kraft Heinz.

The brands studied hold more than 53 percent of the market share. The United Kingdom has the second largest number of such products after Italy. In the photo, one of the products that did not meet WHO nutrition and marketing standards: Ellas Kitchen Summer Pudding for babies 7 months and older from Hain Celestial.

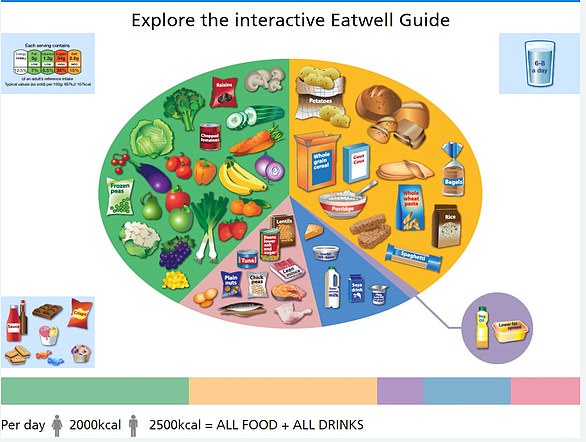

Your browser does not support iframes.

Greg Garrett of the Access to Nutrition Initiative (ATNI), a global nonprofit that conducted the research, said new regulations are needed to control the nutrient composition and marketing of baby and children’s foods. little ones.

“There is a worrying trend in the nutritional quality of commercial foods for babies and young children in several countries,” he said. ‘We must ensure that the wellbeing of young children is no longer undermined.

“To do this, we need the industry to take appropriate action, corporate shareholders to invest responsibly, and policymakers to improve regulations.”

The brands studied hold more than 53 percent of the market share.

The United Kingdom has the second largest number of such products after Italy.

Results varied between companies: Kraft Heinz had the highest percentage of products meeting nutrient composition requirements, about 42 percent, followed by Hero at 39 percent and Danone at 38 percent.

Researchers said 88 per cent of Hain Celestial products sold in the UK should have a “high sugar” warning label on the front of the package.

The same was true for 60 percent of Hero, 50 percent of Hipp, 46 percent of Kraft Heinz and seven percent of Danone products.

The study said new regulations should ban the use of added sugars and sweeteners, limit sugar and sodium content, and ban deceptive marketing and labeling practices.

Governments should introduce mandatory warning labels on products with high levels of sugar to help parents choose healthier foods for babies and young children, he added.

ATNI calls for greater support for parents to make informed eating decisions to help end the international epidemics of obesity, tooth decay, heart disease, diabetes and other conditions caused by poor food choices.

The study said new regulations should ban the use of added sugars and sweeteners, limit sugar and sodium content, and ban deceptive marketing and labeling practices. Pictured is one of the products that did not meet WHO nutrition and marketing standards: Hipp Organic Apple And Pear For Babies from 4 Months Onwards by Hipp

WHO guidelines say that babies and young children should not be given foods high in sugar, salt and trans fats or drinks containing sugar or sugar-free sweeteners. In the photo, one of the products that did not meet WHO nutrition and marketing standards: Aptamil organic banana and strawberry porridge for babies 6 months and older, from Danone.

WHO guidelines say that babies and young children should not be given foods high in sugar, salt and trans fats or drinks containing sugar or sugar-free sweeteners.

They add that consumption of 100 percent fruit juice should be “limited.”

In response to the study’s findings, a Kraft Heinz spokesperson said the company was committed to “manufacturing high-quality, affordable foods” in accordance with “international food standards and local laws and regulations.”

It also supports “the WHO recommendation that babies be exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life, followed by the introduction of nutritionally adequate and safe complementary foods,” they added.

They said: “We are committed to transparent communication around the nutrition of all our products, allowing consumers to make informed decisions that meet their lifestyle needs and preferences.”

Meanwhile, a Nestlé spokesperson added: ‘We share the same goals as ATNI to accelerate sustainable access to nutritious food.

‘We also support independent benchmarking which can help differentiate between practices within an industry.

‘However, the approach taken by ATNI does not produce these positive results. The methodology adopted may unfairly penalize companies with a significant portfolio.

“Wherever we operate, we comply with all local regulations, as well as our Nestlé Policy for implementing the Code, whichever is stricter.”

A Hero spokesperson said: ‘All products marketed by Hero, including in the UK, comply with local legislation regarding safety and nutritional requirements.

“In addition, Hero adheres to internal nutrition and safety standards that exceed current regulatory requirements.”