Donald Trump said the justice system and the United States “as a whole” are “under attack” after his family business was fined $364 million for fraud in New York.

The former president called Attorney General Letitia James “racist” and attacked the city, where he has $690 million in real estate, to try to “throw him out.”

The 77-year-old said he helped New York through “the worst of times” with his businesses and is now “overrun by Biden’s violent immigrant crime.”

Donald Trump said the justice system and the United States “as a whole” are under attack after his family business was fined $364 million for fraud in New York.

He turned to his Truth Social account after Judge Arthur Engoron released the devastating ruling barring him from being CEO of a New York company for three years.

His children Don. Jr and Eric were also fined more than $1 million each and suspended for two years.

Trump, whose wealth Forbes estimates at $2.5 billion, now has 30 days to come up with the money or present a $35 million bond.

He will likely appeal the verdict, which would have devastating consequences for his real estate empire not only in the Big Apple but around the world.

His children Don. Jr and Eric were also fined more than $1 million each and suspended for two years.

Trump, whose wealth Forbes estimates at $2.5 billion, now has 30 days to come up with the money or present a $35 million bond.

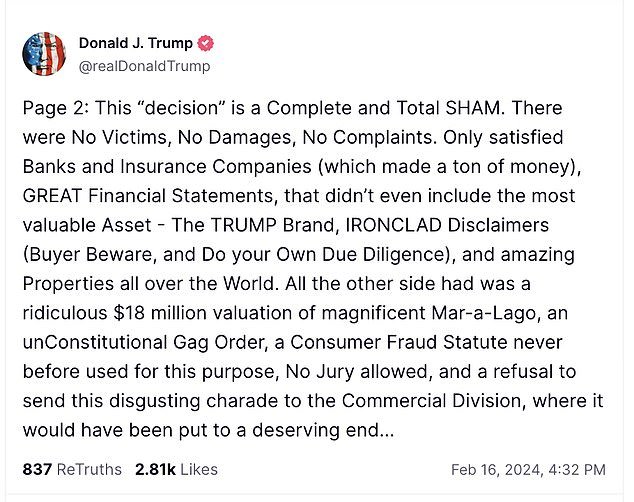

‘The justice system in New York State, and in the United States as a whole, is under attack by partisan, misled and biased judges and prosecutors.

‘Racist and corrupt Attorney General Tish James has been obsessed with “getting Trump” for years and used corrupt New York State Judge Engoron to obtain an illegal and un-American judgment against me, my family and my tremendous business.

‘I helped New York City during its worst times, and now, as it is overrun by Biden’s violent immigrant crime, radicals are doing everything they can to kick me out.

‘A corrupt New York state judge, working with a totally corrupt Attorney General who ran on the basis of “I’m going to get Trump,” before knowing anything about me or my company, just fined me $355 million on the basis of only in having built A GREAT COMPANY. ELECTORAL INTERFERENCE. WITCH HUNT (more to follow!).’

Trump has up to 30 days to get the money, which with interest could exceed $400 million, or secure bail of around $35 million.

The stunning decision comes after an explosive three-month court case in which Trump took the stand and his children, including Ivanka, testified.

Trump now has more than $454 million toward judgments in New York after a jury ordered him to pay for defaming his rape accuser, E. Jean Carroll.

His net worth is believed to be around $2.6 billion, according to a Forbes estimate from September 2023, with the majority of his assets tied to his growing real estate and golf empire.

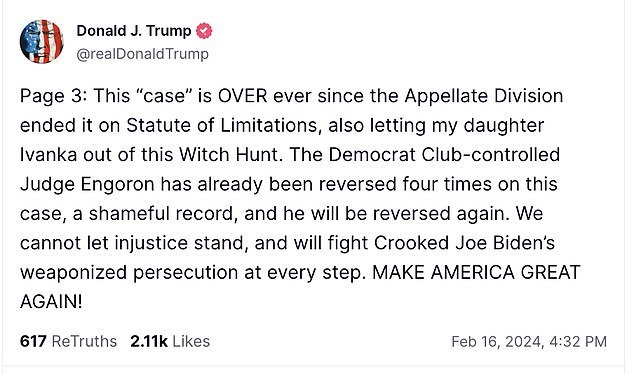

Former President Donald Trump sent out a series of Truth Social posts on Friday afternoon criticizing the ruling.

The Republican presidential front-runner, according to Forbes, has $640 million in cash and assets and $870 million in golf clubs and resorts.

His New York real estate holdings are worth $690 million and his branding and social media businesses are worth $160 million.

The Trump Organization called the ruling a “serious miscarriage of justice,” accused New York Attorney General Letitia James of “overreach” and said Deutsche Bank made “hundreds of millions” doing business with them.

‘All members of the New York business community, regardless of industry, should be seriously concerned about this blatant overreach and this brazen attempt by the Attorney General to exercise unlimited power where no public or private harm has been established.

“If allowed to stand, this ruling will only further accelerate the continued exodus of businesses from New York.”

Engoron had already found Trump, and his sons Don Jr. and Eric, liable for fraud and the trial was to determine how much they should pay.

James had demanded more than $370 million from Trump and to be banned from doing business in New York state.

James accused Trump and family businesses of exaggerating his net worth by billions of dollars.

An aerial view of former President Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate on August 10, 2022 in Palm Beach, Florida. How much is Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago property worth? That has been a point of contention after a New York judge ruled that the former president exaggerated the value of the Florida property when he said it is worth at least $420 million and perhaps $1.5 billion.

Trump has been represented by his passionate lawyer Alina Habba. On Thursday he admitted that he did not have “high hopes” for the verdict.

She sought to permanently ban Trump from participation in New York’s real estate industry and sharply limit his ability to do business in the state.

During the case, Trump lashed out at James, an elected Democrat, calling him partisan, “racist” and “corrupt.”

He also had an ongoing dispute with Judge Engoron and his clerk, which led to the former president being placed under a gag order.

In his closing arguments on Jan. 11, Trump defied the judge and delivered a six-minute tirade after his lawyers spoke.

“I am an innocent man,” Trump protested. ‘I’m being pursued by someone (James) who is running for office. What has happened here, sir, is a fraud to me.

Trump said he was being attacked by officials who “want to make sure he doesn’t win again.”

Judge Engoron told Trump’s lawyer, Chris Kise, to “control your client.”