Pep Guardiola is a pretty big name in football and for a while he was also part of the discussions in anti-doping circles.

In a moment we will get to what Gary Neville and Roy Keane expressed about their suspicions about the Italian opposition in their matches for Manchester United in the mid-2000s. But first we should address the popular fallacy that football and drugs for improving performance share a less complicated relationship than other corners of the athletic sphere.

We will highlight here that a failed test in sport does not necessarily mean cheating, but the broader point is that a failed test in football, proven or not, does not carry the same reputational stigma that it carries elsewhere. Not even close.

Guardiola certainly not and his was a particularly interesting case. He tested positive twice for the steroid nandrolone in 2001, when he played for Brescia in Italy.

Among other consequences of that saga, he was given a seven-month suspended prison sentence, but he maintained his innocence, contested the findings, lost an appeal that had been based on a pollution defense and then, in 2009, was acquitted by the courts. . of any irregularity.

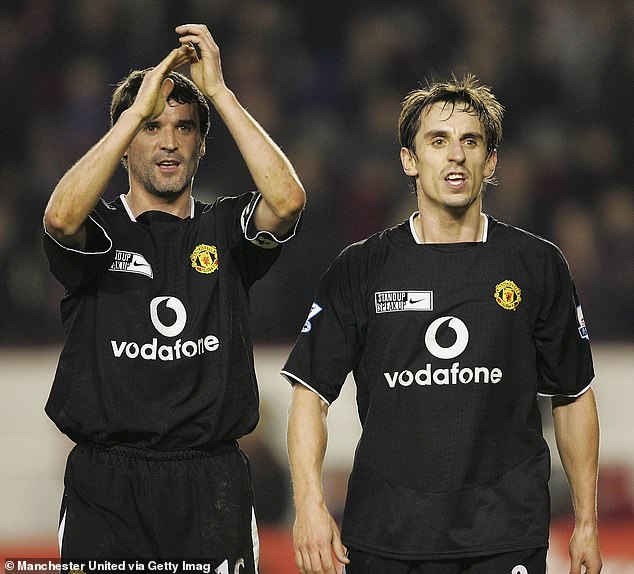

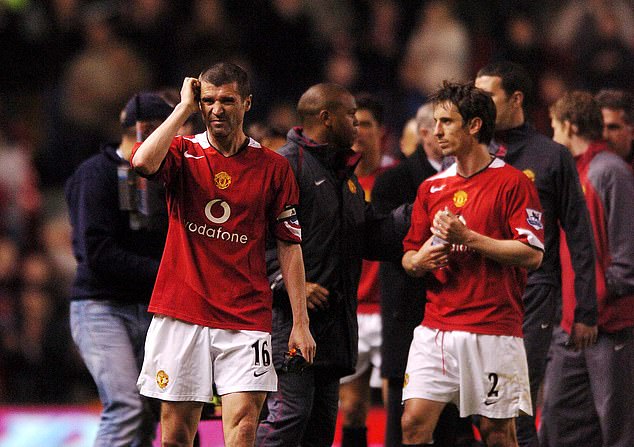

Former Man United stars Gary Neville and Roy Keane claim some teams they faced were not ‘clean’

Neville and Keane’s comments highlight that football has a strange relationship with doping, where a failed test does not carry the same reputational stigma as elsewhere.

Pep Guardiola tested positive twice for the steroid nandrolone when he was at Brescia in 2001, but mud doesn’t stick in football like it does in other sports. He maintained his innocence throughout

The detail of his pardon was fascinating: during this long process, Guardiola’s defense morphed into an argument stemming, in part, from “unstable urine” and whether such old samples could be trusted or even reanalyzed. It was established that they could not.

Today we are talking about one of the best coaches in the history of sports, not about the stability of his urine sample. When was the last time you heard about that episode?

None of this is meant to question his innocence, but it does illustrate that mud doesn’t stick in football. There are no longer those rumors in the corners about Guardiola, which, rightly or wrongly, is not a luxury enjoyed in other sports.

Sir Mo Farah or Sir Bradley Wiggins have never tested positive but have been dogged by innuendo due to events and associations in their careers.

Much more so than Dutch stars Edgar Davids, Frank de Boer and Jaap Stam, who showed poor signs and served suspensions that were reduced after their claims about accidental ingestion were accepted. Perhaps it is because the accusation of doping in football rarely persists, or because the noise around such cases is simplified and silenced, that the idea that the sport does not have a doping problem has taken hold.

I mentioned this to a prominent figure in the anti-doping community shortly after Paul Pogba tested positive for DHEA, which helps the body produce other hormones, such as testosterone, last year, and he had a good laugh at the idea.

The common argument is that it is a skill game. Gary Lineker went there a few years ago and said: “Doping is not really a problem in football.” Doping does not help players play better.” He later accepted it as naïve, as he had been, because football is much more than a game of skill.

It’s a catch-up game. It’s about being fit to play again and being able to run harder for longer, which is what Neville and Keane noticed in their encounters with Italian teams.

“I was leaving and I was absolutely devastated and I remember that,” Keane recalled on his podcast, Stick to Football. “I looked at players I played against, a couple of Italian teams, and it looked like they hadn’t even played a game.”

Neville added: “When you look back and see what came next in cycling and other sports, and in doctors, you think: ‘Wait.’

“We thought at the time (and we were fit, we weren’t drinkers) that something wasn’t right. We once walked off the field against an Italian team and thought, “That’s not right.”

“I know a couple of guys, from the mid-2000s, who thought exactly the same thing.”

Keane and Neville reflected on their particular suspicions when playing against Italian teams

Paul Pogba’s case at Juventus is still unknown after he tested positive for DHEA

Nobody knows why it would be a big surprise. Neither Keane nor Neville mentioned names or clubs, but it is a public fact that in 2004, Juventus doctor Riccardo Agricola received a 22-month suspended prison sentence for supplying a performance-enhancing drug. He was subsequently acquitted on appeal.

The trial examined the club’s practices from 1994 to 1998, during which they were three-time Italian champions and European champions in 1996, and a time when then-Roma coach Zdenek Zeman said Italian football needed “leave the pharmacy.”

It would be easy to talk about an Italian sporting culture, where so much doping has occurred, but we can also look closer to home.

A Mail on Sunday report by Edmund Willison found that at least 15 Premier League footballers tested positive for drugs between 2015 and 2020 and none of them received any kind of ban.

Twelve of them tested positive for banned performance-enhancing substances.

It could be the case that football has a bigger problem than it wants to acknowledge. Or that every positive is an accident. Maybe, but you wouldn’t bet a jar of unstable urine on any other sport, so why this one?