A prominent royal historian has condemned palace aides advising the Prince and Princess of Wales in the wake of the embarrassment caused by their Mother’s Day photograph.

Tom Bower told The Reaction that the private secretaries who give the monarchy strategic guidance to prevent a crisis are all ‘Yes men’ who are failing the family.

He told hosts Sarah Vine and Andrew Pierce that the royals are ‘sliding into crisis’ due to ‘an erosion of good advice’.

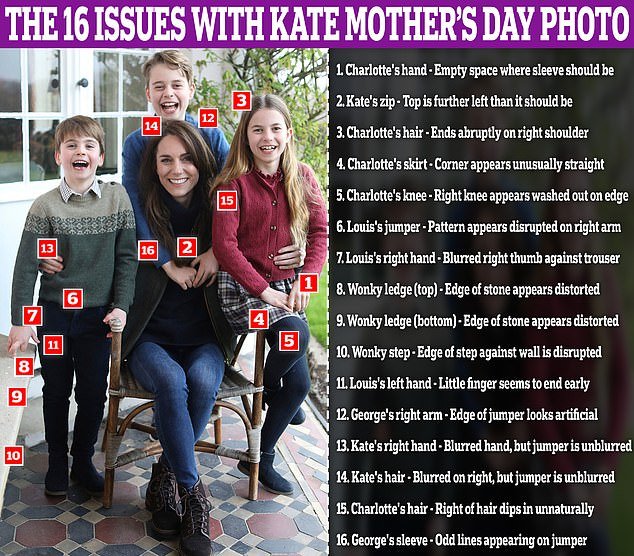

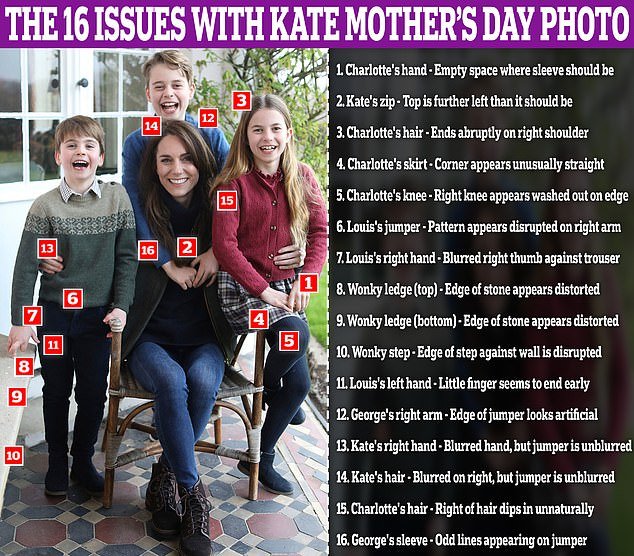

Sir. Bower’s strong warning to the royal family comes after a “tumultuous” week in which Princess Kate apologized for a photoshopped picture of her published on Mothering Sunday.

Ms Vine shared her own concerns: ‘It’s just ironic that a picture designed to undo all the mad conspiracy has made it much worse.

Tom Bower (pictured) told The Reaction that the private secretaries who give the monarchy strategic guidance to prevent a crisis are all ‘Yes men’ who are failing the family

He told hosts Sarah Vine and Andrew Pierce (pictured) that the royals are ‘sliding into crisis’ due to ‘an erosion of good advice’

On Sunday, Kensington Palace released the first photo of the Princess of Wales since the operation

“There’s another weird thing about the picture, which is that she’s not wearing her wedding ring.”

Sir. Pierce agreed, adding, “her hands could have been covered up quite easily.”

Prince William took the picture of his wife with their children, but Kate was forced to admit she photoshopped the image when international photo agencies issued a kill order.

They did this because they could see that it was edited and therefore violated the rules of what can be used officially.

But the author of ‘Revenge: Meghan, Harry, and the War between the Windsors’ claimed Kate was let down by her aides and ‘shouldn’t be blamed at all’.

Mr. Bower said the shoot was meant to end rumors about Kate’s health following her stomach surgery in January.

Coupled with the king’s cancer diagnosis, there are fears the monarchy is at its weakest for years with so few working royals.

Sir. Bower said: ‘I don’t think we should blame the princess at all.

William and Kate were spotted leaving Windsor for Westminster Abbey yesterday afternoon

Kate usually wears her wedding ring and an engagement ring that once belonged to Princess Diana

Kate was last seen at a royal event on Christmas Day 2023 with her family in Sandringham

‘She is recovering from a serious operation and I think she was pressured to do this photo shoot because people thought it would stop the terrible ghouls on social media.

‘The private secretaries in both Kensington Palace and Buckingham Palace are just not up to the task.

‘I think what we are seeing is the erosion of good advice because the King himself has always only wanted to be advised by ‘yes men’.

‘I fear that Prince William is also going the same way.

‘William seems to like weak people in his court and this cannot continue. We are dealing with a royal crisis of people; they are sick, they are old, and there are very few of them.

‘They should have brought in a professional Press Association photographer and that would have been the end of it.’

Speaking about the missing wedding ring, Mrs Vine added: ‘Whoever is advising them is not doing their job because if I was advising them I would have said this is a lovely photograph of you and your children but you are not having your wedding on. ring.

‘Are you sure this is what you want to post?

‘I actually feel very sorry for the Princess of Wales… the problem is the way it’s been handled has just made it a lot worse and now there’s a layer of mistrust creeping in.’

Also debated in this week’s episode is the news that Boris Johnson may appear on the campaign trail as Rishi Sunak tries to prevent an election wipeout.

The reaction is published every Wednesday and is available on the Daily Mail’s YouTube channel.