Rachel Reeves says the UK’s fiscal situation is so bad that she will have to raise taxes in the October budget. Well, since she’s said she will, we should expect that to happen.

But in reality the country’s economic situation is improving so rapidly that there will probably be no need to raise taxes at all.

We had three batches of new information last week.

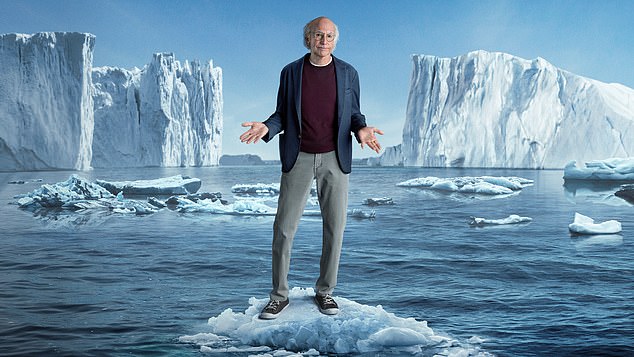

Curb your fiscal enthusiasm: Despite Rachel Reeves’ cool assessment of the UK economy, things aren’t all that bad, says Hamish McRae

One of them was the statement about an alleged £22bn-a-year black hole in the Government’s finances, and this suggestion of higher taxes to plug it.

The second was the cut in interest rates by the Bank of England.

Third, the Bank’s forecast for economic growth for this year was improved, doubling it to 1.25 percent.

As for the black hole, that £22bn a year would have to be offset by government revenues estimated at £1,095bn in the last financial year and £1,150bn this year. So even if you accept the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s argument, it is not a huge figure in relative terms.

However, these figures will improve thanks to the other two new elements.

Lower interest rates will reduce the cost of servicing the national debt, and faster growth will increase tax revenues.

In the last financial year, the government’s interest bill was £102bn. It is difficult to estimate exactly how much cutting rates will reduce that cost, because other factors, such as changes in government bond yields and the retail price index (which affects inflation-linked government bonds), cloud the picture.

However, on Friday the yield on 10-year government bonds was around 3.8 percent, down from 4.4 percent a year ago.

The government, like mortgage holders, can expect lower interest rates.

Debt servicing costs in June were the lowest for that month since 2020, and I can see at least £10bn coming out of the total bill for the year.

By the way, two-year government bonds are now at 3.7 percent, while a year ago they were at 5 percent.

Since government bond yields directly affect fixed-term mortgage rates, anyone looking for a two-year solution is in a better position than they were last year.

It is also difficult to estimate how much further tax revenues will increase as a result of faster-than-expected growth.

I think the Bank of England, like other official forecasters, continues to underestimate the economy’s performance this year, and that we will eventually learn that growth turned out to have been even stronger.

However, it doesn’t take a math genius to figure out that if the economy is 1 cent larger than originally thought, tax revenues will likely be at least 1 percent higher, too.

Not only can the government expect an extra £10bn in revenue, probably more, but with more people in work its welfare bill is likely to fall too.

None of this is to say that the state of our public finances is brilliant. The size of public debt as a proportion of national output is the second lowest in the group of seven leading economies, after Germany.

But at just under 100 percent of gross domestic product, it is at its highest level since the 1960s, when we were still paying the cost of World War II.

The Office for Budget Responsibility has projected this year’s budget deficit to be 3.1 percent of gross domestic product, which is too high.

All I’m saying is that things have gotten better in the last few months, not worse, and since they’re on track to get even better for the rest of this year, there probably won’t be a need to raise taxes in October.

So why do it? You could be cynical and say that it is the classic trick new CEOs use when they take up a job.

Claim that your predecessor made a mess, remove all the bad news, and that will make your own performance (and your stock options) look much better.

If I wanted to be kind to Reeves, I’d say he’s being cautious, there are a lot of uncertainties, and he wants to create a margin of safety.

There is, however, a danger: bombarding ourselves with even more taxes harms growth.

I hope this new group is aware of this, but I’m afraid not.

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them we may earn a small commission. This helps us fund This Is Money and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationships to affect our editorial independence.