A judge has dismissed a defamation lawsuit filed by a Los Angeles bachelor against more than 50 women after he discovered they were talking about him in a Facebook group called ‘Are We Dating the Same Guy?’

Dozens of women called Santa Monica’s Stewart Lucas Murray a “bad date” before he made the decision to sue following allegations that he was labeled a murderer and accused of having STDs on the forum.

But a judge in downtown Los Angeles ruled in favor of defendant Vanessa Valdez.

The women argued that they had done nothing wrong by posting their personal opinions in a private online group on social media.

The judge found no evidence of conspiracy by the women and granted an Anti-SLAPP motion, which protects those who speak out on matters of public interest against abusive lawsuits made to silence them.

Stewart Lucas Murray of Santa Monica attempted to sue dozens of women who he claims defamed him through Facebook posts. His lawsuit has now been dismissed by a Los Angeles judge.

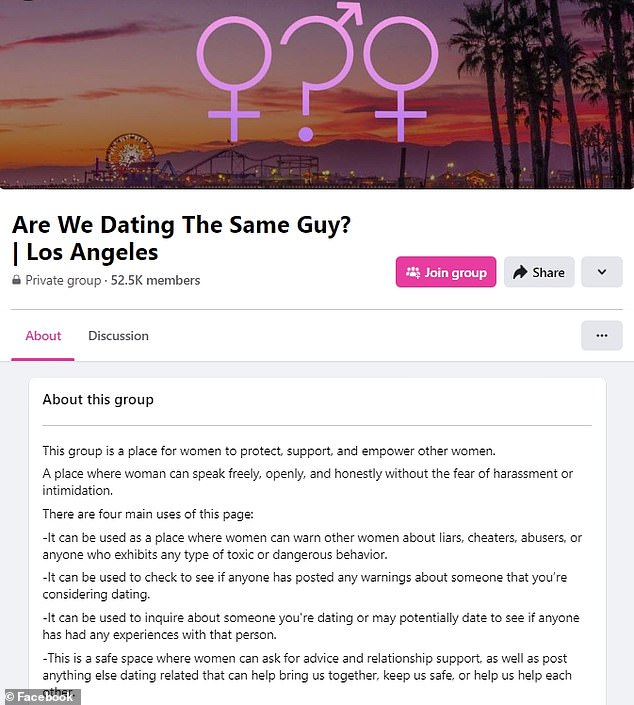

The lawsuit stems from the social media group, which currently has more than 52,500 members, where daters issue warnings about potentially harmful or deceptive men.

“It just feels great to have all the charges dismissed, it wasn’t just the two defamation charges, but all 11 charges were filed against me,” Valdes said during a news conference Monday.

“We will all have several Anti-SLAPP hearings in the coming weeks and we obviously hope that with Vanessa’s ruling it will set the precedent for the following hearings,” said another defendant, Olivia Berger.

The judge also reportedly concluded that, based on the evidence presented, the court saw no chance of Murray winning against the defendants on any claims he made.

It comes after the Yale-educated academic last month attempted to sue dozens of potential suitors after claiming he was the subject of false and defamatory posts and comments about him in the group.

He planned to sue on a host of charges including defamation, discrimination based on sex, intentional infliction of emotional distress, defamation and invasion of privacy, among others.

The lawsuit arose from the Los Angeles-specific private social media group, which has more than 52,500 members.

It is labeled as a place where daters can highlight any warnings about potentially harmful and deceptive men.

Murray had alleged that the women posted a variety of false statements about him, including claims that he had lied about being a lawyer, had tried to swindle them of money and had sexually transmitted diseases.

He also noted that the post made more serious claims, including that he was facing several charges of domestic violence, as well as being a murder suspect and being involved in a homicide case.

Murray has denied all claims, claiming he only remembers meeting one of the women “for less than 15 minutes.”

Murray started a GoFundMe page where he claimed he had briefly met one of the women, saying, “When I saw them on TV doing a press conference about me, it was the first time I saw most of their faces.”

But in a GoFundMe post last month, Murray alleged he had matched with a woman on a dating app before giving her his phone number and then quickly blocking her when he became suspicious of her photos.

“Instead of going their separate ways, he posted about me in some of these Facebook groups, obsessively searching for information, posting his own original post about me several times in a year, and then calling me a ‘viral’ guy,” he said.

He went on to claim that he had never met the woman in real life and that “the first time I saw her face was on TV when she was involved in a press release about me.”

According to the bachelor, at least 238 Facebook accounts posted his photos in the group, tracked his location and made up stories about his encounter.

‘Let me reiterate: I have never met most of them in my life. I’ve barely spoken to any of them, if ever. “I only remember meeting one of them and her for less than 15 minutes before I left,” Murray added.

‘Any minimal interaction with them was abruptly cut short by my quick rejection. When I saw them on TV to give a press conference about me, it was the first time I saw most of their faces.

The furious bachelor accused several women of “relentless” and “hateful cyberbullying” before his case collapsed.

Since then, he has raised more than $5,450 of his $60,000 goal through his personal fundraising, which he says will go toward “the vast amount of legal fees, damage experts, deposition expenses, investigation and time to deal with an overwhelming amount of work against multiple defendants. ‘.

One of the defendants, Valdes, revealed that she had connected with Murray on Hinge.

She said KTLA journalists last month: “From the beginning, [he] He gave me his phone number and said, “Let’s hang up.”

‘I commented with a message saying “bold move” with a happy face and then came a flood of harassing messages. So I immediately blocked him and reported him.’

The judge ruled in favor of the accused Vanessa Valdés, who revealed that she had connected with the Hinge bachelor

Vanessa claimed that it wasn’t until years later that she commented on a post about her exchange with Murray.

The lawsuit claimed that Murray had consistently attempted to join the group to defend himself, but was denied access.

Are we dating the same guy? The Facebook page has a lengthy description that reads: “This group is a place for women to protect, support and empower other women.”

‘A place where women can speak freely, openly and honestly without fear of being harassed or intimidated. There are four main uses of this page.

‘It can be used as a place where women can warn other women about liars, cheaters, abusers, or anyone displaying any type of toxic or dangerous behavior.

‘It can be used to check if anyone has posted a warning about someone you are considering dating.

‘It can be used to ask about someone you are dating or could potentially date to see if anyone has had any experiences with that person.

“This is a safe space where women can ask for relationship advice and support, as well as post anything else dating-related that can help us come together, stay safe, or help each other.”