For years, chronic fatigue syndrome has been ruled out as being exclusively related to the mind.

But new research ruled today that the disease, also called myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), is real.

Scientists have found, for the first time, key differences in the brain and immune system of CFS patients.

It suggests that the fatigue of the controversial condition, which can be debilitating, is due solely to a “mismatch” between what a patient’s brain believes it can achieve and what their body can actually achieve.

Experts hope the discovery, made by scientists at the US government’s National Institutes of Health, could lead to the development of treatments for the currently incurable condition.

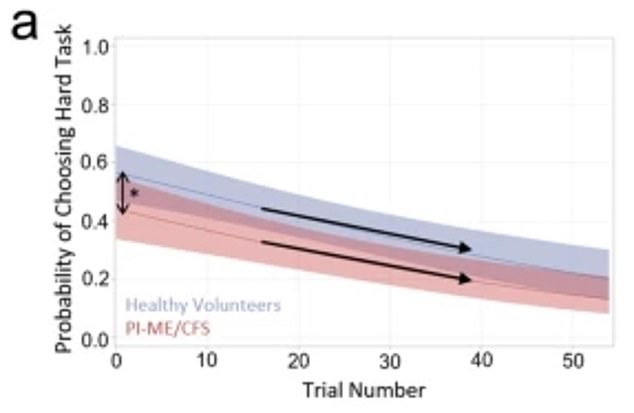

This graph shows the probability that CFS patients in the study (red) chose to perform a difficult task compared to healthy volunteers (blue) over the course of multiple trials. CFS patients were less likely to choose difficult tasks and over the course of trials

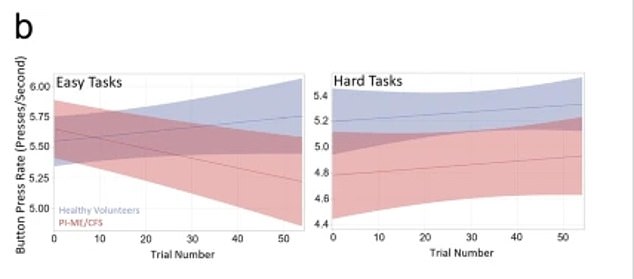

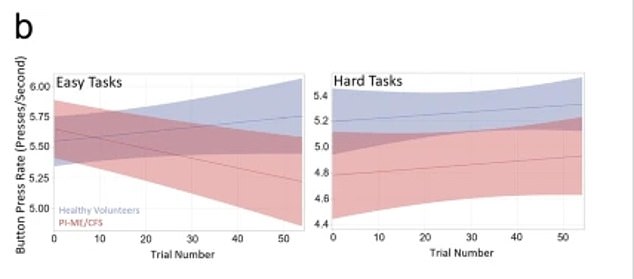

These graphs show results for button press rates, that is, how quickly participants could press a button in tests designed to measure fatigue. CFS patients (red) tapered off faster and performed fewer presses overall compared to healthy volunteers (blue)

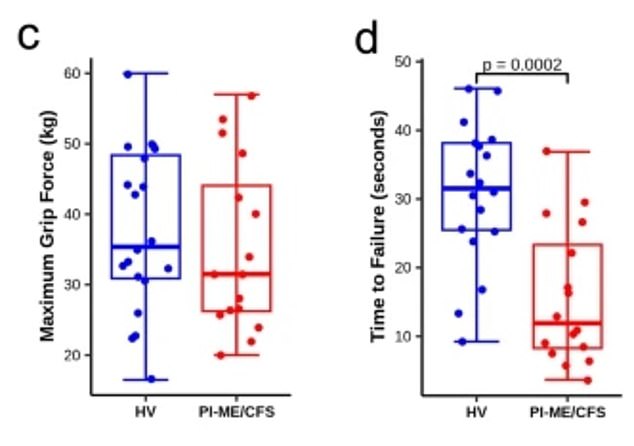

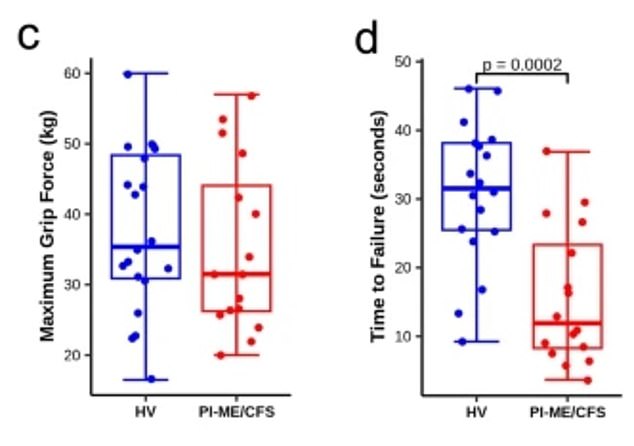

Graphs showing the results of a maximal grip strength test and time to failure among both CFS patients (red) and healthy volunteers (blue). The boxes show the average performance range, while the thicker vertical lines show the maximum and minimum values recorded.

Dozens of scientists conducted multiple experiments over five years on 17 patients, comparing their results to 21 healthy controls matched for age, sex, and body mass index (BMI).

This included taking MRIs of people who were asked to perform repetitive tests in which they held a device to measure how their brain responded to fatigue.

CFS patients showed less activity in the temporal-parietal junction, a key part of the brain for exerting effort.

Therefore, experts now theorize that disruption in this area is what is behind the telltale fatigue.

The scientists also compared cerebrospinal fluid samples between the two groups of patients and again found key differences.

A comparison of immune systems also showed that CFS patients had lower levels of memory B cells.

They are a part of the immune system designed to remember foreign substances, such as bacteria or viruses, to ensure that the body has longer-term protection and is not at risk of getting sick repeatedly every time a person encounters them.

Dr. Avindra Nath, an NIH neuroimmunology expert and lead author of the study, said: “We believe that immune activation is affecting the brain in several ways, causing biochemical changes and downstream effects such as motor, autonomic and cardiorespiratory dysfunction.”

Fellow researcher Dr Brian Walitt added: “We may have identified a physiological focal point of fatigue in this population.”

“More than physical exhaustion or lack of motivation, fatigue can arise from a mismatch between what someone believes they can achieve and what their body performs.”

Although the study is small, the researchers hope that their findings, published in Nature Communicationscan be replicated in a larger group.

If so, it could form the basis of new treatments for the syndrome.

Experts praised the study as an important and much-needed piece of comprehensive research for this still poorly understood disease.

Dr Karl Morten, a CFS researcher at the University of Oxford, said the results raised more questions that needed investigation.

“The brain appears to be potentially driving the patient’s response,” he said. ‘The big question is why? Is something still happening that we are not yet aware of?

Others cautioned that the data, while promising, “cannot highlight the causes.”

Dr. Katharine Seton, a research scientist at Quadram Institute Bioscience, said the new study represents a welcome change in CFS research.

“Historically, studies investigating ME/CFS have often focused on singular aspects of the disease,” he said.

‘However, the current article stands out for its extensive list of authors, in which experts from various disciplines collaborate to bring these pieces together and reveal a more complete picture.

“This interdisciplinary approach is crucial to improving our understanding of this disease.”

A groundbreaking US study may have uncovered the mechanisms behind the much-maligned and misunderstood chronic fatigue syndrome (file image)

All of the CFS patients in the study developed the syndrome after a viral or bacterial infection.

These infections are just one of the theoretical triggers of CFS. Others include problems with the immune system, a hormonal imbalance, or a genetic risk factor.

Four years after the conclusion of the study, four patients recovered spontaneously.

The study did not discuss the reasons or whether these patients had any specific results.

The symptoms of CFS vary from patient to patient and over time.

The most common include extreme physical and mental tiredness that does not go away with rest, as well as problems sleeping and with thinking, memory, and concentration.

Other symptoms include muscle or joint pain, sore throat, headaches, flu-like symptoms, dizziness and nausea, as well as a fast or irregular heartbeat.

In its mildest form, CFS sufferers can perform everyday activities with difficulty, but may have to give up hobbies and social activities to rest.

Patients with more severe CFS are essentially bedridden and may receive full-time care without being able to feed themselves, wash themselves, or even go to the bathroom without assistance.

One of the biggest challenges with CFS is obtaining a diagnosis due to the lack of tests that can prove that the patient has it.

With no such testing currently available, patients are forced to undergo diagnosis through a process of elimination, with doctors progressively ruling out other conditions until CFS is the only one left.

There is currently no cure for CFS. Instead, treatment revolves around therapy, lifestyle changes, and the use of some medications to relieve symptoms.