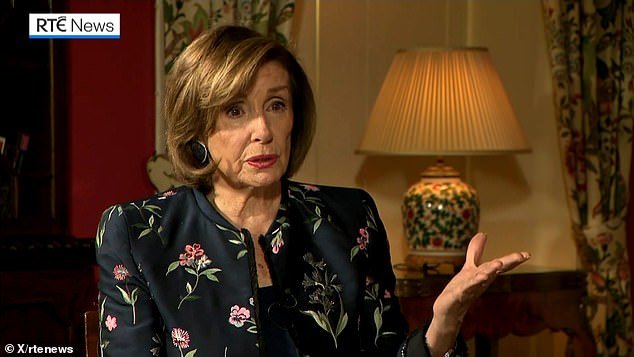

- Pelosi gave an interview in which she described Netanyahu’s response as “terrible.”

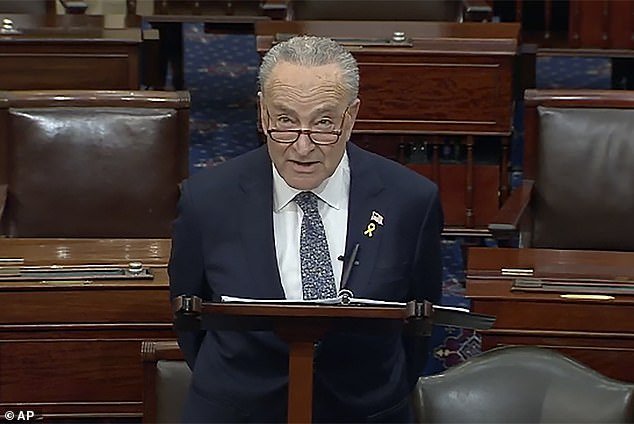

- He joined Senator Schumer, who called for new leadership in Israel last month.

- House passed relief bill with bipartisan support despite criticism of Netanyahu

- The foreign aid package advances in the Senate

Former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi criticized Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu as an obstacle to a two-state solution and said he should resign.

He joins a growing list of prominent Democrats who have harshly criticized the Israeli leader or called on him to resign over his handling of the war in Gaza.

‘We recognize Israel’s right to protect itself. We reject Netanyahu’s policy and practice,’ Pelosi said during an interview with the Irish newspaper RTE News. ‘What could be worse than what he has done in response?’

Pelosi called it “terrible.” He said his intelligence official resigned, but that he “should resign” since Netanyahu is “ultimately responsible.”

During the interview, the veteran California lawmaker was asked if Netanyahu is a “bloc” for peace.

“Well, it has been for years,” Pelosi said. “I don’t know if he is afraid of peace, he is incapable of achieving peace or he just doesn’t want peace.”

“It has been an obstacle to the two-state solution,” he added. ‘I highlight the word solution’.

Former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said in an interview with RTE News that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu should resign.

Pelosi called Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu an “obstacle to the two-state solution.”

Protesters in Tel Aviv demonstrate in favor of a hostage deal with Hamas and against the Israeli prime minister on April 20, 2024.

On Tuesday, the Senate voted to advance a foreign aid package that includes $26 billion for Israel and humanitarian aid for the people of Gaza.

Over the weekend, the House passed the bill, ending a months-long impasse.

But despite supporting aid to Israel following the Hamas terrorist attack on October 7, some Democratic leaders have sharply criticized Netanyahu’s leadership.

More than 34,000 Palestinians have been killed and more than 77,000 injured since Israel declared war on Gaza.

Last month, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.), the highest-ranking Jewish official in the United States and a close ally of Israel, said he believes Israel should hold new elections once it end the war in Gaza.

He delivered a scathing criticism of Netanyahu, saying he had placed himself in a coalition with “far-right extremists” and warned that “Israel cannot survive if it becomes a pariah.”

Democratic Senator Chuck Schumer on March 14 called for elections and new leadership in Israel because Benjamin Netanyahu is an “obstacle to peace,” in some of the most scathing criticism of the United States since the October 7 Hamas attack.

Debris from destroyed buildings in the southern Gaza Strip on April 23, 2024

President Biden also criticized Netanyahu’s response in Gaza, calling his approach to the conflict a “mistake.”

But the Biden administration remains committed to supporting aid to the United States’ closest ally in the Middle East.

Democrats’ criticism of the Israeli leader comes as protests have spread across the country over Israel’s response.

On university campuses, pro-Palestinian protesters have been camping out and tensions continue to rise.

At Columbia University, in-person classes will move online until the end of the spring semester.

Republican President Mike Johnson is expected to travel to Columbia on Wednesday to meet with Jewish students, as some have expressed fear and feel unsafe amid reported growing hostility on campuses.