Democrats see Florida as a state where they can make progress, as it is about to have one of the strictest abortion bans in the country and abortion rights will be squarely on the ballot there in November.

The Florida Supreme Court on Monday upheld the state’s 15-week abortion ban, clearing the way for a six-week ban to take effect in 30 days. It often takes six weeks before a woman knows she is pregnant.

The ruling was met with outrage by Democrats and abortion rights activists in the state and nationally, but it could also be a galvanizing issue ahead of the November elections.

President Biden called the decision outrageous on Tuesday.

“Yesterday’s extreme decision puts desperately needed health care even further out of reach for millions of women in Florida and across the South,” the president said in a statement.

“This decision means that millions of women in Florida and throughout the Southeast will likely live in an even crueler reality in which they will have to choose between putting their lives at risk or traveling hundreds or thousands of miles to receive care,” the vice president said. Kamala. Harris, who has taken a leadership role on reproductive rights in the administration, in a separate statement.

Pro-abortion rights protesters in Florida in 2022 after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. On April 1, 2024, the state Supreme Court allowed an abortion measure to be placed on the ballot in November.

The State Supreme Court upheld Florida’s 15-week ban, paving the way for a six-week ban in the state.

At the same time, Florida’s highest court is allowing Floridians to have their say by allowing an abortion access measure to be on the ballot in November.

Following the monumental decision, President Biden’s campaign manager released a memo with the subject line “President Biden’s Opening in Florida.”

“As we have seen in election after election, protecting abortion rights is about mobilizing a diverse and growing segment of voters to help keep Democrats afloat at the polls,” wrote Julie Chávez Rodríguez.

He focused on the amendment officially presented on the November ballot.

‘President Biden and Vice President Harris and their commitment to fighting Donald Trump and Rick Scott’s attacks on reproductive freedom will help mobilize and expand the electorate in the state, as Floridians overwhelmingly support abortion rights.

In a call with reporters Tuesday, Rodriguez doubled down, saying Florida is “definitely” in play and that Democrats have multiple paths to 270 electoral votes that they have been able to keep open.

Democrats in Florida have the most hope they have felt in years, as the once clear battleground state has turned deep red in recent elections.

Biden speaking at a ‘Reproductive Freedom Campaign Rally’ in January. He called the Florida Supreme Court’s decision to uphold an abortion law in the state “outrageous.”

Vice President Harris became the first vice president or president to visit an abortion clinic last month. She has been a prominent abortion rights advocate in the Biden administration.

‘“In November, Florida voters will defend women’s freedom to make their most personal medical decisions by rejecting this abortion ban and removing Rick Scott from the Senate,” said Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee spokesperson Maeve Coyle of the Republican senator. of the state that is running for election this fall.

‘Florida is at stake and it’s worth fighting for!’ Democratic state Sen. Shevrin Jones wrote in X after the decision.

‘That’s how it is! Florida is at stake!’ wrote Nikki Fried, chairwoman of the state Democratic party and the last Democrat to hold statewide elected office.

‘Don’t give up on Florida. We can win this,” wrote March for Our Lives founder David Hogg.

“Florida just got a lot more expensive for the Republican Party,” wrote political strategist and former GOP insider Rick Wilson.

A University of North Florida poll last fall found that 62 percent of Florida voters indicated they would vote “yes” on a pro-abortion rights ballot measure, including a majority of Republicans.

The measure needs 60 percent support in November to pass.

Anti-abortion groups and Republican officials had opposed its inclusion on the ballot.

SBA Pro-Life America welcomed the Florida Supreme Court upholding the state’s abortion law, but criticized the inclusion of the ballot measure in November, claiming it would bring back “unsafe late-stage abortions.”

Supporters of the measure say it gives women the freedom to make personal medical decisions.

Anti-abortion protesters in Tallahassee, Florida, in May 2022

Scott’s opponent, Democrat Debbie Mucarsel-Powell, reacted by saying she’s not surprised the abortion measure is on the ballot and said Florida voters have an “independent streak” and don’t want government interference.

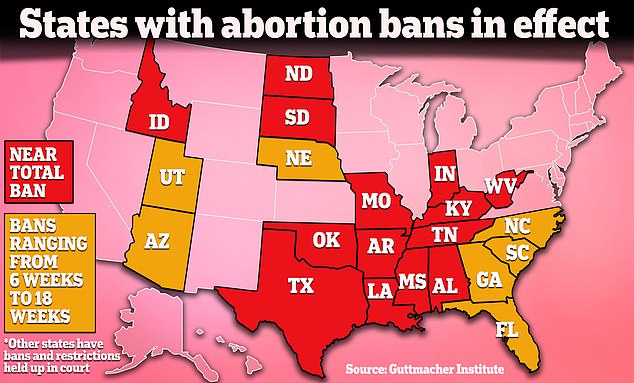

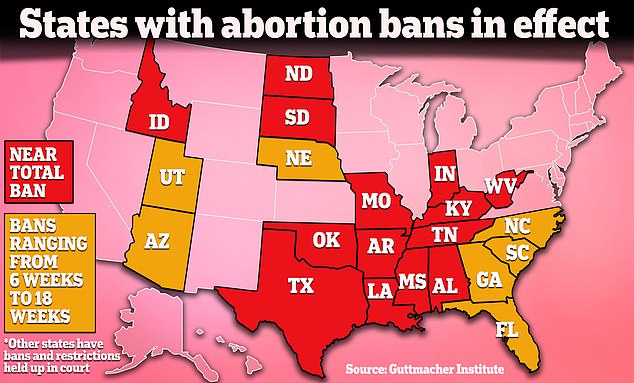

Abortion has been a mobilizing issue for Democrats since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v Wade in 2022 and returned the issue to the states.

Where abortion measures have been on the ballot, including in red states like Kansas and Ohio, voters have voted to protect access to abortion.

While Democrats openly criticized the Florida court’s decision to allow abortion laws and applauded the measure being on the ballot in November, Republicans have remained silent.

Gov. Ron DeSantis, who signed the six-week ban, has so far not publicly responded to the court’s decisions. Neither does Senator Rick Scott.

The abortion bans and ballot measure also put former President Trump’s comments on abortion back in the spotlight.

The former president has not definitively said where he stands on the national abortion ban as he campaigns for the White House. He previously indicated that he would support a 15-week federal ban, but his campaign Tuesday suggested otherwise.

“President Trump supports the preservation of life, but he has also made clear that he supports states’ rights because he supports the right of voters to make decisions for themselves,” senior adviser Brian Hughes said in a statement.

Trump previously called Florida’s six-week abortion ban a mistake, but also touted the overturning of Roe v Wade with the help of three Supreme Court justices he nominated.

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis speaks to supporters before signing the 15-week abortion ban in 2022. He also signed a six-week abortion ban in April 2023.

Trump has signaled he would support a 15-week federal abortion ban

The Biden campaign and the Democrats currently have a huge monetary advantage over the Republicans and Trump, and the Democrats are going on the offensive.

On Tuesday, the Biden campaign released a new reproductive freedom ad called ‘Confidence’ in which the president directly attacks Trump on camera over abortion.

While Democrats have been optimistic about what the inclusion of the ballot measure in Florida this November means for their chances, it has become a very red state, and Republicans have a huge lead with more than 855,000 more registered voters than the democrats.

Republicans have a supermajority in the state legislature and in all state executive offices.

Gov. Ron DeSantis crushed his Democratic opponent in 2022 by 20 points, and Republican Sen. Marco Rubio won his reelection bid that year by more than 16 points.

Trump won the state by just over three points against Biden in 2020 and scored a 1.3-point victory over Hillary Clinton there in 2016.

Florida has not elected a Democrat to state office since Fried won the Agriculture Commissioner race there in 2018.