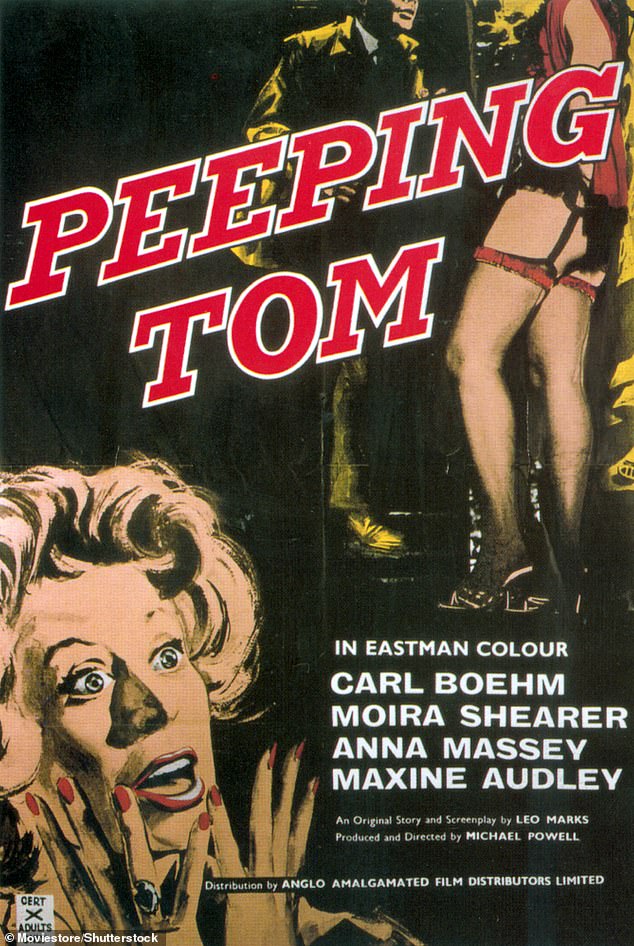

If ever a film was ahead of its time, it was British director Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom.

It was released in 1960, a year in which moviegoers were more accustomed to an endless diet of war movies, romantic melodramas and, from the United States, John Wayne westerns.

Therefore, a film centered on a serial killer, who filmed the terror of his victims in their final moments while repeatedly stabbing them with a sword hidden in his camera tripod, was always going to challenge audiences.

Add in a healthy dose of psychological torture, a shocking level of female nudity and a gruesome suicide and you have a recipe for critical outrage.

Within 24 hours of its London premiere, Peeping Tom became Britain’s most controversial and reviled film.

Powell was branded a sadist and pervert, and critics said his film should be thrown “quickly into the nearest sewer.”

If ever a film was ahead of its time, it was British director Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom.

In the decades following its release, Peeping Tom’s qualities were re-evaluated and it is now considered a masterpiece.

One was so outraged that he wrote: “Neither the desperate leper colonies of East Pakistan, nor the alleys of Bombay nor the sewers of Calcutta have left me with feelings of nausea and depression like…” . . Voyeur.’

Within a few days, it had been removed from theaters and Powell, until then revered author of classics such as The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), A Question of Life and Death (1946), Black Daffodil (1947) and The Red Shoes (1948), was thrown into outer darkness.

But in the decades that followed, Peeping Tom’s qualities were reevaluated and it is now widely considered a masterpiece. The British Film Institute named it the 78th best British film of all time, and in 2017, a Time Out magazine poll of 150 actors, directors, writers, producers and critics ranked it as the 27th best British film. .

And now, a lovingly restored version has been released on multiple formats, including DVD and Blu-Ray.

So what explains this extraordinary change of fortune?

Much of the credit for Powell’s rehabilitation (34 years after his death at age 84 in 1990) can be attributed to a Hollywood director who saw The Red Shoes when he was nine and never forgot the experience.

Martin Scorsese, no stranger to extreme violence in his own films such as Mean Streets and Taxi Driver, initially thought Powell was a pseudonym, but tracked him down in 1975, living “up to the limit” in a freezing cottage in Gloucestershire.

A man long accustomed to a whiskey at five in the afternoon was too poor even to afford his daily drink and had to chop his own firewood to provide a minimum level of heating.

When Scorsese came to Britain to attend the Edinburgh film festival to promote Taxi Driver, a mutual contact arranged to meet Powell at a London restaurant.

“He was very quiet and didn’t really know what to do with me,” Scorsese later recalled. “I had to explain to him that his work was a great source of inspiration for a whole new generation of filmmakers: myself, Spielberg, Paul Schrader, (Francis Ford) Coppola, (Brian) De Palma.”

Powell became an advisor to Scorsese, encouraging him not to compromise his vision for his mob classic Goodfellas, with its extreme violence and drug use, no matter how many studios rejected it.

The British Film Institute named it the 78th best British film of all time.

Powell was branded a sadist and pervert, and critics said his film should be thrown “quickly down the nearest sewer.”

A film centered on a serial killer, who filmed the terror of his victims in their final moments while repeatedly stabbing them with a sword hidden on his camera tripod, was always going to challenge audiences.

Even after more than 60 years, Peeping Tom still has the ability to surprise. The plot revolves around a fictional film technician named Mark Lewis, played by German actor Carl Boehm, who has a sideline taking pornographic photographs.

After hours, he murders women while filming their contorted faces and agonized gasps, and uses the footage to compile his own snuff films, long before the term was used. But we are also drawn into his complex mentality, as Lewis reveals his twisted upbringing at the hands of a sadistic father.

After meeting his neighbor Helen, who lives downstairs with her blind mother, he shows her black and white home movies, filmed by his psychologist father, of young Lewis being subjected to traumatic episodes as a child in order to continue with your investigation. This included filming him at his mother’s deathbed, with his father capturing his anguish.

In fact, he was under observation at all times as, in a chilling foreshadowing of the ubiquitous webcam, spy cameras had been installed throughout the family home.

At one point, we see Lewis screening his snuff film while Helen’s mother is in his apartment and realizes how distraught he is. Later, Helen herself watches one of the movies, but Lewis can’t bring himself to kill his future girlfriend to keep his secret.

Those looking for Freudian parallels between Powell and Lewis will be disappointed to learn that the director’s father was a hop grower, not a psychologist.

Powell introduced himself as Lewis’s father and his own son, Columba, played the young Lewis; That’s as far as the parallels end.

One reviewer observed: ‘In Peeping Tom, (Powell’s) self-exposure goes even further. Not only does he play the sadistic father, but he uses his own son as a victim.’

Powell’s third wife, Thelma Schoonmaker, Scorsese’s longtime cinematographer, has dismissed this interpretation, arguing: “I don’t think that ever crossed Michael’s mind…he didn’t take it that seriously.” He thought, “That’s a good idea, Columba will be a good actor and it will be fun for us to do it together.” I don’t think he expected the storm of reaction.

Even after more than 60 years, Peeping Tom still has the ability to surprise

Columba Powell, now 72, says: “Everyone thinks I should be traumatized, but it was a movie and real life was different.”

But the casting was not the only crossover between fiction and reality, because Michael Powell, the future director, was also an obsessive filmmaker at home. He relentlessly cataloged his family life with his second wife, Frankie, and his two children.

However, unlike the introspective psychopath Lewis, Powell was no timid violet. After leaving a banking career, he pursued a career in the film industry with relentless drive.

After taking on various backstage roles, he began working on Alfred Hitchcock’s early British films in the late 1920s.

In the 1930s, Powell directed his own low-budget films, but his big break came in 1939 when he met exiled Hungarian screenwriter and producer Emeric Pressburger.

In 1943, the pair made The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, starring Deborah Kerr, and five years later he and Pressburger earned an Oscar nomination for best picture for The Red Shoes.

However, by the mid-1950s, the two men were growing apart professionally, and more than one critic has speculated that it was the absence of Pressburger’s insight that explains Powell’s decision to make Peeping Tom.

Powell struggled to raise the film’s meager £125,000 budget but, strangely, Carry On financier Nat Cohen intervened, probably attracted by the film’s apparently obscene material. He would live to rue the day he did it.

Cohen and Powell weren’t the only ones to suffer backlash. Carl Boehm never made another film in English.

By contrast, Anna Massey, who played Helen, had a distinguished career. But if Powell was bitter, he didn’t show it.

Whatever his flaws, Powell’s voyeur painted a picture of what was to come.

With its flashy Technicolor and movie-within-a-movie premise, Peeping Tom marked the end of the postwar studio system and its strict moral code.

In the end, the irony of its rehabilitation as a cinema classic was not lost on Powell, who wrote in his autobiography: “I make a movie that no one wants to see and then, 30 years later, everyone has seen it or wants to see it.” Look at it.’