It was a defining moment in the miners’ strike of 40 years ago. An almost medieval pitched battle between thousands of police and pickets at the Orgreave coke plant near Rotherham in South Yorkshire proved to be a brutal and decisive turning point in British post-war industrial history.

Orgreave marked the beginning of the end not only of the bitter dispute but, ultimately, of deep coal mining in this country. The miners’ strike divided families and devastated local communities, many of which have not yet fully recovered.

Some, like nearby Cortonwood, were reinvented as retail parks. Shirebrook, another former pit town not far from the M1, is now home to a huge windowless warehouse run by Sports Direct.

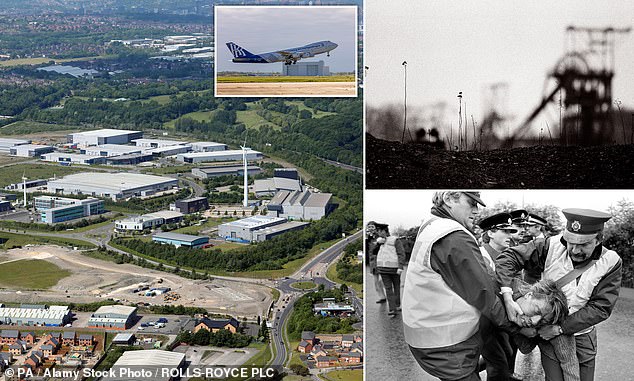

Fast forward four decades to Orgreave and the site, Yorkshire’s largest brownfield regeneration project, is unrecognisable. Some 3,500 homes have sprung up on a farm where the huge open pit mine once stood. The semi-detached houses sell for up to £300,000 each.

Most surprisingly, a nearby industrial estate dedicated to engineering excellence sits atop 80 meters of filled excavations. Some 150 companies employ 2,500 people there. There is also a training center which has equipped more than 2,000 apprentices in the last decade with vital manufacturing skills. Half came from the most deprived areas of South Yorkshire.

Rebuilt: The site of the Battle of Orgreave now houses a manufacturing research centre, with Rolls-Royce among its occupants.

“This was just a huge hole in the ground,” says Richard Scaife, regional development director at the University of Sheffield’s Advanced Manufacturing Research Center (AMRC), which oversees the complex of workshops, laboratories and design studios. The center was created in 2001 as an innovative collaboration between the local university and specialist technology and manufacturing partners to bring much-needed jobs and investment to the area.

The idea was simple: create a center that would bridge the gap between cutting-edge research conducted in campus laboratories and the practical, day-to-day needs of industrial production lines.

“At that time it was very unusual for academics to do that,” Scaife recalls. “It was very different from the normal way universities deal with business.”

This typically involved researchers submitting world-leading ideas and patents, only to develop them abroad. It’s what Scaife calls “a dead zone” where technology transfer from the lab to the factory fails. The funding gap left by angel investors, venture capital firms and risk-averse banks only made matters worse.

AMRC’s breakthrough deal came 20 years ago when it landed Boeing as a customer to test the center’s cutting tool technology.

It has since attracted significant investment and now counts among its clients Rolls-Royce, the UK Atomic Energy Authority, aerospace firm GKN and supercar maker McLaren, as well as Boeing and arch-rival Airbus.

The latest coup is to partner with a local company to help build aircraft in nearby Doncaster, creating 1,200 jobs. He has worked closely with Hybrid Air Vehicles since 2021 on research linked to its Airlander 10 program, providing expertise in areas such as low-emission propulsion.

“It’s a real boost to the region’s capacity and reputation,” says AMRC boss Steve Foxley.

The agreement with Boeing involves studying how to increase production of rear wings for the 737 aircraft.

“This university is developing full-size airplane parts (not to put on airplanes, because we are not a manufacturer), but we are testing scale manufacturing technology,” says Scaife.

‘We have done it in countless components. It’s foreign to the way a university would normally operate.’

So what’s the deal with Airbus, Boeing’s main competitor?

“The partnership allows us to do generic research,” Scaife says, noting that Airbus and Boeing share 70 percent of their supply chain. “An improvement in one part of that supply chain benefits both.”

The so-called “Chinese walls” are erected to prevent any competitive advantage from being obtained. It means that the AMRC only publishes research with the agreement of its commercial partners.

“A lot of care is taken to ensure confidentiality,” says Scaife.

The miners’ strike is often described as the moment when Britain – once the “workshop of the world” – gave up its rich industrial past and instead became a service economy focused on financial services and professionals. Another stereotype is that the closure of the mines caused communities to be permanently ruined.

Reality is more nuanced. The wells – which would now clash with environmental advocates – may have agreed with the tight-knit communities that surround them, but the manufacturing industry is alive and well.

It’s true that manufacturing accounts for less than a tenth of the economy after contracting during successive recessions, but it still accounts for 43 per cent of UK exports and employs 2.6 million people. Scaife points out that it also invests more in skills than any other industry and also spends more money on research and development.

In his latest Budget, Jeremy Hunt unveiled a £4.5bn package for the sector, including £975m for investment in energy-efficient, carbon-neutral aircraft equipment. The Chancellor also praised the fact that Britain is now the world’s eighth largest manufacturer, “recently overtaking France”.

The resilience of the manufacturing industry is impressive. In places like Sheffield – the old steel city – companies that have survived numerous recessions have adapted and learned to successfully apply high technology and automated precision to the machine tools they have been manufacturing for years. In doing so, they have also helped transform a former mining heartland in a way that few could have imagined in those dark days of 1984.

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them, we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.