A British rapper has opened up about living with paranoid schizophrenia and being “sectioned” for the first time.

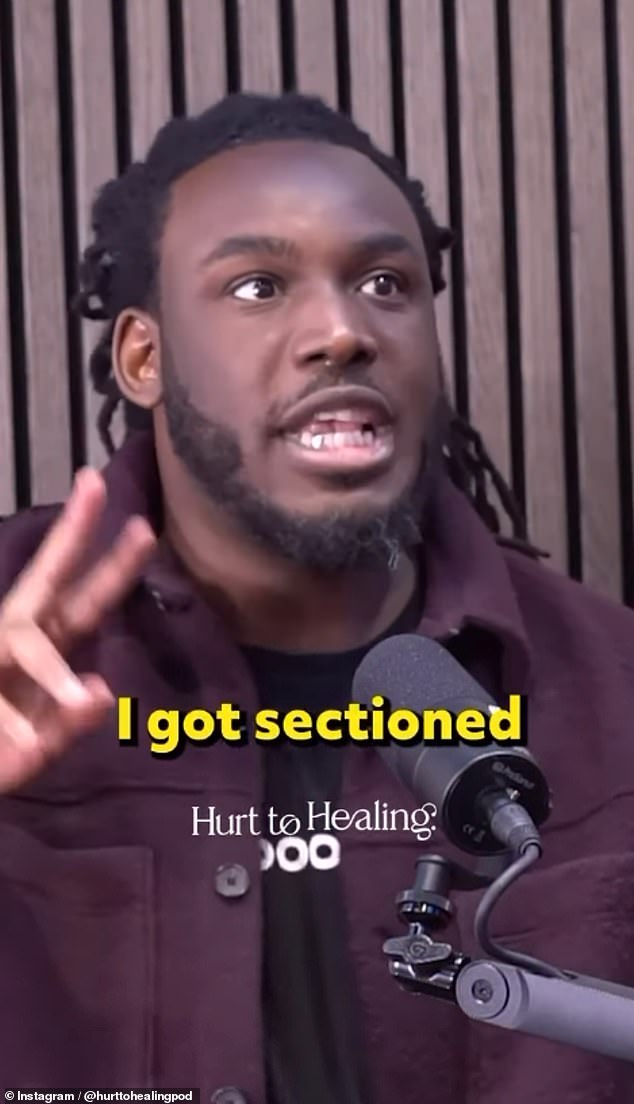

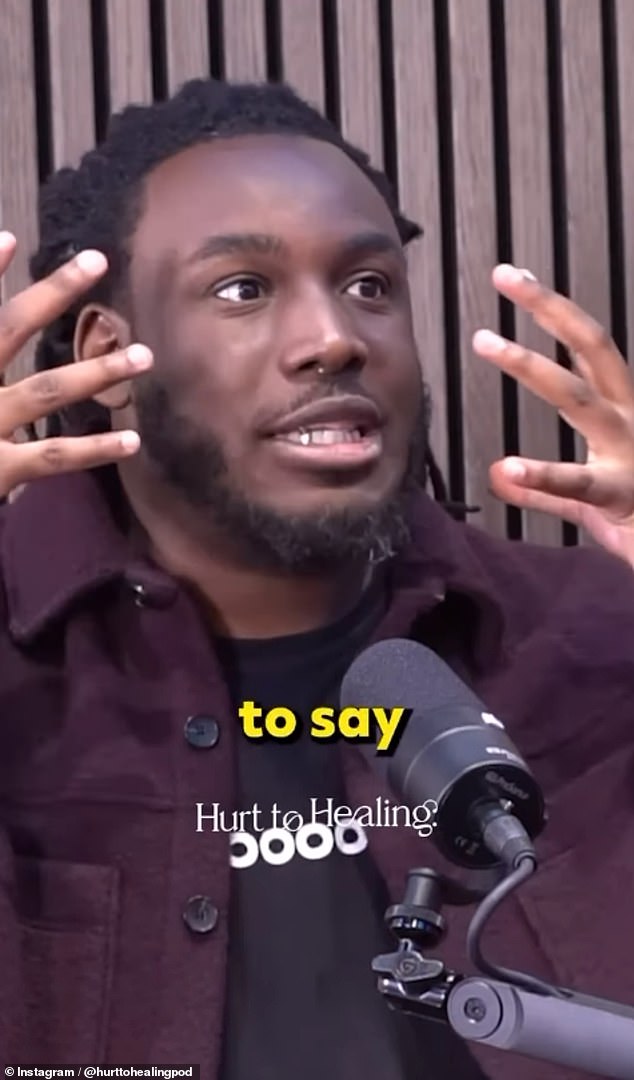

Grime rapper and mental health advocate Shocka, 35, from Tottenham, appeared on the Hurt to Healing podcast, where he spoke about struggling with mental health and manic depression.

In a fragment shared with instagramHe candidly recalled a time in 2011 when he “exploded,” prompting his mother to call a Nigerian pastor to “pray” the incident would go away.

An uncle who witnessed the episode believed that his nephew was suffering a ‘nervous breakdown’ and instead called the ambulance, which would hospitalize the rapper that same day.

In other videoThe rapper, whose real name is Kenneth Erhahon, said schizophrenia was one of the “scariest things” he had ever experienced.

Rapper Shocka spoke openly about living with paranoid schizophrenia and being ‘sectioned’ for the first time (pictured: Shocka on the Hurt to Healing podcast)

Recalling the first time he was admitted, which means staying in hospital under the Mental Health Act, he said: “It was 2011, it was December. I remember it because I was admitted twice in December…

‘I remember coming home and exploding. I don’t know what I was trying to say to my mom, but she was trying to say something but the words weren’t coming out.

‘My mom was realizing something was wrong. She knew something was wrong because we didn’t talk. So, to come to her and be like babbling things…’

The rapper, of Nigerian descent, spoke about mental health being a taboo topic in “African” culture. He then shared his mother’s reaction to the schizophrenic episode.

And I remember obviously the African culture: their first thought was “let me call a pastor.” Then he called a pastor from Nigeria and I remember him praying to me on the phone… I still felt the same way.

‘And then, luckily, I had an uncle who was a doctor. Then he came down the stairs, saw me and said, “Oh, your son is having a nervous breakdown, we have to call the ambulance.” They called the ambulance and that’s how they admitted me for the first time.’

The Grime rapper and mental health advocate, 35, from Tottenham, revealed that schizophrenia was one of the “scariest things” he has ever experienced.

The rapper appears here in 2010 before being sectioned for the first time. In the caption he recalls feeling “embarrassed” at the time, yet now sees the image as “evidence” of his “testimony.”

The Grime rapper, who wrote his first autobiography, A Section Of My Life, last year, also opened up about living with schizophrenia.

Speaking in a separate video, he said: “It’s one of the scariest things, of all of them, like anxiety, depression and bipolar disorder.”

‘When you’re going through that, like a schizophrenic episode, I can’t begin to explain it.

‘It’s as if I had tried to explain it in another interview. It’s like putting on virtual reality. [virtual reality] The glasses and virtual reality goggles you’ve put on are like all your worst fears.

But you are alone in that world. Everyone else who looks at you thinks “why is he being paranoid?” [about]? I can’t see what it is [seeing]. It’s like… it’s indescribable.’

Born Kenneth Erhahon, the rapper and influencer was born and raised in Broadwater Farm in Tottenham, north London.

The rapper, of Nigerian descent, spoke about mental health being a taboo topic in ‘African’ culture and recounted the moment his mother ‘prayed’ to a pastor for his condition.

Earlier this year, she took to Instagram to reveal that her father had passed away, while also sharing that she had recently lost her mother.

Shocka released his first mixtape Beast on the Loose in 2008, the success of which would later see him team up with fellow rappers Vertex and Double S to form the Grime collective, Marvell.

Two years later, the group was named BBC’s “Hot for 2010” alongside household names such as Tinie Tempah, Skepta and Chip.

However, the group’s success was short-lived and the sudden loss of Shocka’s once-promising music career would eventually lead to a decline in his mental health.

He returned to the scene years later with new music, but is perhaps best known today for his mental health advocacy.