A Nigerian man who scammed dozens of British and American women out of more than £50,000 has shared a step-by-step guide to manipulating women online, despite insisting he now lives a “good life” working for an agency. fraud prevention.

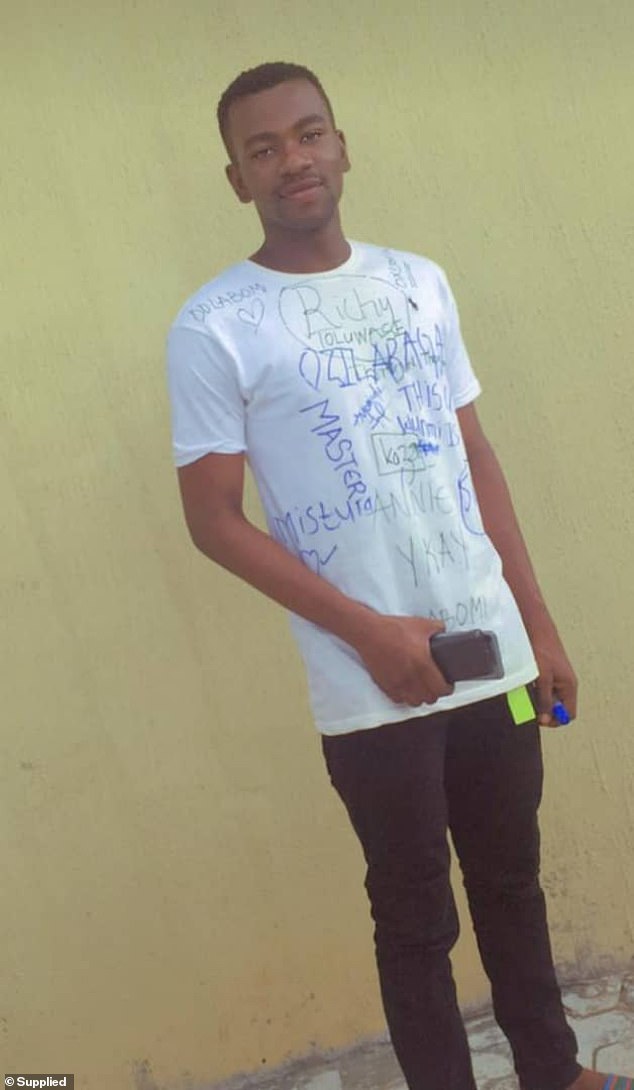

Christopher Smalling, 25, told how he spent six years lying to women to fleece them out of tens of thousands and stopped feeling guilty when he realized he could get rich.

“I used to feel bad, but as time went on and I started making a lot of money, a lot of money, I stopped feeling bad,” he told Sky News.

His ruthless scams led an elderly American to cough $20,000, which plunged her into a spiral of depression that destroyed her family.

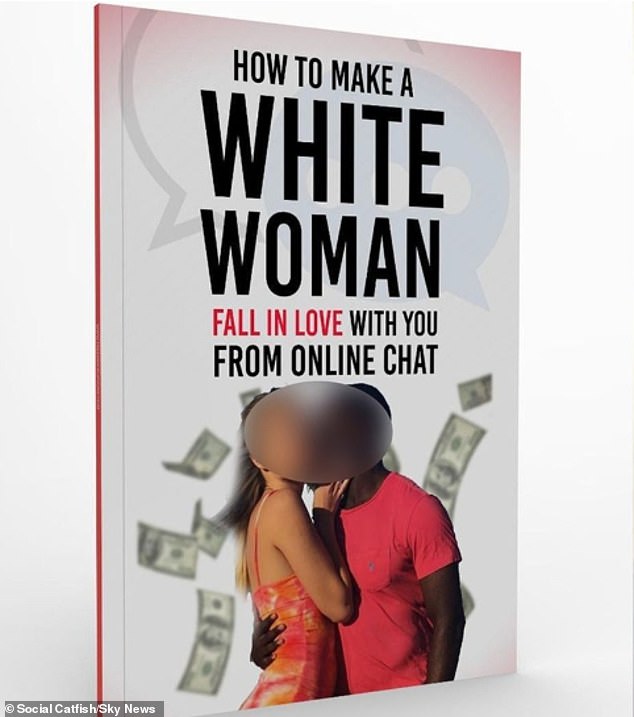

Now, Smalling has published a manual titled ‘How to Make a White Woman Fall in Love with You Through Online Chat’: A 40-page guide to malevolence and manipulation that he says are routinely used by Nigerian scammers to scam unsuspecting people out of their hard-earned money. hard to win.

The book, whose author is not named, pulls no punches and reads like a military campaign manual: cold, calculating and completely focused on the task at hand, describing victims as “targets” and instructing its users with ruthless efficiency.

Smalling has published a manual titled ‘How to Make a White Woman Fall in Love with You from Online Chat’, a 40-page guide to malevolence and manipulation that he says is commonly used by Nigerian scammers.

Maxwell says he scammed up to 30 women out of tens of thousands of pounds

The first line reads, “When it comes to chatting with white women, you have to understand that they are different from Nigerian women,” and then immediately instructs the reader to target vulnerable women over 40.

‘The guys who will fall in love with you ASAP without much stress. Choose people over 40: they are working, so they have the money you need.

“Also, being single at 40, they are eager for love,” he says.

The book quickly delves into great detail, providing a variety of scenarios and tactics that can be used to charm women with a complex web of lies from the first interaction.

It asks readers to conduct an analysis of all publicly available information about the “target,” identifying personal details, hobbies, interests, and important factors that can be leveraged to strike up a conversation.

And it provides an exhaustive list of pick-up lines, opening tactics, and jokes designed to make the scammer seem cheerful, charming, and genuinely interested, but not threatening.

Throughout, the guide instructs readers to write down any information they gain from their targets so they can later use it to manipulate them.

She also encourages the reader to intermittently ask the subject more questions and show as much curiosity as possible, because “(white women) love to talk about themselves.”

“If you let them talk about themselves, they’ll think you care and fall in love,” he says flatly, before providing a list of 60 compliments you can use in conversation at any time to keep the victim sweet.

Finally, the manual instructs readers to take their time and never ask for money directly.

Once a manipulator has gained the subject’s affection and trust, they are asked to drop hints about financial struggles or tell a heartbreaking story of how they themselves lost money.

By approaching the topic of money in this way, the book says, victims often offer money themselves without even needing to be asked.

Smalling says he was arrested in Nigeria when his scam was revealed, but was never prosecuted.

He also insists that he felt so bad after hearing that the American woman had become depressed that he came clean and the victim connected him to Social Catfish, a company that works to identify and expose scammers while educating people about the signs of warning.

Smalling now says he works with Social Catfish as a consultant, insisting that his experience with his American victim has changed his ways.

But he has never had to answer for his crimes nor has he returned money to his numerous victims.

Maxwell said he started scamming women when he was a teenager

As the manual used by Smalling mentions, older people are often more likely to fall for so-called “romance scams.”

Lloyds Bank revealed earlier this week in a warning ahead of Valentine’s Day that the number of people aged 55 to 64 who reported losing money to online dating criminals increased by 49 per cent in 2023.

Romance scams involve scammers luring their target into an online relationship and then extorting them for cash. Victims typically lost an average of £6,937 to scammers.

Banks say these types of fraudsters stole £31.3 million in 2022, but Action Fraud believes the real figure is closer to £95 million a year, as many victims are too embarrassed to report it.

Men were marginally more likely to fall for a romance scam, accounting for 52 percent of cases.

But women typically handed over more money – losing an average of £9,083 compared to £5,145 for men, Lloyds found.

Those aged between 65 and 74 earned the most money, with an average of £13,123.

Liz Ziegler, head of fraud prevention at Lloyds, said: “Targeting those looking for love is a cruel, but unfortunately common, way for fraudsters to profit. No good relationship starts by sending money to someone you don’t know.”

More than four in five people who were victims of a romance scam said they were deceived by the clever language used by criminals, the way they spoke to them, or the intimate conversations they had – exactly the tactics and materials described in the manual. shared. by Smalling.

These types of scams are by no means limited to dating apps.

Paul Davis, head of financial crime prevention at TSB, recently told the Home Affairs Committee: ‘We recently did some work in my team where we used our own personal Facebook profiles to engage with 100 sellers, 100 items, on Facebook Marketplace.

“Our assessment was that about a third of them were probably fraudulent.”

Davis said he had also recently seen a case involving a client in his 30s who had been the victim of a romance scam.

He said: “These are complex techniques that scammers use to convince people to do things they later deeply regret, and we see this as a common theme in many types of scams.”

“It is increasingly difficult for us to counter the methods these criminals use.”

Referring to the criminals, Mr Davis said that when speaking to victims: “It is clear that these are not lone actors, this is an organized fraud.”

‘Criminals specialize in different aspects of organized fraud and work together, similar to how a corporation or company would in the UK, to steal our cash.

“Clearly they operate all over the world and this is not something one person can do in their bedroom in the UK.”